Intelligence Report--Cadets At War: The True Story of Teenage Heroism at the Battle of New Market1/25/2017

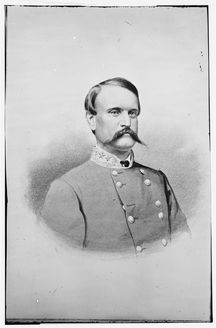

Earlier this week, I shared the story of the VMI Cadets' coming of age. On May 15, 1864, 257 cadets from the Virginia Military Institute ranging in age from 15 to 19 years old put their military training to the test. For many of these cadets, this was the first time in a live combat situation. They were supposed to be the reserve of the Confederate Army operating under General Breckinridge. After a Confederate regiment from Missouri was cut to pieces, General Breckinridge gave the order he dreaded: “Put the boys in, and may God forgive me for the order.”

This book from Susan Provost Beller looks at personal letters and cadet files in the VMI archives to give a voice to that small number of cadets who helped the Confederates turn the tide of the battle. Beller begins with providing a bit of background, takes us with the cadets as they march north (“down the valley”) toward New Market, advance around the Bushong Farm House and through a muddy field (the Field of Lost Shoes) and finally as they defend their honor in the press and public perception years after the guns have gone silent. The book is less than 100 pages long, so the background on the cadets and the battle is necessarily brief. The battle scenes have urgency and don’t get bogged down in lots of minutia. Beller’s use of the words and stories of only a few of the cadets gives the book focus. However, the maps are hand drawn and difficult to read. The illustrations, with the exception of the cadet photos, did not reproduce well. Both maps and illustrations fail to adequately support the text. The writing style is very casual; the author writes how I imagine she speaks. She mentioned in the introduction she has shared this story with school groups many times, and it sounds as if she simply provided a transcription of one of those presentations. It is probably beneficial for young readers, but for me, it lacked authority. One final thing that that is only incidental to the story but that bothers me enough to correct--or perhaps better explain--why going north through the Shenandoah Valley is actually “down the valley” while going south is “up the valley.” She gives a vague reason tied to Pennsylvania settlers moving south away from civilization and into the unknown, so they called it going “up the valley.” The real answer is much more concrete and even simpler: the Shenandoah River flows from south to north toward its confluence with the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry, WV. Therefore going south is going upriver—up the valley—and going north is going downriver—down the valley. It almost makes me call into question all of the research she did for this book. Thankfully, she quoted letters and official records enough that the voices of the cadets are authentic.

1 Comment

All they wanted was to be given the chance to show that the years they had spent training to be the next generation of Virginia’s military and political leaders hadn’t been wasted. What better way to prove their military training than during a real life, honest to goodness war? The cadets of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) believed their opportunity had finally presented itself. But over three years after the first shots of the Civil War, the 260 or so cadets of VMI—most aged 15 to 18 years old--had still not been called to fight for their cause. Certainly, the leaders in Richmond wanted to preserve the next generation of leaders from the dangers of combat; but they also needed their particular expertise in military discipline and drill. So the cadets had been called upon to train Virginia militia units before those units would take off to the front lines, leaving the boys behind. VMI, in the picturesque town of Lexington, was located along one of the most well-traveled and important valleys in all the Confederacy. The Shenandoah Valley runs along the Blue Ridge Mountains from southwest to northeast. The valley opens up near Harpers Ferry in what is now West Virginia, a mere 60 miles—or three days hard march—from Washington, DC and Baltimore. It was fertile farm land, had a good road running its length, and was a loaded gun pointed at important Northern cities. There had been extensive fighting throughout the Valley in 1862, when Union General Nathaniel Banks lost—as in couldn’t find—Stonewall Jackson and his army before Banks decided that the Confederate army outnumbered him (it did not) and that he was a sitting duck for destruction (only in his own mind) and abandoned the Valley. Given the importance of the Valley, it is remarkable that by 1864, the cadets of VMI were still looking for their first chance to “see the elephant.” In May of 1864, the new General in Chief of the Federal forces, US Grant, was ready to execute a grand strategic plan for every Union army fighting in the war. His plan for the spring campaign was a series of coordinated attacks on several of the Confederacy’s fronts, including the Shenandoah Valley.

On May 11, 1864, the Cadets received the news they had been waiting for: Headquarters Va. Mil. Institute May 11, 1864 General Orders No. 18 I.Under the orders of Maj. Gen'l John C. Breckinridge, Commd'g Dept of Western Virginia, the Corps of Cadets and a Section of Artillery will forthwith take up the line of march for Staunton, Va., under the command of Lieut. Col. Scott Shipp. The Cadets will carry with them two days rations. II.Captain J. C. Whitwell will accompany the expedition as Asst. Qr. Master and Commissary and will see that the proper transportation &c is supplied. III.Surgeon R. L. Madison and Asst. Surgeon Geo. Ross will accompany the expedition and attend to the care of the sick and wounded. IV.Col. Shipp on arriving at Staunton will report in person to Maj. Gen'l Breckinridge and await his further instructions. V.Captain T. M. Semmes is assigned to temporary duty on the Staff of the Commd'g Officer. By Command Maj. Gen'l F. H. Smith {Signed} J. H. Morrison, A. A. V. M. Inst. The boys were on their way to war. General Breckinridge only called forth the Cadets out of desperate necessity. He was uneasy about the prospect of actually allowing the Cadets to engage the enemy. “They are only children," he told an aide, "and I cannot expose them to such fire." It was his intention to keep the boys in reserve, hopefully protecting them from battle. But as the battle opened north of New Market, Virginia, on May 15, 1864, the Confederates were still significantly outnumbered. The 257 Cadets, while held behind the main line, were to play a pivotal role in the fighting around the Bushong family’s farm. The Union troops had taken position on a hill north of the Bushong farm house. The infantry was supported by artillery. It was a strong position, and the Cadets were marching toward it. As they marched up and over Shirley Hill, the Cadets came into artillery range. They were ordered to stop and discard their blankets and packs. Then they formed up in the third echelon, supporting veteran troops as they moved forward to attack. As the 51st Virginia Infantry and the 30th Virginia Infantry Batallion neared the area of the Bushong farm house, it came under withering fire and was cut to pieces, causing soldiers in the units to retreat in disorder and stalling the Confederate advance. There was now a dangerous gap in the grey line. Breckinridge gave the order. “Put the boys in…and may God forgive me for the order.” The Cadets moved into the Bushong orchard under heavy fire. Still, they advanced. They charged forward to the remains of a wooden fence and, laying down, opened fire for the first time. They were in this position only about 20 minutes when Confederate forces tuned the Union right flank on top of the hill and the artillery and infantry fire facing the Cadets slowed considerably. It was then the Cadets were ordered to charge. They rallied around their colors and rushed through a wheat field, and then through a recently plowed farm field that had been turned to mud by the previous days' rains. The mud was so thick it sucked the shoes from the boys’ feet. Even so, the Cadets were able to capture two Union artillery pieces and between 60-100 troops before the Federal forces retreated from the field. It may have been a time for gleeful celebration, but the Cadets had come on to the field 257 strong. During the battle five Cadets had been killed in action, and another five would die from wounds they sustained during the fight. 45 other Cadets were wounded, though not mortally. The battle was a Confederate victory that tuned back the Union advance. General Sigel was soon replaced by David Hunter who would advance back up the Valley and in June, burn down the campus of VMI. The Field of Lost Shoes holds a special place in VMI history. Every year, first year Cadets, known as Rats, visit the New Market battlefield and charge across the Field of Lost Shoes before they officially take their oath of Cadetship. The Field also evokes a powerful image of lost youth. Much like the empty boots in the stirrups of a riderless horse, the idea of empty shoes being pulled out of a muddy morass conjures images of boys charging forward into battle, lost forever to the innocence of childhood--or lost even to life itself. Cadets Killed at the Battle of New Market

Earlier this week, I shared with you the story of Johnny Clem. The nine-year old earned fame for things he did and things he probably didn’t do. Called both “Johnny Shiloh” and “The Drummer Boy of Chickamauga”, Johnny survived the Civil War and later in his life went on to have a second distinguished career in the United States Army

Johnny’s story is the subject of John Lincoln Clem: Civil War Drummer Boy. This is a work of historical fiction and author E.F. Abbott has done a wonderful job creating an engaging, book-length story for young readers. The main character, Johnny Clem himself, is a well-written multidimensional character. He is stubborn and defiant, but honorable. He has a moment of cowardice and resolves to be brave. He is good but flawed. He is someone you want to root for. The author weaves in a lot of vignettes about camp life for ordinary soldiers including the rampant disease that would claim more lives than bullets did. She even uses a well documented description of General Grant-- “He wore an expression as if he had decided to drive his head through a brick wall and was about to do it.” The battle scenes are realistic and urgent and don’t romanticize what was truly a confused and terrifying experience. As a piece of fiction, this book is top notch. Unfortunately, the author’s research on her subject seems spotty. As I noted in my previous post, it is highly unlikely that Johnny was ever at Shiloh. The 3rd Ohio, the regiment he unofficially joined in this book did not fight at Shiloh and the 22nd Michigan, the regiment that he eventually formally enlisted with, was not mustered in until August 1862, several months after the battle of Shiloh. Several times, the author refers to beating the long roll as a call to advance. The long roll was actually a call used to call the soldiers to arms. It was to get the troops’ attention and get them all in one place so that a subsequent order could be sounded. It was not beat throughout an advance or to announce a charge. An additional concern appears when Captain McDougal asks the assembled crowd the reason the Confederate states seceded. The crowd answers “slavery” and McDougal adds a whole bunch of other things that are another way of saying slavery including economics and states’ rights and throws in the tariff for good measure. Captain McDougal tries to lessen the impact slavery had on the Confederacy’s founding, which does a disservice to the actual history. To add insult to injury, officers of the rank Captain are in command of a company of approximately 100 soldiers, not entire regiments (until later in the war when casualties began to mount). Regiments were commanded by Colonels. Because of the strong fictional narrative, I still highly recommend this book despite the historical liberties taken. In fact, the inaccuracies provide an opportunity to research some primary documents in a critical manner.

John Lincoln Clem: Civil War Drummer Boy is a great way to introduce the role of children in combat with an engaging and fast moving story so long as it is understood to be historical fiction.

Johnny was with the regiment when it engaged the Confederate army on the afternoon of September 20, 1863 along a creek in north Georgia called Chickamauga. On that day, Johnny shed his drum and instead carried a rifle musket, trimmed down from regulation length to fit his short stature. The battle was chaotic and the 22nd Michigan was being surrounded when a Confederate Colonel noticed the child soldier with his shortened weapon. The Colonel demanded that Johnny surrender by saying “I think the best thing a mite of a chap like you can do is drop that gun”. Johnny disagreed. In his opinion, the best thing he could do was to use it. He refused to surrender and instead shot the Colonel and headed back to his unit. Johnny, who at some point during the war officially changed his name to John Lincoln Clem to honor the President, was rewarded for his bravery under fire with a promotion to sergeant, becoming the youngest non-commissioned officer in the history of the United States Army. And the American public granted him another laurel wreath, deeming him “The Drummer Boy of Chickamauga.” The harrowing times were not over for Johnny. In October of 1863, he was detailed as a train guard when Confederate cavalry captured him. He was take prisoner and had taken from him his Union uniform, including his prized hat which sported three bullet holes it had received at Chickamauga. He was released in a prisoner exchange not long after, and would go on to fight in other battles as the armies marched toward Atlanta. John Clem was officially discharged a year after his harrowing experience at Chickamauga in September 1864. But John Lincoln Clem was not done with the army. After graduating high school in 1870, he tried--and failed--to pass the entrance exam for the West Point Military Academy. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him second lieutenant in the 24th US Infantry and over the years, he steadily moved up the ranks and upon retirement was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General. In honor of his service, upon his death in 1937, he was buried in Arlington Cemetery,

Even without the feats ascribed to "Johnny Shiloh", the events that young Johnny Clem experienced before he turned 14 make his life a fascinating story that shows that often, children are capable of more than we could ever give them credit for.

References and Further Reading John Clem, Drummer Boy of Chickamauga The Boys of War The Drummer Boy of Shiloh by WS Hays 15 year old Union soldier Sheldon “Say” Curtis meets Pinkus “Pink” Aylee while Say is suffering from a leg wound. Pink and Say have both been separated from their units, and they make the decision to travel the three days they anticipate it will take to rejoin their units. Along the way, they return to Pink’s home and recover under the care of his mother Moe Moe Bay. The setting, a cozy cabin on the ruined estate of Pink and Moe Moe Bay’s former owner, creates an evocative backdrop for meaningful discussions about fear and bravery, the true nature of freedom and sacrifice.

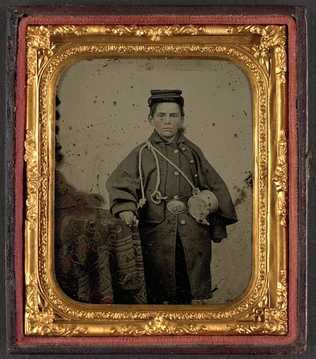

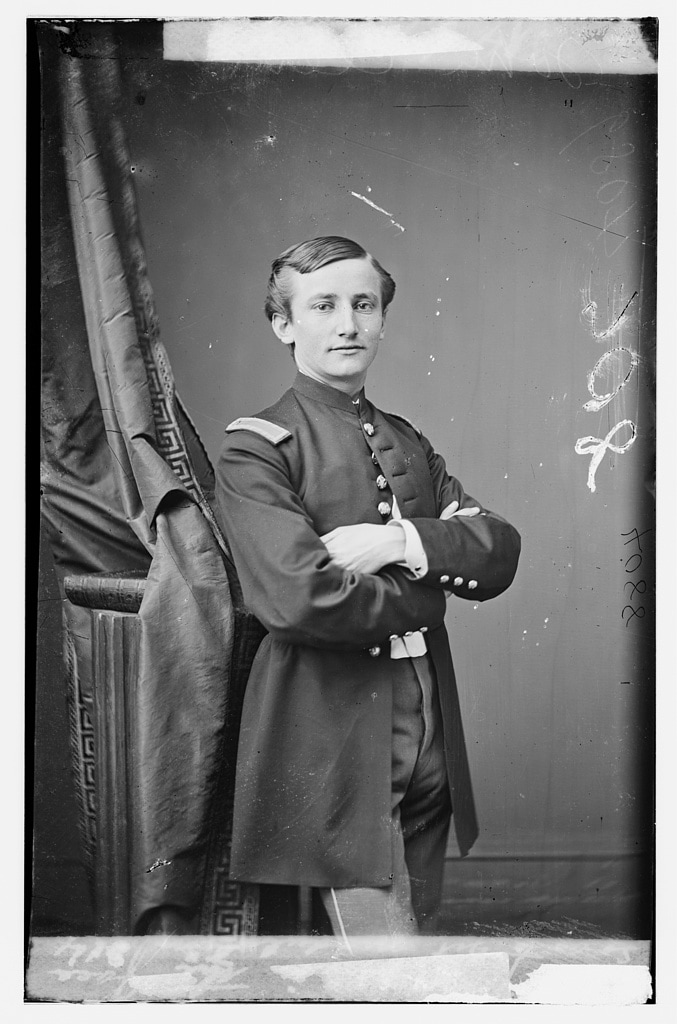

In 48 short pages, Polacco writes a story with developed characters who discuss the deeper impact of the war, and challenge us readers to think about some of its enduring themes. There are many topics for family or classroom discussion. Despite giving this book 5 stars, I do have a few concerns. The first, and probably most problematic, is the audience for this book. It is a picture book, but the topics discussed and the graphic nature of the illustrations, skew this older than the typical picture book audience of preschoolers to young elementary readers/listeners. Two of the most moving vignettes captured in the story are deaths--the first that of Moe Moe Bay at the hands of “marauders” who come looking to loot Pink’s family cabin, and then Pink’s death himself by hanging at Andersonville. These topics are important to understanding the Civil War, and I do not advocate shying away from the difficult discussions. Knowing the true toll of war brings it from the realm of romanticism into reality. As Robert E. Lee said “It is good that war is so terrible--lest we grow too fond of it.” I do struggle, however, about the age appropriateness of this material. Amazon lists the appropriate age for this alternatively as: age 5-9; ages 6-9; Grade 4 (age 10) and up and Grade 1 (age 7) to Grade 4 (age 10). My best advice is for parents and teachers to read the book first to determine if your children or students are ready to handle the weighty discussions which will likely result from this book. My final reservation is that the author claims this is a true story handed down through family history. This simply is not the case. A review of the regimental muster rolls for the 24th Ohio Volunteer Infantry (Say’s regiment) does not show any soldier enlisted by the name of Sheldon Curtis (or alternative names that could have been the result of administrative error). Pinkus Aylee does not appear in the muster rolls of the 48th United States Colored Infantry. Further confirming the fictional nature of the story, according to each unit’s history, these two units never fought in the same battles. The story is strong enough to stand on its own without the disclaimer that this is a true story handed down generation by generation. It is possible the author deliberately used this “true story” label disingenuously. It is equally possible that the author, like so many of us, just accepted family history as gospel truth because it came from the sincerest of her elders. Either way, the fact that it is fiction from someone’s imagination does not diminish its impact. Even knowing the truth, I end the story with tears in my eyes as I say out loud, “Pinkus Aylee.”  Union Drummer Johnny Jacobs; Library of Congress Union Drummer Johnny Jacobs; Library of Congress We typically think of war as the work of adults. Adults make the policies that lead to war. Children should not be exposed to the death, destruction and moral ambiguity that results from armed conflicts. Today, all branches of the American military require enlistees to be at least 17 years of age (with parental consent). But war hasn’t always been something that society has tried to shield children from. The Civil War has often been called The Boys’ War because of the young ages of the combatants. The average age of the Union soldier was 25.8 years (records for the Confederate armies are incomplete making it difficult to figure an average age). Both armies had policies that required a minimum age of 18 to enlist*, but that was policy, not necessarily practice. A determined young man or an unscrupulous recruiting officer could find ways to circumvent these rules, and they did so with alarming frequency. Many of these children were initially enlisted as musicians, but when the fighting started, either by choice or circumstances they found themselves carrying a musket or picking up a ramrod. The deadly hail of lead made no distinction of age when it found its target.

*The Union Army’s minimum enlistment age was 18, and 17 for musicians. Younger children could enlist with parental permission. For the majority of the Confederacy’s existence, the minimum enlistment age was 18, but in 1864 that was lowered to 17. Sources and Further Reading Child Soldiers in the Civil War Children in the Civil War The Boy's War: Confederate and Union Soldiers Talk About the Civil War by Jim Murphy |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed