Intelligence Report--Cadets At War: The True Story of Teenage Heroism at the Battle of New Market1/25/2017

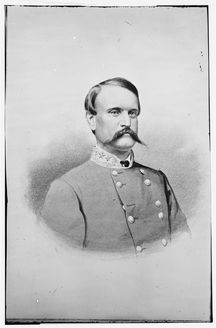

Earlier this week, I shared the story of the VMI Cadets' coming of age. On May 15, 1864, 257 cadets from the Virginia Military Institute ranging in age from 15 to 19 years old put their military training to the test. For many of these cadets, this was the first time in a live combat situation. They were supposed to be the reserve of the Confederate Army operating under General Breckinridge. After a Confederate regiment from Missouri was cut to pieces, General Breckinridge gave the order he dreaded: “Put the boys in, and may God forgive me for the order.”

This book from Susan Provost Beller looks at personal letters and cadet files in the VMI archives to give a voice to that small number of cadets who helped the Confederates turn the tide of the battle. Beller begins with providing a bit of background, takes us with the cadets as they march north (“down the valley”) toward New Market, advance around the Bushong Farm House and through a muddy field (the Field of Lost Shoes) and finally as they defend their honor in the press and public perception years after the guns have gone silent. The book is less than 100 pages long, so the background on the cadets and the battle is necessarily brief. The battle scenes have urgency and don’t get bogged down in lots of minutia. Beller’s use of the words and stories of only a few of the cadets gives the book focus. However, the maps are hand drawn and difficult to read. The illustrations, with the exception of the cadet photos, did not reproduce well. Both maps and illustrations fail to adequately support the text. The writing style is very casual; the author writes how I imagine she speaks. She mentioned in the introduction she has shared this story with school groups many times, and it sounds as if she simply provided a transcription of one of those presentations. It is probably beneficial for young readers, but for me, it lacked authority. One final thing that that is only incidental to the story but that bothers me enough to correct--or perhaps better explain--why going north through the Shenandoah Valley is actually “down the valley” while going south is “up the valley.” She gives a vague reason tied to Pennsylvania settlers moving south away from civilization and into the unknown, so they called it going “up the valley.” The real answer is much more concrete and even simpler: the Shenandoah River flows from south to north toward its confluence with the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry, WV. Therefore going south is going upriver—up the valley—and going north is going downriver—down the valley. It almost makes me call into question all of the research she did for this book. Thankfully, she quoted letters and official records enough that the voices of the cadets are authentic.

1 Comment

All they wanted was to be given the chance to show that the years they had spent training to be the next generation of Virginia’s military and political leaders hadn’t been wasted. What better way to prove their military training than during a real life, honest to goodness war? The cadets of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) believed their opportunity had finally presented itself. But over three years after the first shots of the Civil War, the 260 or so cadets of VMI—most aged 15 to 18 years old--had still not been called to fight for their cause. Certainly, the leaders in Richmond wanted to preserve the next generation of leaders from the dangers of combat; but they also needed their particular expertise in military discipline and drill. So the cadets had been called upon to train Virginia militia units before those units would take off to the front lines, leaving the boys behind. VMI, in the picturesque town of Lexington, was located along one of the most well-traveled and important valleys in all the Confederacy. The Shenandoah Valley runs along the Blue Ridge Mountains from southwest to northeast. The valley opens up near Harpers Ferry in what is now West Virginia, a mere 60 miles—or three days hard march—from Washington, DC and Baltimore. It was fertile farm land, had a good road running its length, and was a loaded gun pointed at important Northern cities. There had been extensive fighting throughout the Valley in 1862, when Union General Nathaniel Banks lost—as in couldn’t find—Stonewall Jackson and his army before Banks decided that the Confederate army outnumbered him (it did not) and that he was a sitting duck for destruction (only in his own mind) and abandoned the Valley. Given the importance of the Valley, it is remarkable that by 1864, the cadets of VMI were still looking for their first chance to “see the elephant.” In May of 1864, the new General in Chief of the Federal forces, US Grant, was ready to execute a grand strategic plan for every Union army fighting in the war. His plan for the spring campaign was a series of coordinated attacks on several of the Confederacy’s fronts, including the Shenandoah Valley.

On May 11, 1864, the Cadets received the news they had been waiting for: Headquarters Va. Mil. Institute May 11, 1864 General Orders No. 18 I.Under the orders of Maj. Gen'l John C. Breckinridge, Commd'g Dept of Western Virginia, the Corps of Cadets and a Section of Artillery will forthwith take up the line of march for Staunton, Va., under the command of Lieut. Col. Scott Shipp. The Cadets will carry with them two days rations. II.Captain J. C. Whitwell will accompany the expedition as Asst. Qr. Master and Commissary and will see that the proper transportation &c is supplied. III.Surgeon R. L. Madison and Asst. Surgeon Geo. Ross will accompany the expedition and attend to the care of the sick and wounded. IV.Col. Shipp on arriving at Staunton will report in person to Maj. Gen'l Breckinridge and await his further instructions. V.Captain T. M. Semmes is assigned to temporary duty on the Staff of the Commd'g Officer. By Command Maj. Gen'l F. H. Smith {Signed} J. H. Morrison, A. A. V. M. Inst. The boys were on their way to war. General Breckinridge only called forth the Cadets out of desperate necessity. He was uneasy about the prospect of actually allowing the Cadets to engage the enemy. “They are only children," he told an aide, "and I cannot expose them to such fire." It was his intention to keep the boys in reserve, hopefully protecting them from battle. But as the battle opened north of New Market, Virginia, on May 15, 1864, the Confederates were still significantly outnumbered. The 257 Cadets, while held behind the main line, were to play a pivotal role in the fighting around the Bushong family’s farm. The Union troops had taken position on a hill north of the Bushong farm house. The infantry was supported by artillery. It was a strong position, and the Cadets were marching toward it. As they marched up and over Shirley Hill, the Cadets came into artillery range. They were ordered to stop and discard their blankets and packs. Then they formed up in the third echelon, supporting veteran troops as they moved forward to attack. As the 51st Virginia Infantry and the 30th Virginia Infantry Batallion neared the area of the Bushong farm house, it came under withering fire and was cut to pieces, causing soldiers in the units to retreat in disorder and stalling the Confederate advance. There was now a dangerous gap in the grey line. Breckinridge gave the order. “Put the boys in…and may God forgive me for the order.” The Cadets moved into the Bushong orchard under heavy fire. Still, they advanced. They charged forward to the remains of a wooden fence and, laying down, opened fire for the first time. They were in this position only about 20 minutes when Confederate forces tuned the Union right flank on top of the hill and the artillery and infantry fire facing the Cadets slowed considerably. It was then the Cadets were ordered to charge. They rallied around their colors and rushed through a wheat field, and then through a recently plowed farm field that had been turned to mud by the previous days' rains. The mud was so thick it sucked the shoes from the boys’ feet. Even so, the Cadets were able to capture two Union artillery pieces and between 60-100 troops before the Federal forces retreated from the field. It may have been a time for gleeful celebration, but the Cadets had come on to the field 257 strong. During the battle five Cadets had been killed in action, and another five would die from wounds they sustained during the fight. 45 other Cadets were wounded, though not mortally. The battle was a Confederate victory that tuned back the Union advance. General Sigel was soon replaced by David Hunter who would advance back up the Valley and in June, burn down the campus of VMI. The Field of Lost Shoes holds a special place in VMI history. Every year, first year Cadets, known as Rats, visit the New Market battlefield and charge across the Field of Lost Shoes before they officially take their oath of Cadetship. The Field also evokes a powerful image of lost youth. Much like the empty boots in the stirrups of a riderless horse, the idea of empty shoes being pulled out of a muddy morass conjures images of boys charging forward into battle, lost forever to the innocence of childhood--or lost even to life itself. Cadets Killed at the Battle of New Market

|

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed