|

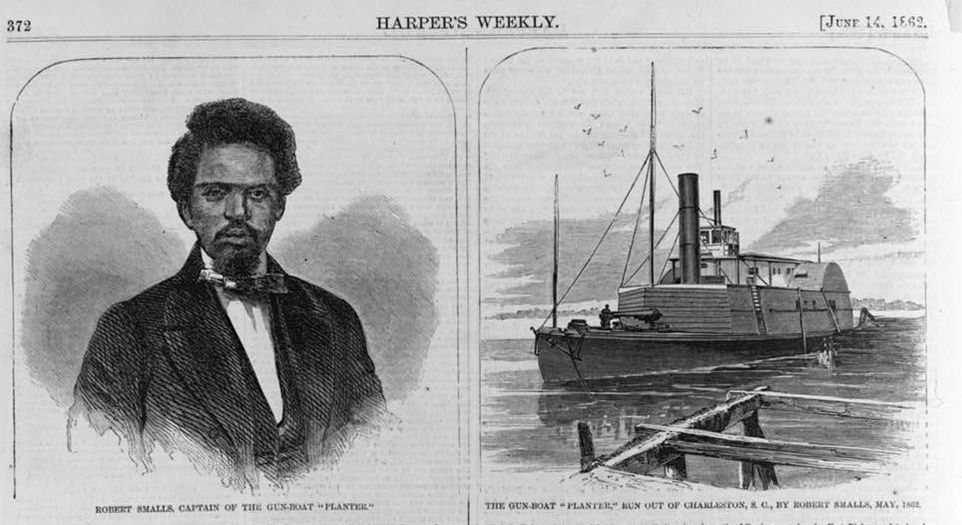

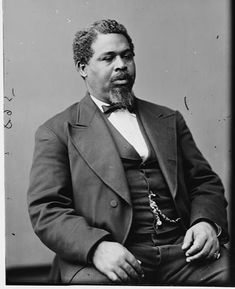

Robert Smalls was not a steamship pilot for the Confederacy. He was responsible for maneuvering the side wheel steamer, Planter, through the dangers of Charleston harbor to the relative safety of open water. Though those happened to be the same duties as a boat’s pilot, he was instead given the title of wheel man. Only white men could be pilots. The wages he earned were the property of the master who had hired him out. He was aiding the Confederate war effort by strengthening the defenses of Charleston Harbor. He helped lay torpedoes (mines) in the channels, destroyed a lighthouse, and brought supplies to the Charleston area forts. And he wanted the Union to win the war. When the sun fell on the evening of May 12, 1862, the three white crewmembers from the Planter defied Confederate regulations by leaving the boat for the evening. They trusted Smalls and the other slaves who remained on board. When it became evident that the Confederate sailors were not coming back that evening, Smalls shared with his fellow slaves a daring plan. Just before dawn, Smalls and a crew of eight, along with five women and three children-including Smalls' wife and children, eased the Planter from the dock. They knew their plan was daring and dangerous. If, at any point in the next few hours their plan failed, everyone agreed that they would blow up the boat. For them, it was freedom or death. Smalls wore the straw hat that the boat’s captain usually donned on his rounds, and convincingly mimicked the captain’s posture so well that in the uncertain pre-dawn light, no one from the forts questioned the boat or crew as they moved through the harbor, flashing all the correct secret signals so as not to attract attention. Once they were out of range of the forts' cannons, the South Carolina and Confederate flags were struck, and they ran up a white bed sheet that had been brought onboard by Smalls' wife. The Planter and its crew set their sights on the ships of the Union blockade. An eyewitness aboard the USS Onward, the nearest ship, described what happened next, ““Just as No. 3 port gun was being elevated, someone cried out, ‘I see something that looks like a white flag’; and true enough there was something flying on the steamer that would have been white by application of soap and water. As she neared us, we looked in vain for the face of a white man. When they discovered that we would not fire on them, there was a rush of contrabands out on her deck, some dancing, some singing, whistling, jumping; and others stood looking towards Fort Sumter, and muttering all sorts of maledictions against it, and ‘de heart of de Souf,’ generally. As the steamer came near, and under the stern of the Onward, one of the Colored men stepped forward, and taking off his hat, shouted, ‘Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!’ ”(James McPherson, The Negro's Civil War) Robert Smalls and his small band on the planter were slaves no longer. Though the Emancipation Proclamation had not been issued yet, Congress had already passed the First Confiscation Act permitting the confiscation of any property, including slaves, being used to support the Confederate war effort. They were free.

0 Comments

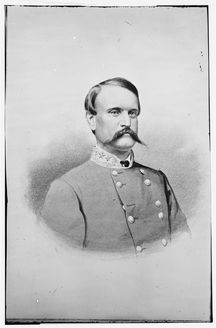

All they wanted was to be given the chance to show that the years they had spent training to be the next generation of Virginia’s military and political leaders hadn’t been wasted. What better way to prove their military training than during a real life, honest to goodness war? The cadets of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) believed their opportunity had finally presented itself. But over three years after the first shots of the Civil War, the 260 or so cadets of VMI—most aged 15 to 18 years old--had still not been called to fight for their cause. Certainly, the leaders in Richmond wanted to preserve the next generation of leaders from the dangers of combat; but they also needed their particular expertise in military discipline and drill. So the cadets had been called upon to train Virginia militia units before those units would take off to the front lines, leaving the boys behind. VMI, in the picturesque town of Lexington, was located along one of the most well-traveled and important valleys in all the Confederacy. The Shenandoah Valley runs along the Blue Ridge Mountains from southwest to northeast. The valley opens up near Harpers Ferry in what is now West Virginia, a mere 60 miles—or three days hard march—from Washington, DC and Baltimore. It was fertile farm land, had a good road running its length, and was a loaded gun pointed at important Northern cities. There had been extensive fighting throughout the Valley in 1862, when Union General Nathaniel Banks lost—as in couldn’t find—Stonewall Jackson and his army before Banks decided that the Confederate army outnumbered him (it did not) and that he was a sitting duck for destruction (only in his own mind) and abandoned the Valley. Given the importance of the Valley, it is remarkable that by 1864, the cadets of VMI were still looking for their first chance to “see the elephant.” In May of 1864, the new General in Chief of the Federal forces, US Grant, was ready to execute a grand strategic plan for every Union army fighting in the war. His plan for the spring campaign was a series of coordinated attacks on several of the Confederacy’s fronts, including the Shenandoah Valley.

On May 11, 1864, the Cadets received the news they had been waiting for: Headquarters Va. Mil. Institute May 11, 1864 General Orders No. 18 I.Under the orders of Maj. Gen'l John C. Breckinridge, Commd'g Dept of Western Virginia, the Corps of Cadets and a Section of Artillery will forthwith take up the line of march for Staunton, Va., under the command of Lieut. Col. Scott Shipp. The Cadets will carry with them two days rations. II.Captain J. C. Whitwell will accompany the expedition as Asst. Qr. Master and Commissary and will see that the proper transportation &c is supplied. III.Surgeon R. L. Madison and Asst. Surgeon Geo. Ross will accompany the expedition and attend to the care of the sick and wounded. IV.Col. Shipp on arriving at Staunton will report in person to Maj. Gen'l Breckinridge and await his further instructions. V.Captain T. M. Semmes is assigned to temporary duty on the Staff of the Commd'g Officer. By Command Maj. Gen'l F. H. Smith {Signed} J. H. Morrison, A. A. V. M. Inst. The boys were on their way to war. General Breckinridge only called forth the Cadets out of desperate necessity. He was uneasy about the prospect of actually allowing the Cadets to engage the enemy. “They are only children," he told an aide, "and I cannot expose them to such fire." It was his intention to keep the boys in reserve, hopefully protecting them from battle. But as the battle opened north of New Market, Virginia, on May 15, 1864, the Confederates were still significantly outnumbered. The 257 Cadets, while held behind the main line, were to play a pivotal role in the fighting around the Bushong family’s farm. The Union troops had taken position on a hill north of the Bushong farm house. The infantry was supported by artillery. It was a strong position, and the Cadets were marching toward it. As they marched up and over Shirley Hill, the Cadets came into artillery range. They were ordered to stop and discard their blankets and packs. Then they formed up in the third echelon, supporting veteran troops as they moved forward to attack. As the 51st Virginia Infantry and the 30th Virginia Infantry Batallion neared the area of the Bushong farm house, it came under withering fire and was cut to pieces, causing soldiers in the units to retreat in disorder and stalling the Confederate advance. There was now a dangerous gap in the grey line. Breckinridge gave the order. “Put the boys in…and may God forgive me for the order.” The Cadets moved into the Bushong orchard under heavy fire. Still, they advanced. They charged forward to the remains of a wooden fence and, laying down, opened fire for the first time. They were in this position only about 20 minutes when Confederate forces tuned the Union right flank on top of the hill and the artillery and infantry fire facing the Cadets slowed considerably. It was then the Cadets were ordered to charge. They rallied around their colors and rushed through a wheat field, and then through a recently plowed farm field that had been turned to mud by the previous days' rains. The mud was so thick it sucked the shoes from the boys’ feet. Even so, the Cadets were able to capture two Union artillery pieces and between 60-100 troops before the Federal forces retreated from the field. It may have been a time for gleeful celebration, but the Cadets had come on to the field 257 strong. During the battle five Cadets had been killed in action, and another five would die from wounds they sustained during the fight. 45 other Cadets were wounded, though not mortally. The battle was a Confederate victory that tuned back the Union advance. General Sigel was soon replaced by David Hunter who would advance back up the Valley and in June, burn down the campus of VMI. The Field of Lost Shoes holds a special place in VMI history. Every year, first year Cadets, known as Rats, visit the New Market battlefield and charge across the Field of Lost Shoes before they officially take their oath of Cadetship. The Field also evokes a powerful image of lost youth. Much like the empty boots in the stirrups of a riderless horse, the idea of empty shoes being pulled out of a muddy morass conjures images of boys charging forward into battle, lost forever to the innocence of childhood--or lost even to life itself. Cadets Killed at the Battle of New Market

Johnny was with the regiment when it engaged the Confederate army on the afternoon of September 20, 1863 along a creek in north Georgia called Chickamauga. On that day, Johnny shed his drum and instead carried a rifle musket, trimmed down from regulation length to fit his short stature. The battle was chaotic and the 22nd Michigan was being surrounded when a Confederate Colonel noticed the child soldier with his shortened weapon. The Colonel demanded that Johnny surrender by saying “I think the best thing a mite of a chap like you can do is drop that gun”. Johnny disagreed. In his opinion, the best thing he could do was to use it. He refused to surrender and instead shot the Colonel and headed back to his unit. Johnny, who at some point during the war officially changed his name to John Lincoln Clem to honor the President, was rewarded for his bravery under fire with a promotion to sergeant, becoming the youngest non-commissioned officer in the history of the United States Army. And the American public granted him another laurel wreath, deeming him “The Drummer Boy of Chickamauga.” The harrowing times were not over for Johnny. In October of 1863, he was detailed as a train guard when Confederate cavalry captured him. He was take prisoner and had taken from him his Union uniform, including his prized hat which sported three bullet holes it had received at Chickamauga. He was released in a prisoner exchange not long after, and would go on to fight in other battles as the armies marched toward Atlanta. John Clem was officially discharged a year after his harrowing experience at Chickamauga in September 1864. But John Lincoln Clem was not done with the army. After graduating high school in 1870, he tried--and failed--to pass the entrance exam for the West Point Military Academy. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him second lieutenant in the 24th US Infantry and over the years, he steadily moved up the ranks and upon retirement was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General. In honor of his service, upon his death in 1937, he was buried in Arlington Cemetery,

Even without the feats ascribed to "Johnny Shiloh", the events that young Johnny Clem experienced before he turned 14 make his life a fascinating story that shows that often, children are capable of more than we could ever give them credit for.

References and Further Reading John Clem, Drummer Boy of Chickamauga The Boys of War The Drummer Boy of Shiloh by WS Hays Imagine you are 19 (again?). What is your plan for your life? Was your answer earning a statue and eternal fame?

Well, to be honest, if he was asked that same question on the morning of December 13, 1862, it is likely Sergeant Richard Rowland Kirkland wouldn’t have answered that way either. The 19 year old was in the 2nd South Carolina Infantry and positioned behind a stone wall that fronted a sunken road called the Telegraph Road near the top of Marye’s Heights. Below him, he would have seen an empty field gradually sloping from his position to the edge of the town of Fredericksburg, Virginia, and beyond it, the Rappahannock River. From across the river, lines of blue-clad troops tromped across pontoon bridges and up through the streets of the town. As they reached the edge of the empty field, Union soldiers moved into line of battle and began their march toward the strong defenses anchored by the four foot stone wall in front of 9,000 Confederate troops, the 2nd South Carolina and Richard Kirkland among them. Kirkland would have seen 14 separate attacks come up the plain and falter hundreds of feet from their goal of the stone wall, the Union troops cut down in rows by the withering infantry and artillery fire. It turned out that Confederate artillerist E. Porter Alexander’s prediction had been true. “A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it.” Not a chicken, or very many men. The most successful of the repeated charges only came within 40 yards of the stone wall before breaking. That night, thousands of Union soldiers lay on the slope, some dead, some dying, and many wounded. Those who were still alive were cold. Those who could still grip their weapons were taking shots at the Confederates who remained behind the wall and who were returning their fire in measure. There was moaning, crying and prayers going up from the men on the field. Men begged for water, and peace. The cries were not easy to ignore for young Sergeant Kirkland. They continued all night and into the next day. By the afternoon of December 14, Sergeant Kirkland had had enough. He approached his brigade commander, General Joseph B Kershaw to ask permission to give the suffering Union wounded water. Kershaw attempted to dissuade him by pointing out the possibility—rather, the likelihood—of getting shot for his efforts, but Kirkland persisted. He asked if he could take a white handkerchief with him on his errand but was denied. He chose to go anyway. Kirkland stepped over the wall, and reached the nearest wounded soldier. “He knelt beside him, tenderly raised the drooping head, rested it gently upon his own noble breast, and poured the precious life-giving fluid down the fever scorched throat. This done, he laid him tenderly down, placed his knapsack under his head, straightened out his broken limb, spread his overcoat over him, replaced his empty canteen with a full one, and turned to another sufferer.” (Kershaw, Humane Hero of Fredericksburg, Letter to Charleston News and Courier, January 2, 1880). Once soldiers understood his purpose, they ceased their fire. For an hour and a half, Kirkland ministered in this way to the fallen enemy before returning to his lines. Kirkland survived the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg before being sent to north Georgia with the rest of Longstreet’s Corps in September 1863. He arrived on the battlefield at Chickamauga too late to participate in the first day’s action, but was heavily involved in the second day’s route of the Federal army from the field. He was shot on Snodgrass Hill and killed. In 1965, the National Park Service installed a statue to Richard Kirkland along the stone wall and sunken road at the Fredericksburg battlefield near the site where he gave so much comfort to the wounded enemy. It is called The Angel of Marye’s Heights. There has been recent scholarship that calls into question the accuracy of this story. Did it happen the way General Kershaw told it? Did it happen at all? There is no mention of the act in the after action reports. None of his fellow soldiers mention seeing it. There does not appear to have been the hour and a half cease fire during which Kirkland carried out his mission. Does this mean it didn’t happen? The story came to the attention of the general public when, in 1880, General Kershaw, Kirkland’s brigade commander, recorded Kirkland’s daring acts in a letter written to, and published in, the Charleston News and Courier. Kershaw’s letter was written during Reconstruction, a time when the country was being put back together piece by piece. It is possible that his intention in writing his letter was to demonstrate a friendship and mercy between the two sides that illustrated the hope of the mending country. The erection of the statue by the National Park Service in 1965 may also be symbolic of a desired peace between enemy combatants that was missing during the height of the cold war. Discussion Questions Read Richard Kirkland, The Humane Hero of Fredericksburg and Is the Richard Kirkland Story True? 1. Do you think the story of Richard Kirkland is true as Kershaw presents it? Is Kershaw’s tale an embellishment? A fabrication? Why? 2. What lesson can be learned from the story of Richard Kirkland? Does that lesson change if the story is exaggerated or fabricated? 3. Have you ever been in a situation, or known of someone in a situation, where they risked personal safety to provide comfort to someone? Under what circumstances, if any, could you imagine yourself doing so? |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed