An equally important naval technology was developed by private Confederate citizens, leant to the Confederate army and succeed where others before it had failed. And yet, many people have never heard the name of the H.L. Hunley.

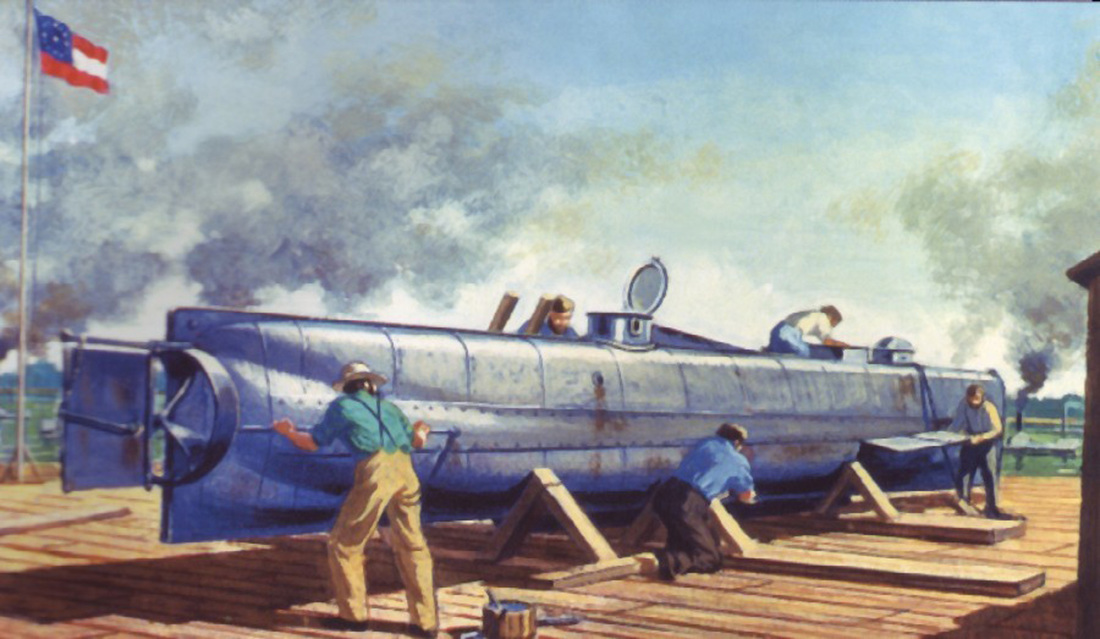

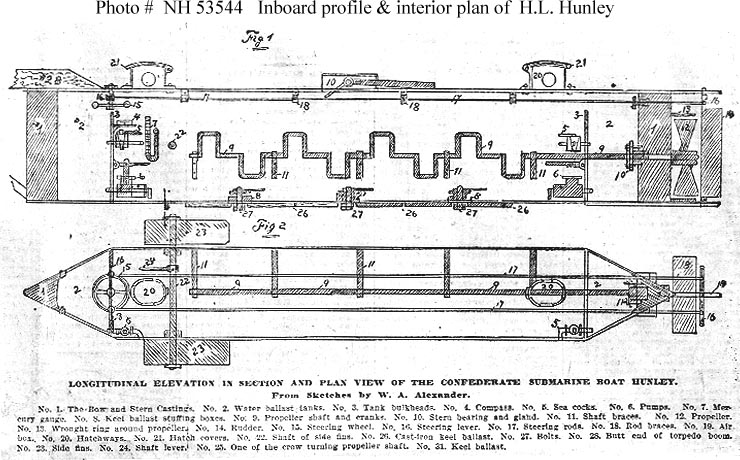

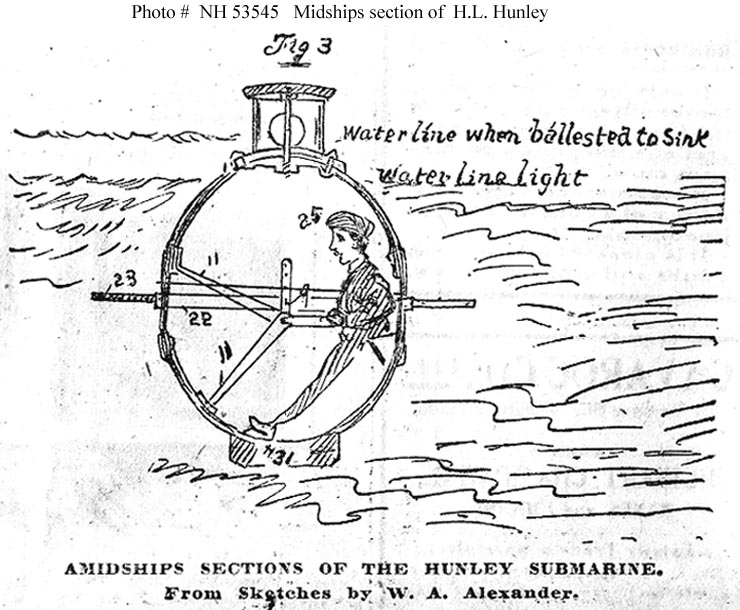

In fact, the Hunley started out its life with the moniker “the fish boat”--an adequate description of what it was: a cigar shaped boat designed to be completely submerged. It was a submarine. The fish boat was 39.5 feet long, 4 feet tall and only 3.83 feet at its widest. The eight crew members entered through one of two oval hatches that were only 14 inches by 16 inches. While they were inside, the captain stood with his head in the front conning tower navigating and working the lever that moved the rudder, and the rest of the crew sat shoulder to shoulder on a narrow wooden bench that extended along the side of the curved wall and bent over a series of connected hand cranks that ran the length of the fish boat. These seven men were the motive power of the boat.

The ship was built in Mobile, Alabama and its original owners Horace Lawson Hunley, James McClintock and Baxter Watson, originally had visions of their fish boat as a privateering ship--a privately owned vessel with authorization from the Confederate government to capture or sink enemy ships for a bounty. They wanted to make money. General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, the Confederate general in charge of the defenses of Charleston, South Carolina, had other ideas. He requested the fish boat’s presence in Charleston. The harbor was being blockaded by the Union fleet. Blockade running ships were fewer and further between and Charleston--the entire Confederacy, in fact--were being choked off from world commerce. Beauregard loved audacious plans. What could be more audacious than using a secret fish boat to blow up Union vessels to destroy the blockade? The boat was transported to Charleston via rail and once it arrived, the crew of eight began sea trials to learn how the boat worked. Only two weeks after the move, the fish boat sank as water entered its open hatches as it was leaving port. Only three of its crew survived. The boat was raised by divers in hard helmets and diving suits, cleaned and returned to service. This time, the handpicked crew would be led by Horace Hunley himself and he officially christened the submarine the H.L. Hunley. He was sure that the first sinking was caused because of the incompetence of the crew and commander who were unfamiliar with the submarine. In October 1863, during a training dive, the Hunley passed beneath the CSS Indian Chief and didn’t come back up. Somehow the crew left open one of the valves that let water into the ballast tank and the boat flooded. All eight men on board died. One of those men was Horace Hunley. The boat was raised again but Beauregard was ready to call it quits. “It is more dangerous to those who use it than the enemy.” Lieutenant George Dixon knew the Hunley. He had been working on it since his regiment, the 21st Alabama, had been reorganized and sent to Mobile for the defense of the city. He had survived a wound to the leg at Shiloh possibly only because the minie ball struck a $20 gold piece that had been in his pocket. He was supposed to have been on the Hunley’s second crew, but had been called back by his unit only days before the fateful training run that ended the lives of all eight crew members. He was lucky. And he knew the Hunley better than anyone else. Dixon convinced Beauregard to let him have one more shot at making the Hunley successful. He was persuasive, and Beauregard got him released from his unit to captain the Hunley. Dixon lead seven other men, all volunteers who knew the boat’s sad history, in training runs based from a dock on Sullivans Island. Finally, the weather cooperated, the crew was ready and Dixon had his target in sight. At about 7:00 pm on February 17, 1864, Dixon and his crew set off toward the large wooden sloop USS Housatonic. His plan was to ram the torpedo which was at the end of a spar that extended from the bow of the ship into the side of the Housatonic, then back away to a safe distance before detonation. They would then show a blue light and the men on shore would answer by lighting a bonfire to guide them back home. At about 8:45 pm, men standing watch on the deck of the Housatonic spotted something that looked like a submerged log moving slowly toward them. They reacted quickly, but the log continued on its approach.

With the sinking of the Housatonic, the Hunley became the first submarine in world history to sink an enemy ship in combat.

But the Hunley never returned. The wreck was found in 1995 and raised in 2000. The remains of all eight crewmen were removed from the wreck and laid to rest in Magnolia Cemetery with the other Hunley crew members who had perished as members of the submarine's first two crews. The submarine is undergoing conservation efforts at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center in North Charleston, South Carolina and the public can see the historic sub on the weekends. Even now, 16 years after the raising of the H.L. Hunley and extensive conservation efforts, it is unclear what happened to the submarine and its third crew. The crew of the Housatonic used small arms to fire on the Hunley as it approached. Did the hail of lead damage the Hunley? Was it damaged by the same torpedo blast that opened the Housatonic’s hull? Did they get turned around and unintentionally head out to the open ocean? Did they simply run out of strength to travel the 5 miles back to their friendly port and drift away exhausted? Or did they simply run out of air? Despite the lingering questions, the H.L. Hunley's place as the first submarine to sink an enemy ship in combat is secure. But one does wonder...can a mission be successful when the crew simply vanishes? Bibliography Raising the Hunley: The Remarkable History and Recovery of the Lost Confederate Submarine by Brian Hicks and Schuyler Kropf The H.L. Hunley: The Secret Hope of the Confederacy by Tom Chaffin Friends of the Hunley Resources

0 Comments

|

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed