I don’t usually read two books at one time, but as the departure date of our Charleston vacation quickly approached, I had to make an exception. I haven’t known the remarkable story of the Hunley for long, but I knew it was woven into the fabric of its adopted home town of Charleston and made visiting it a top priority. Like pretty much every other historical site I visit, I like to prepare with a little homework to help me understand what it was I was going to see. I had two books I wanted to read--one focusing on the history of the submarine and the other focusing on the modern search and recovery--and only time to read one.

Between trying to clear my desk of urgent work for my day job, keeping up with Drummer Boy and the general running of the household, I could only dedicate half an hour or so during the evening, some days per week to reading. The only other time I had to dedicate to reading was my commute. But even as a passenger, reading while in a car would not translate to a particularly good time for me or anyone in my general proximity. As a solo driver with over an hour commute each way several days a week, reading while driving is not...encouraged. Thank goodness for Audible, the only safe way to read while driving (unless, I suppose you have hired a professional narrator that travels with you every where you go). I listened to Tom Chaffin's book on my way to and from work and work appointments and read Hicks and Kropf's book while curled up into the corner of my couch after Drummer Boy finally agreed to close his eyes. Reading both at virtually the same time allowed me to compare and contrast the two books much more easily as most of the information remained fresh in my mind while the authors crafted their own explanations and tried to use their sources to back their positions. It was an unwitting debate between the authors, and I got to judge the best position. The H.L. Hunley: The Secret Hope of the Confederacy was primarily focused on the history of submarine development, putting the Confederate efforts--including the CSS Pioneer and the American Diver--in historical context. Chaffin also used his time to illuminate the back story of the men who would propel the technology forward. Two-thirds of his book focused on the time leading up to the sinking of the Hunley, and only the final third focused on the aftermath. Ultimately, Chaffin only dedicated the final three chapters to the search for, and recovery of, the Hunley. Raising the Hunley: The Remarkable History and Recovery of the Lost Confederate Submarine by Brian Hicks and Schuyler Kropf is a story mainly of the efforts to find and then recover the Hunley. There is a discussion about the history of the submarine and its predecessors, but only the first third of the book covers this, leaving the authors, local Charleston journalists who were eye witnesses to the recovery and early conservation of the craft, lots of time to tell you exactly what they saw. So, which book should you read? Readability In The H.L. Hunley, there are several times Tom Chaffin uses $5 words when nickel words would do. Some of those times actually caused me to roll my eyes, their use was so out of place (dare I say egregious) within the structure of the sentence they were used in, it seemed an obvious effort to show off a superior vocabulary just because he could. While most of his text is highly readable, it is likely that you will learn a few new words to add to into your not-so-everyday conversations. Raising the Hunley is written by journalists and the reading level reflects this. Hicks and Kropf do not dumb things down, but they keep the language easy and the reading flows well. It is descriptive but not challenging. Winner: Raising the Hunley Credibility of the Authors Tom Chaffin uses his introduction to explain his method of historic research. He focuses on using primary documents and when he cannot document, he clearly identifies his own use of speculation. One of the best ways to see his extensive use of historic record is how he debunks the widely accepted myth that Queenie Bennett both gave George Dixon his famous gold coin and that she was his sweetheart. Hicks and Kropf’s eyewitness status to the raising and recovery of the Hunley notwithstanding, their sourcing is generally secondary documents (documents written by people who were not participants or contemporaries of those participants living at the time). Winner: The H.L. Hunley Overall Quality of the Work Chaffin’s book was published in 2008. It is a careful and thoughtful treatment of the history of the Hunley. His sources are credible, and he carefully discloses the rare instances of author speculation. Though there are some sections that are a bit dry and more academic, it isn’t something that plagues the whole of the book. Published in 2002, Hicks' and Kropf’s book reads like they rushed to write and publish it to take advantage of a transient public interest that would soon fade. Besides their unquestioning adherence to the Queenie Bennett myth, they also retell the story of the blue light from the lantern that was the prearranged sign to alert the crew’s home base on Sullivan Island that they had been successful, going so far as to cite the archaeologists’ find of the submarine’s lantern still inside the submarine as proof. They leave out, however, that the lantern’s lenses were clear and that there is no indication that they were ever tinted blue. Had they waited for more of the excavation of submarine, and allowed the findings to drive their narrative, rather than the other way around, the book would have improved greatly. Winner: The H.L. Hunley These are not the only books available on the Hunley, and I picked up several others while I was at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, including a newer work by Brian Hicks published in 2014 which may correct some of the errors of his prior work. But until my schedule and reading list allow, people who wish to learn more about the sad tale of the remarkable men and their submarine won’t go wrong picking up or listening to Tom Chaffin’s The H.L. Hunley: The Secret Hope of the Confederacy.

0 Comments

An equally important naval technology was developed by private Confederate citizens, leant to the Confederate army and succeed where others before it had failed. And yet, many people have never heard the name of the H.L. Hunley.

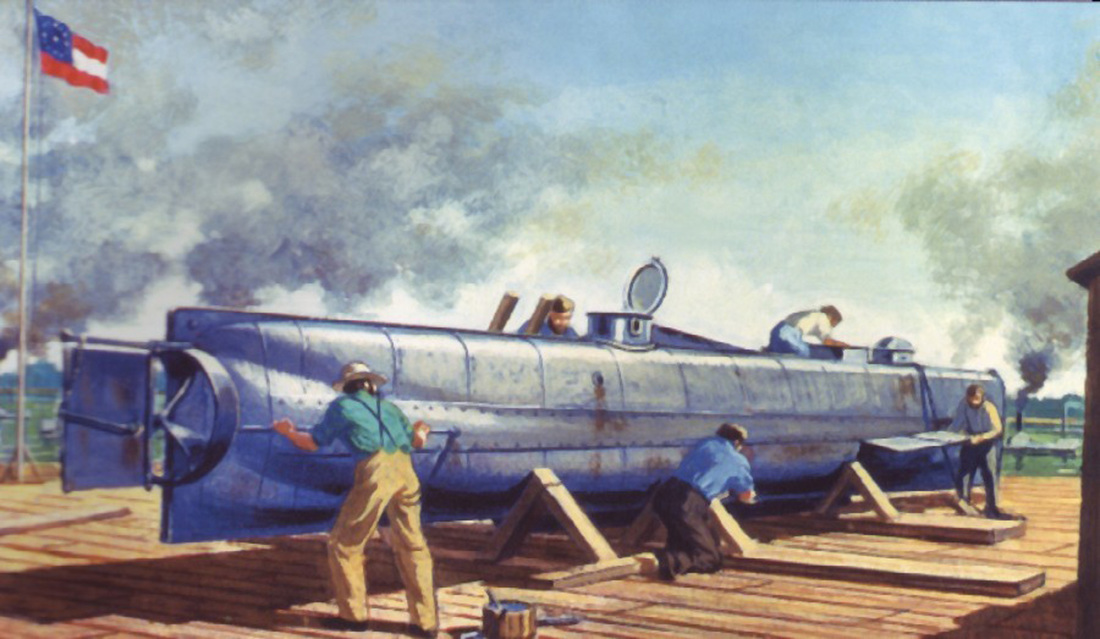

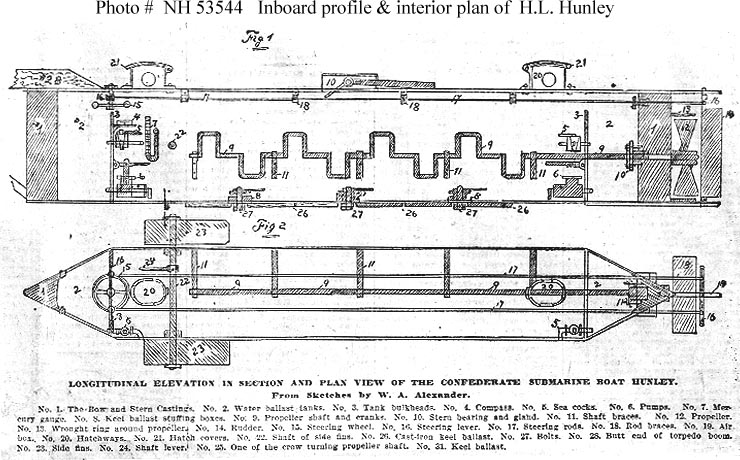

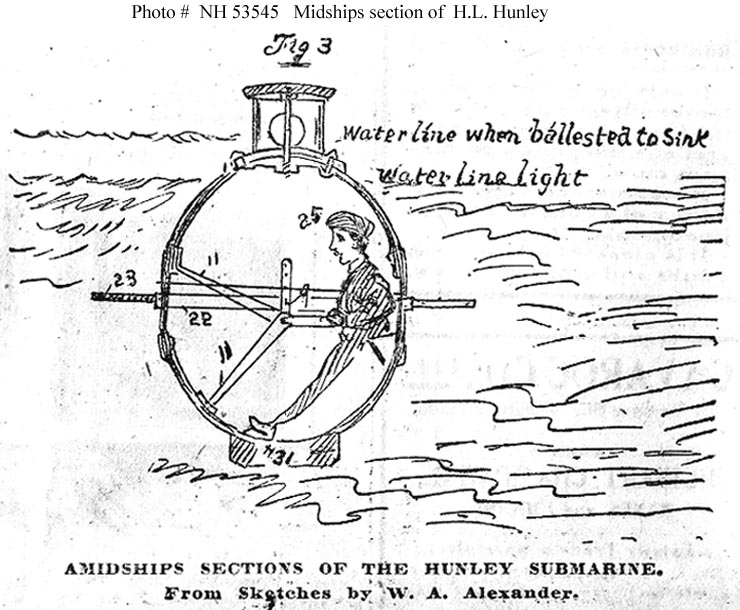

In fact, the Hunley started out its life with the moniker “the fish boat”--an adequate description of what it was: a cigar shaped boat designed to be completely submerged. It was a submarine. The fish boat was 39.5 feet long, 4 feet tall and only 3.83 feet at its widest. The eight crew members entered through one of two oval hatches that were only 14 inches by 16 inches. While they were inside, the captain stood with his head in the front conning tower navigating and working the lever that moved the rudder, and the rest of the crew sat shoulder to shoulder on a narrow wooden bench that extended along the side of the curved wall and bent over a series of connected hand cranks that ran the length of the fish boat. These seven men were the motive power of the boat.

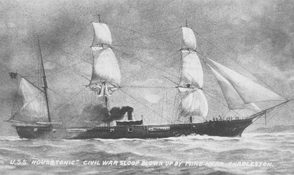

The ship was built in Mobile, Alabama and its original owners Horace Lawson Hunley, James McClintock and Baxter Watson, originally had visions of their fish boat as a privateering ship--a privately owned vessel with authorization from the Confederate government to capture or sink enemy ships for a bounty. They wanted to make money. General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, the Confederate general in charge of the defenses of Charleston, South Carolina, had other ideas. He requested the fish boat’s presence in Charleston. The harbor was being blockaded by the Union fleet. Blockade running ships were fewer and further between and Charleston--the entire Confederacy, in fact--were being choked off from world commerce. Beauregard loved audacious plans. What could be more audacious than using a secret fish boat to blow up Union vessels to destroy the blockade? The boat was transported to Charleston via rail and once it arrived, the crew of eight began sea trials to learn how the boat worked. Only two weeks after the move, the fish boat sank as water entered its open hatches as it was leaving port. Only three of its crew survived. The boat was raised by divers in hard helmets and diving suits, cleaned and returned to service. This time, the handpicked crew would be led by Horace Hunley himself and he officially christened the submarine the H.L. Hunley. He was sure that the first sinking was caused because of the incompetence of the crew and commander who were unfamiliar with the submarine. In October 1863, during a training dive, the Hunley passed beneath the CSS Indian Chief and didn’t come back up. Somehow the crew left open one of the valves that let water into the ballast tank and the boat flooded. All eight men on board died. One of those men was Horace Hunley. The boat was raised again but Beauregard was ready to call it quits. “It is more dangerous to those who use it than the enemy.” Lieutenant George Dixon knew the Hunley. He had been working on it since his regiment, the 21st Alabama, had been reorganized and sent to Mobile for the defense of the city. He had survived a wound to the leg at Shiloh possibly only because the minie ball struck a $20 gold piece that had been in his pocket. He was supposed to have been on the Hunley’s second crew, but had been called back by his unit only days before the fateful training run that ended the lives of all eight crew members. He was lucky. And he knew the Hunley better than anyone else. Dixon convinced Beauregard to let him have one more shot at making the Hunley successful. He was persuasive, and Beauregard got him released from his unit to captain the Hunley. Dixon lead seven other men, all volunteers who knew the boat’s sad history, in training runs based from a dock on Sullivans Island. Finally, the weather cooperated, the crew was ready and Dixon had his target in sight. At about 7:00 pm on February 17, 1864, Dixon and his crew set off toward the large wooden sloop USS Housatonic. His plan was to ram the torpedo which was at the end of a spar that extended from the bow of the ship into the side of the Housatonic, then back away to a safe distance before detonation. They would then show a blue light and the men on shore would answer by lighting a bonfire to guide them back home. At about 8:45 pm, men standing watch on the deck of the Housatonic spotted something that looked like a submerged log moving slowly toward them. They reacted quickly, but the log continued on its approach.

With the sinking of the Housatonic, the Hunley became the first submarine in world history to sink an enemy ship in combat.

But the Hunley never returned. The wreck was found in 1995 and raised in 2000. The remains of all eight crewmen were removed from the wreck and laid to rest in Magnolia Cemetery with the other Hunley crew members who had perished as members of the submarine's first two crews. The submarine is undergoing conservation efforts at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center in North Charleston, South Carolina and the public can see the historic sub on the weekends. Even now, 16 years after the raising of the H.L. Hunley and extensive conservation efforts, it is unclear what happened to the submarine and its third crew. The crew of the Housatonic used small arms to fire on the Hunley as it approached. Did the hail of lead damage the Hunley? Was it damaged by the same torpedo blast that opened the Housatonic’s hull? Did they get turned around and unintentionally head out to the open ocean? Did they simply run out of strength to travel the 5 miles back to their friendly port and drift away exhausted? Or did they simply run out of air? Despite the lingering questions, the H.L. Hunley's place as the first submarine to sink an enemy ship in combat is secure. But one does wonder...can a mission be successful when the crew simply vanishes? Bibliography Raising the Hunley: The Remarkable History and Recovery of the Lost Confederate Submarine by Brian Hicks and Schuyler Kropf The H.L. Hunley: The Secret Hope of the Confederacy by Tom Chaffin Friends of the Hunley Resources

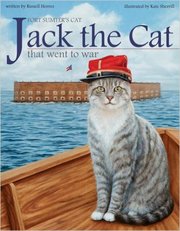

Drummer Boy is looking forward to his vacation in Charleston, South Carolina next month. I like reading ahead when I visit a battlefield or historic site. It helps me better appreciate where I am visiting. It also helps ratchet up the anticipation for an upcoming visit. So, I went looking for a book to read to Drummer Boy that introduces Charleston’s Civil War history in a way that is entertaining for a 4 year old. That is when I made the acquaintance of a “most unusual cat.”

Jack, the son of Miss Kitty and Mr. Tom, lives with the Rhett family in Charleston. He witnesses the initial bombardment of Fort Sumter before Colonel Rhett decides to take this self-proclaimed Confederate cat to the fort itself to help the soldiers control the mice eating their food stores and the birds polluting their drinking water. Readers learn about the layout of the fort, its Confederate occupation, bombardment by Union naval forces, and the lives of the Confederates inside the fort’s walls. Jack’s story is based on oral tradition and period illustrations that indicate that a garrison cat existed at Fort Sumter. The book also contains actual documented historic events and figures who were important to the city and fort’s history. It is an effective blending of fantasy and fact to create a memorable story. One of the big challenges with all children’s Civil War books--especially picture books-- is presenting the information in a way that honors the history in an age appropriate way without sugarcoating it. Many books like this struggle integrating slavery and the reality of the antebellum South in a way that doesn’t minimize the former and glorify the latter. Russell Horres strikes the right balance as he spends all of one page describing Jack’s antebellum life, accompanied by Kate Sherrill’s beautiful misty depiction of hoop skirts, oak tree avenues and a columned Great House. But he also introduces Mauma June, a slave who describes her abduction from her family in Africa, her sense of loss and the limits to her freedom. In a particularly telling moment, she admits to Jack that she is envious of him—the family pet—because of his freedom. The book is text heavy, but each page is accompanied by beautiful illustrations that bring Jack to life, help illustrate the charm of Charleston and highlight the insular world of life in such a small, isolated fort. The final pages provide an illustrated Glossary of Terms that helps both the children and any adults reading to them build their vocabulary. This book was written in 2011 for the sesquicentennial (150th anniversary) of the first shorts of the Civil War. It is no longer in print, but new and used copies are available through Amazon's third party sellers and other used book vendors. Click on the book's title in this post to see the new and used offers on Amazon. Intelligence Report--Allegiance: Fort Sumter, Charleston and the Beginning of the Civil War8/6/2016

The first shots of the Civil War were fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 12, 1861. It was the beginning of a war, the scope of which was beyond the general citizenry’s imagination. This wasn’t only a beginning, but the ending of months of political and diplomatic failures that highlighted just how unprepared everyone was for the fight about to commence.

David Detzer’s Allegiance: Fort Sumter, Charleston and the Beginning of the Civil War examines both the beginnings and endings that took place in and around Charleston during the Secession Winter of 1860 and the following spring that resulted in the fateful cannon shot that started the war. Our cast of “characters” include:

It takes a special author to create suspense and a sense of urgency in a story of which we know the ending. Detzer does this. Even though we know that the Confederates fire on Fort Sumter, as we watch the calendar pages turn, the deft maneuvering by Union Major Robert Anderson, and the desperate incompetence of President Buchanan produce moments of frustration and disbelief for the reader. Detzer paints Anderson as a man who is trying his best and being misunderstood at every turn. It doesn’t help that he has little to no political or military support aside from vague orders and non-specific encouragement. Further complicating issues is the fact that South Carolina is determined to see Anderson’s actions as coercion intended to force a military engagement despite the actions being taken deliberately intended to deescalate tensions to the extent his vague orders allowed. There were so many times in the months between South Carolina’s declaration of secession and the bombardment of Sumter that could have initiated war (firing on of the Star of the West and the clumsy and comical efforts of the captain of the ship Shannon) that the ending seemed inevitable. We are only left wondering exactly when the fuse would burn up and the powder keg blow. It is important to note that only the final two chapters deal with the actual bombardment of Fort Sumter. It is a compelling part of the story, but it is the easiest and most straightforward part. The bulk of this book is about politics and diplomacy and the failures and success of each, which makes this more of a political thriller than a military history. This book is a great introduction into the messy politics of revolt, revolution and the start of a civil war. It reads like a novel, with well drawn characters you will care about. A great book for mature readers interested in how this kind of conflict starts, and those who love a good novel of political intrigue. |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed