Sarah Emma Edmonds Sarah Emma Edmonds When you think of a Civil War soldier, what image comes to mind? Perhaps a young man, thin and haggard, wearing tattered butternut. Maybe a middle aged African American soldier wearing blue for the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Maybe you think about a little boy, wearing a drum across his small body or a bugle over his shoulder. No matter what image pops into your mind, chances are the soldier you are picturing is male. According to the Civil War Trust, over 3 million soldiers fought during the Civil War and the vast majority of those soldiers were men as neither the Union nor Confederate army had a policy allowing the enlistment of female soldiers. But as many as 400 women fought regardless, serving in Union and Confederate uniforms during the war. One of those dressed in Union blue, Sarah Emma Edmonds, left behind a memoir detailing her history, and though historians are skeptical of some of her claims, what is verified fact about her life shows a woman not content to sit on the sidelines while her adopted country fought its defining war. Sarah Emma Edmonds was an American by choice. She was born in the province of Nova Scotia, Canada in December in 1841. Her father was disappointed she was not a boy, and she spent much of her young life trying to prove to him her worth. Eventually, seeing the futility of her efforts, she fled from her father’s oppression and an arranged marriage, first to New Brunswick, and later, to put more distance between herself and her father, she immigrated to the United States. She did so in disguise, adopting the persona of a young man named Franklin Thompson. She had established herself as a traveling Bible and bookseller, first in Connecticut, and later outside of Flint, Michigan where she was living when the Confederates opened fire on Fort Sumter and President Lincoln issued his call for 75,000 troops to suppress the rebellion. Edmonds decided it was time to fight for her new country.

She disguised herself as black male “contraband” named “Cuff” performing manual labor for the Confederate army.

She drew on her experience as a traveling book seller to pose as an Irish peddler woman named “Bridget O’Shea” selling goods to Confederate soldiers behind enemy lines. She donned black face and a red bandanna and while working as a washer woman, came across a packet of official papers that had been in a Confederate officers’ uniform jacket. Her unit was transferred several times, and it eventually ended up in the western theater, where Edmonds continued her work as a spy, and then as a nurse. It was here, while she was tending wounded and ill soldiers, that she contracted malaria in 1863. Afraid her secret would be discovered if she were treated by the army surgeons, she requested a furlough. When it was denied, she left her unit for treatment. Franklin Thompson was declared a deserter and Edmonds’ military career was at an end. Even while the war still raged, she wrote her memoirs titled Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, the first edition of which was published in 1864. She donated the money she earned from book sales to various soldiers’ causes. When the 2nd Michigan held a reunion in 1876, her former comrades in arms welcomed her warmly and took up the cause of removing the blight of “desertion” from Franklin Thompson’s military record, which led to Edmonds being able to receive a military pension in 1884. In 1897, she joined the Grand Army of the Republic, the fraternal organization of Union Civil War veterans. She was the only woman ever to do so. After the war, Edmonds married and had three children. She moved to Texas with her family and died in 1898. She was buried with military honors in Washington Cemetery in Houston. References and Further Reading Sarah Emma Edmonds, Private Sarah Emma Edmonds Biography Memoirs of a Soldier, Nurse and Spy: A Woman’s Adventure in the Union Army by Sarah Emma Edmonds

0 Comments

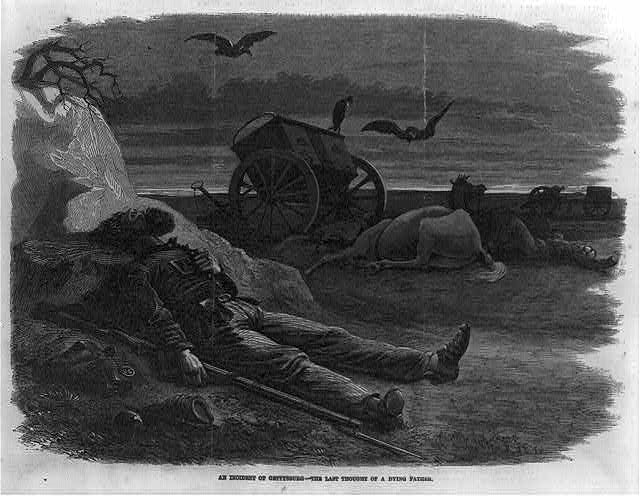

Amos Humiston, Photographer Unknown Amos Humiston, Photographer Unknown This time last year, social media was on the hunt for a man who was photographed dancing at a club. The caption of the photo posted on an internet message board indicated the overweight man had been ridiculed by his fellow club-goers and was embarrassed into stopping. It wasn’t long before the post went viral and the man, a Brit named Sean O’Brien, was identified and invited to a Hollywood dance party organized just for him. The incident showed the power of social media, the ability of a vast network of barely related people to search the globe to find people and bring them together. Sometimes it is hard to remember that this technology is still, in the grand scheme of things, very new. 150 years ago, as the Civil War raged across the country, no one could even imagine the capabilities we have today. Today, anonymity can be difficult. In 1863, it was a possibility that was all too real to the men who fought. In the midst of the Civil War, communication was still relatively primitive. No one was going to be able to post a photo of an anonymous soldier and broadcast it around the world seeking his identity. Because dog tags hadn’t been invented yet and most soldiers hadn’t gotten into the habit of pinning their names and units to their uniforms, many men faced the possibility that their final words and last breath would happen in anonymity, and their bodies would be committed to a final resting place without a name on their headstone. It may have been this fear that ran through Amos Humiston’s mind as he lie dying in a remote portion of the Gettysburg battlefield on July 1, 1863. He had been part of the 154th New York, and his regiment had been positioned on the northeast side of town as the battle commenced. As the Confederates bore down on the town, the 154th New York was overwhelmed and as their line gave way, the soldiers put up a fighting retreat through the streets. The firefight was intense and Amos Humiston was mortally wounded. We cannot know how long he suffered, but we do know that his death was not instantaneous. How? Later in the week, his body was found near the corner of York and Stratton Streets, with an ambrotype of his three children clutched in his hand. That ambrotype was the only identification on him. His unit suffered heavy casualties from the fight and those who survived had already moved on by the time his body was found. Without any identification and no one to vouch for him, his fate as a Unknown Soldier should have been sealed.

On October 19, 1863, a description of the photograph (photographs could not be reproduced in newspapers of the time) and the circumstances of the soldier’s death, appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer under the headline Whose Father Was He?

"After the battle of Gettysburg, a Union soldier was found in a secluded spot on the battlefield, where, wounded, he had laid himself down to die. In his hands, tightly clasped, was an ambrotype containing the portraits of three small children ... and as he silently gazed upon them his soul passed away. How touching! How solemn! ... It is earnestly desired that all papers in the country will draw attention to the discovery of this picture and its attendant circumstances, so that, if possible, the family of the dead hero may come into possession of it. Of what inestimable value will it be to these children, proving, as it does, that the last thought of their dying father was for them, and them only." Without a photo, the article had to be as descriptive as possible and included notations on clothes (the eldest boy was wearing a shirt of the same material as the girl’s dress), estimated ages (the 9, 7 and 5 were only a year off) and circumstance (the boy in the center is wearing a dark suit and sitting on a chair). Newspapers across the country picked up the story, and on October 29, 1863, Amos Humiston’s wife, Philinda, read this description in a church magazine called American Presbyterian while at her home in Portville, NY. She suspected the description was of her children Frank, Alice and Freddy, but wrote to Dr. Bourns to be sure. He sent her a copy of the ambrotype. When she opened the envelope, all doubt was removed. The anonymous soldier whose last vision before death were the children he loved, had been her husband, Amos Humiston. Amos is buried in Gettysburg National Cemetery. His headstone bears his name.  Sullivan Ballou Engraved by J.A. O'Neill Library of Congress Sullivan Ballou Engraved by J.A. O'Neill Library of Congress Anyone who has watched the Ken Burns documentary, The Civil War, knows the heartbreaking words written by Rhode Island Major Sullivan Ballou to his wife Sara. The letter, written from his Union Army encampment in Washington D.C. just one week before the first major land battle of the Civil War (Bull Run) is evocative as both a love letter and a statement of purpose. The letter gives us insight into the motives driving the early volunteers called to arms by President Lincoln’s request for 75,000 troops to put down the rebellion in the Cotton 7 states. It also gives us insight into a very human relationship between a man and his wife and children. Headquarters, Camp Clark Washington, D.C., July 14, 1861 My Very Dear Wife: Indications are very strong that we shall move in a few days, perhaps to-morrow. Lest I should not be able to write you again, I feel impelled to write a few lines, that may fall under your eye when I shall be no more. Our movement may be one of a few days duration and full of pleasure and it may be one of severe conflict and death to me. Not my will, but thine, O God be done. If it is necessary that I should fall on the battle-field for any country, I am ready. I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in, the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter. I know how strongly American civilization now leans upon the triumph of government, and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution, and I am willing, perfectly willing to lay down all my joys in this life to help maintain this government, and to pay that debt. But, my dear wife, when I know, that with my own joys, I lay down nearly all of yours, and replace them in this life with care and sorrows, when, after having eaten for long years the bitter fruit of orphanage myself, I must offer it, as their only sustenance, to my dear little children, is it weak or dishonorable, while the banner of my purpose floats calmly and proudly in the breeze, that my unbounded love for you, my darling wife and children, should struggle in fierce, though useless, contest with my love of country. I cannot describe to you my feelings on this calm summer night, when two thousand men are sleeping around me, many of them enjoying the last, perhaps, before that of death, and I, suspicious that Death is creeping behind me with his fatal dart, am communing with God, my country and thee. I have sought most closely and diligently, and often in my breast, for a wrong motive in this hazarding the happiness of those I loved, and I could not find one. A pure love of my country, and of the principles I have often advocated before the people, and "the name of honor, that I love more than I fear death," have called upon me, and I have obeyed. Sarah, my love for you is deathless. It seems to bind me with mighty cables, that nothing but Omnipotence can break; and yet, my love of country comes over me like a strong wind, and bears me irresistibly on with all those chains, to the battlefield. The memories of all the blissful moments I have spent with you come crowding over me, and I feel most deeply grateful to God and you, that I have enjoyed them so long. And how hard it is for me to give them up, and burn to ashes the hopes of future years, when, God willing, we might still have lived and loved together, and seen our boys grow up to honorable manhood around us. I know I have but few claims upon Divine Providence, but something whispers to me, perhaps it is the wafted prayer of my little Edgar, that I shall return to my loved ones unharmed. If I do not, my dear Sarah, never forget how much I love you, nor that, when my last breath escapes me on the battle-field, it will whisper your name. Forgive my many faults, and the many pains I have caused you. How thoughtless, how foolish I have oftentimes been! How gladly would I wash out with my tears, every little spot upon your happiness, and struggle with all the misfortune of this world, to shield you and my children from harm. But I cannot, I must watch you from the spirit land and hover near you, while you buffet the storms with your precious little freight, and wait with sad patience till we meet to part no more. But, O Sarah, if the dead can come back to this earth, and flit unseen around those they loved, I shall always be near you in the garish day, and the darkest night amidst your happiest scenes and gloomiest hours always, always, and, if the soft breeze fans your cheek, it shall be my breath; or the cool air cools your throbbing temples, it shall be my spirit passing by. Sarah, do not mourn me dear; think I am gone, and wait for me, for we shall meet again. As for my little boys, they will grow as I have done, and never know a father's love and care. Little Willie is too young to remember me long, and my blue-eyed Edgar will keep my frolics with him among the dimmest memories of his childhood. Sarah, I have unlimited confidence in your maternal care, and your development of their characters. Tell my two mothers, I call God's blessing upon them. O Sarah, I wait for you there! Come to me, and lead thither my children. - Sullivan Discussion Questions 1. Have you ever received a letter? Why kinds of emotions does it evoke? Do other forms of communication evoke those same emotions or different ones? 2. What does Sullivan say is his motivation for leaving his family and fighting for the Union? 3. Imagine you were living in Rhode Island in 1861 and were undecided about whether to join the fight. If Sara shared her husband’s letter with you, would it convince you to join the army? Would it convince you to stay home? 4. Would this letter be necessarily different if this were written by a volunteer from South Carolina? How would you expect it to differ? How would you expect it would be the same? |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed