During this battle, a cannon ball fired from a Union artillery piece punched through the walls of the Coleman home and wounded Hannah severely. After the ceasefire that announced what would be a lasting peace between the two armies, she was tended to by a Union army doctor at a field hospital set up behind the Coleman home.

Hannah did not survive her wound, which was described by the 8th Maine Volunteer Infantry’s Chaplain, J.E.M. Wright, as “a concave wound…corresponding to the size and shape of the ball.” Hannah was the only civilian casualty of battle and for many years, her story was a tale of a sad irony. The liberating army had arrived, but she had died just hours before the official surrender of the Confederate army made her free. Were that the end of the story, she would probably be confined to a footnote of history. However, in preparation for the April 2015 sesquicentennial of the battle and subsequent surrender, the National Park Service tasked local Appomattox Pastor Alfred L. Jones III with writing and delivering a eulogy for Hannah as part of its commemoration. The program, Footsteps to Freedom, celebrated the life of Hannah and the freedom granted by the Confederate army's surrender to the 4,600 Appomattox County slaves. In his research about Hannah, Jones came across a document that redefined Hannah’s life: a death registry. In it, Hannah Reynold’s death date is listed as April 12, 1865, not April 9 as was always assumed. The difference in those three days meant the difference between dying a slave hours short of liberation and dying a free woman. The importance did not appear to be lost on Dr. Coleman, who was listed in the register as the person who reported Hannah’s death. He listed himself as Hannah’s “former owner”. Hannah’s funeral, held April 11, 2015, featured Pastor Jones’ eulogy, a 100 member gospel choir and 4,600 luminaries—one for each slave in Appomattox County liberated by the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia. Discussion Questions 1. What reasons could Hannah and Abram have had for staying in the Coleman home after their master left? Why do you think they didn’t take the opportunity to escape to the Union army lines? 2. What defines home to you? Would you risk your life to protect it? 3. If Hannah had been conscious, how do you think she may have responded to the idea of dying a free woman? 4. Is there an intrinsic value to freedom that transcends a person’s ability to take advantage of it? References and Further Reading Discovery Gives New Ending to a Death the Civil War's Close Funeral for a Former Slave Takes Center Stage at Appomattox 'Wounded as a Slave; Died as a Free Woman': Appomattox Anniversary Program to Honor Hannah Reynolds

0 Comments

As a historian and a bibliophile, I have a soft spot in my heart for children’s books that stress famous historic figures’ interest in, and love of, reading. In Words Set Me Free, Lisa Cline-Ransome uses the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave to set the stage for one of Frederick Douglass’s main thematic threads in his autobiography: education was the key to true freedom.

Cline-Ransome begins with the story of Douglass’s early life and chooses some of the most dramatic images from the Narrative to include:

She also uses a portion of Hugh Auld’s declaration to his wife to show the reason that education, in this case the ability to read, would become so important to Douglass: “He should know nothing but to obey his master--to do as he is told to do. If you teach him how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave.” From that moment on, Douglass determines if reading will unfit him to be a slave, then he must learn to read. Cline-Ransome takes us through Douglass’s learning process and how he bartered with and tricked the local boys into teaching him his letters. Even the iconic moment from the Narrative, Douglass’s lamenting over the fact that the ships he watched sail out to see had more freedom than he himself had, makes an appearance in this book. There are a few drawbacks. The language used is easy for adults, but the sentence structure and language may be too complex for younger children. The very first page of the book has two examples: “After I was born, they sent me to my Grandmamma and my Mama to another plantation," and “Cook told me my mother took sick. I never saw her again.” This is not necessarily a bad thing, but be prepared for questions from younger readers. I also dislike the ending of the book. The Epilogue describes Douglass’s first escape attempt in 1835, in which he and several slaves from the plantation tried to escape with forged passes. If you stop reading here--as many would after an Epilogue--and have no more knowledge of Douglass’s story than what is in this book, you would be left with the impression that this escape attempt was successful. It was not. The rest of the story is buried in an Author’s Note on the bibliographical page in the very end of the book. All in all, this is a good introduction to the life of Frederick Douglass for young elementary students, and also provides a historical reference to encourage an interest in, and love of, reading.

If you proclaim an interest in the Civil War, there are a few books that it is assumed you have read. At the top of that list is Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave. One of the best known slave narratives, this autobiographical book packs a big punch in fewer than 100 pages.

At its most basic level, it tells the story of Frederick Douglass’s life in slavery and his escape from it. He details brutality at the hands of some masters and consideration at the hands of others. He tells about times of abundance and times of scarcity. He tells of the tasks he was set to do and those which he chose for himself, often, like his Sabbath School classes, in secret. If this was all that was in this book, it would be enough. But the book also contains a significant amount of subtext that challenges the status quo of Antebellum America. Douglass is a master story teller using classic literature and the Bible to deliver an abolitionist sermon, especially aimed at northern Christians who were turning a blind eye to slavery. In fact, one of the overriding themes of this work is that Christianity is an aggravating factor in slavery, not a mitigating one. The masters who most conspicuously proclaimed themselves Christians were the worst masters. Further, Douglass's subtitle to this work--An American Slave--was, I believe, an intentional choice meant to claim the sin of slavery for the entire nation. Everyone--northerners and southerners, slave holders and free-labor proponents, Christians and non-Christians alike--were complicit in slavery. No one's hands were clean. The impact slavery has on the enslaved is the central theme to many studies of the time, but in the person of Sophia Auld, Douglass illustrates the impact slavery has on the enslavers. When he first meets her, Douglass describes Sophia as “a woman of the kindest heart and finest feelings. She had never had a slave under her control previously to myself, and prior to her marriage she had been dependent upon her own industry for a living.” He claimed to be “astonished by her goodness.” Sophia taught Douglass the alphabet and the rudiments of reading. When her husband, Douglass’s master Hugh Auld, discovered this, he put an immediate stop to it. “If you give a n-- an inch, he will take an ell. A n-- should know nothing but to obey his master--to do as he is told to do. Learning would spoil the best n-- in the world. Now, if you teach that n-- how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanagable and of no value to his master. As to himself, it could do him no good, but a great deal of harm. It would make him discontented and unhappy.” Douglass notes that from that moment on, Sophia Auld began to lose those qualities--piety, warmth, charity and tenderness--that had so thrilled Douglass upon his first meeting her. Her heart grew hard. Douglass even acknowledges, “Slavery proved as injurious to her as it did to me.” Hugh Auld’s lecture to his wife also introduces another central theme: slavery was more than simply bondage of the body. It was bondage of the mind. Douglass understood from that moment on that education was the key to true freedom. Hugh Auld was right. Education would make him discontent and unhappy. Douglass would spend the rest of his childhood as a slave bartering what he could with local boys to get them to teach him to read. When he had nothing to barter, he would dupe those same boys into teaching him by issuing challenges he knew the boys couldn’t ignore. Once he knew how to read, he organized secret Sabbath Schools to help other slaves gain the education that had so discontented Douglass. The original Preface, written by William Lloyd Garrison, can be a barrier. Garrison wrote like someone who liked to hear himself talk. His writing is bombastic in the formal and rather overblown language of orators of the time, and Douglass’s clear and concise writing is a welcome read after the multipage Preface. There are many editions of this book. While the main body’s text will remain the same, some editions provide additional information that will help provide context and further understanding of this deceptively complex work. I read a 1993 edition edited by David Blight. Blight’s footnotes and the supplemental materials highlight the rich literature Douglass drew upon to write his autobiography, and give a glimpse into his subsequent public work. While this particular text is out of print, it can be found used on Amazon and abebooks.com.

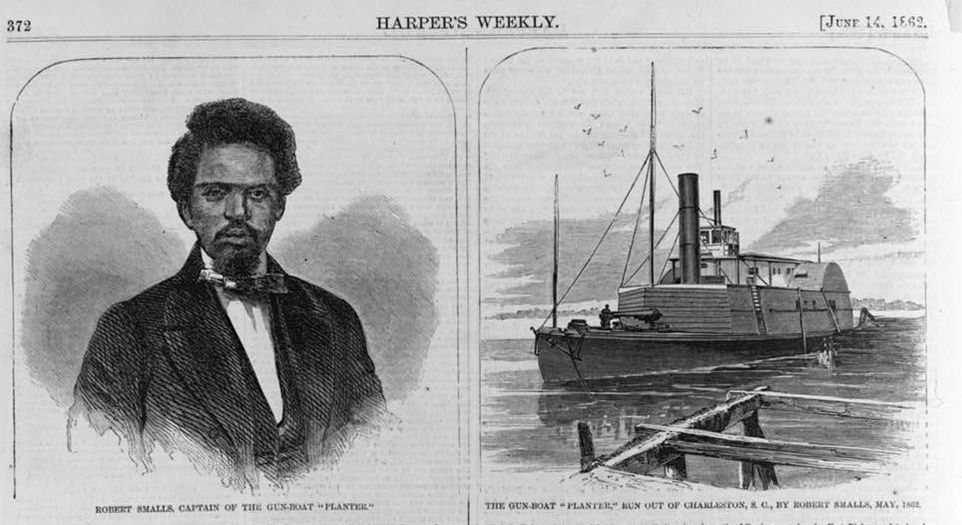

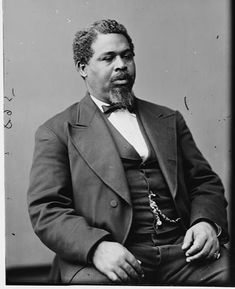

Last week, I shared with you the story of Robert Smalls, who made a daring escape from freedom by stealing a boat in Charleston Harbor. The story is exciting and highlights the lengths to which some slaves would go to secure their freedom.

Seven Miles to Freedom tells the story of Robert Smalls from his birth though the successful escape in a format illustrated with beautiful impressionistic paintings. The story starts off with the author drawing the biographical background of Robert’s life on the McKee plantation in Beaufort, South Carolina. Robert tells of the horrors of slavery that he sees on other plantations, but proclaims his master to be good and fair and himself to be treated well. But his personal experience doesn’t temper his hated of slavery. Halfmann introduces us to Hannah, whom Robert falls in love with and marries. The two are lucky in that their masters allow them to live together. When Robert and Hannah’s daughter is born, the two are able to negotiate with Mr. Kingman, Hannah’s owner, for the eventual purchase price of Hannah and their daughter for a sum of $800. To help the couple earn the money, both Mr. Kingman and Robert’s owner, Mr. McKee, allowed them to hire themselves out, and keep all of their earnings but $15 a week paid to Mr. McKee and $7 a week paid to Mr. Kingman. On the verge of having enough to earn his wife’s and daughter’s freedom, the Civil War erupts in nearby Charleston Harbor. Robert reluctantly becomes part of the Confederate war effort as the ship he is the wheelman on, the Planter, is enlisted by the Confederate government to strengthen the harbor defenses by laying mines and destroying lighthouses. One evening, the white crew prepared to leave the boat. Before they left, they jokingly place the captain’s distinctive straw hat on Robert’s head. The simple act is the inspiration for Robert’s daring escape attempt. Halfmann describes the plan. On the next night that the white crew leaves, they will take the boat, pick up their loved ones, and sail out to the Union blockade, with Robert posing as the ship’s captain, straw hat and all. If they are caught, everyone agrees they will sink the boat and if the process takes too long, they will hold hands and jump overboard to drown themselves. They refuse to go back to a life of bondage. Halfmann’s strength is in the narration of the escape attempt. The rather slow and ordinary beginning of the book hits its stride when Robert’s plan is executed. I am always impressed by authors who are able to achieve suspense when its readers know (or can easily find out ) how the story actually ends. Halfmann succeeds here, creating a “hold your breath” moment as Robert slides the ship past Fort Sumter as the sun rises and his cover could be blown. This book works on several levels. First, it is an engaging story on the surface. Who doesn’t love a good, suspenseful escape from bondage story that allows you to cheer at the end? Second, for older children, the way Halfmann writes provides great opportunities to discuss the meaning of freedom:

There is some rather archaic language, as the author chooses to use the word “colored” on several occasions. This can be a bit of a shock for a book published in 2008. And I take a bit of exception to the idea that Robert knew, in 1861 , that a Union victory in the Civil War meant the abolition of slavery. At that time in the war, that conclusion could not be drawn, as the federal government was fighting for Union. Lincoln, after issuing the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September of 1862, used the carrot of retained slavery to entice the recalcitrant Confederate states back into the Union before the Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863. Had any slave state chosen to return to the Union prior to that date, slavery would have been protected as it continued to be in the Union-loyal slave holding border states. Robert Smalls was not a steamship pilot for the Confederacy. He was responsible for maneuvering the side wheel steamer, Planter, through the dangers of Charleston harbor to the relative safety of open water. Though those happened to be the same duties as a boat’s pilot, he was instead given the title of wheel man. Only white men could be pilots. The wages he earned were the property of the master who had hired him out. He was aiding the Confederate war effort by strengthening the defenses of Charleston Harbor. He helped lay torpedoes (mines) in the channels, destroyed a lighthouse, and brought supplies to the Charleston area forts. And he wanted the Union to win the war. When the sun fell on the evening of May 12, 1862, the three white crewmembers from the Planter defied Confederate regulations by leaving the boat for the evening. They trusted Smalls and the other slaves who remained on board. When it became evident that the Confederate sailors were not coming back that evening, Smalls shared with his fellow slaves a daring plan. Just before dawn, Smalls and a crew of eight, along with five women and three children-including Smalls' wife and children, eased the Planter from the dock. They knew their plan was daring and dangerous. If, at any point in the next few hours their plan failed, everyone agreed that they would blow up the boat. For them, it was freedom or death. Smalls wore the straw hat that the boat’s captain usually donned on his rounds, and convincingly mimicked the captain’s posture so well that in the uncertain pre-dawn light, no one from the forts questioned the boat or crew as they moved through the harbor, flashing all the correct secret signals so as not to attract attention. Once they were out of range of the forts' cannons, the South Carolina and Confederate flags were struck, and they ran up a white bed sheet that had been brought onboard by Smalls' wife. The Planter and its crew set their sights on the ships of the Union blockade. An eyewitness aboard the USS Onward, the nearest ship, described what happened next, ““Just as No. 3 port gun was being elevated, someone cried out, ‘I see something that looks like a white flag’; and true enough there was something flying on the steamer that would have been white by application of soap and water. As she neared us, we looked in vain for the face of a white man. When they discovered that we would not fire on them, there was a rush of contrabands out on her deck, some dancing, some singing, whistling, jumping; and others stood looking towards Fort Sumter, and muttering all sorts of maledictions against it, and ‘de heart of de Souf,’ generally. As the steamer came near, and under the stern of the Onward, one of the Colored men stepped forward, and taking off his hat, shouted, ‘Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!’ ”(James McPherson, The Negro's Civil War) Robert Smalls and his small band on the planter were slaves no longer. Though the Emancipation Proclamation had not been issued yet, Congress had already passed the First Confiscation Act permitting the confiscation of any property, including slaves, being used to support the Confederate war effort. They were free.

Nearly 179,000 former slaves and freedmen fought in the Union Army, making up almost 10% of the United States’ total fighting force. Another 17,000 served with the Union Navy. We will take a look at how regiments of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) played an important role in the battles that raged across the country.

We will look at civilians, too. There were those who made dramatic escapes and set about taking an active role in improving the lives of others. There were those who remained in bondage until the very end and whose stories are still being written. There were those who liberated themselves by escaping to the Union Army and taking the first step to creating a free society for African Americans. Join us this month for stories of the African-American history-makers of the Civil War. |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed