|

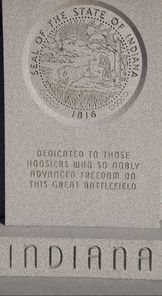

With all of the attention on Confederate monuments recently, I am happy that at least some of the discussion is around the idea that monuments are frequently inaccurate representations of the events they commemorate but faithful representations of the attitudes of those who built the monuments. What and how we, as a society, choose to commemorate says less about the nobility and honor of the acts and people we are remembering and more about what we find noble and honorable and memorable in those acts and people. Values change as society changes, and our commemorative landscape can act as a time capsule showing us exactly what society deemed important at the moment that the memorial was built. When I went to Gettysburg so I could photograph some of the beautiful commemorative artwork on park grounds, I never anticipated such a clear cut example of this in a small, unobtrusive state monument tucked near where the tour road begins its ascent of Culp’s Hill. Some people who have been following the Confederate monument debate may be surprised, even, that this perfect example of what so many historians have been saying about commemoration and memory is actually a Union monument. I am a Hoosier born and raised, so this is not the first time I have seen the Indiana State Monument. It is the first time, however, I took a close look at the monument. Nearly 13 feet high, the monument features two granite pillars, labeled Liberty and Equality. The central panel features a carved relief of the State Seal of Indiana over the words: Dedicated to those Hoosiers who so nobly advanced freedom on this great battlefield. On the left panel, underneath the Liberty pillar, are the words: In honored memory of those valiant men of Indiana who served in the: 7th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; 14th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; 19th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; 20th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; 27th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; I & K Companies 1st Ind. Vol. Cav. Regt.; ABCDEF Companies 3rd Ind. Vol. Cav. Regt. On the right panel, under the Equality pillar, are the words: On July 1, 1863, Indiana units engaged Confederate forces at Gettysburg and sustained some of the first casualties among the Union ranks. In this battle to preserve the Union, 552 men from Indiana were casualties to that cause. The monument itself sits upon a patio of Indiana limestone and is flanked by two benches where visitors may rest and reflect. There is something on this monument that very specifically dates its creation. Can you find it? To help you, let’s take a closer look at the words used on this monument. The description of the action for the Indiana regiments is an accurate depiction of the battle. The 19th Indiana was one of the five “western” regiments that made up the Iron Brigade, the first Union infantry troops on the battlefield on July 1st. The brigade’s losses were heavy and Gettysburg was essentially the last time that the Iron Brigade was the fearsome, aggressive fighting force that had won its nickname at the Battle of South Mountain in September 1862. The short dedication focuses on advancing freedom with success on the battlefield. After the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863, Washington, D.C.’s war goals were expanded from simply union to union and emancipation. Lincoln echoed the idea of freedom through victory in battle in November of 1863 in his immortal Gettysburg Address. Liberty is defined as the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one’s way of life, behavior or political view. Liberty is one of the key concepts of the Declaration of Independence, the underlying framework for Lincoln’s speech. Equality is mentioned in the Declaration of Independence, too, however, it is a concept relatively anachronistic in the Civil War. Certainly, the words “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” are included by Lincoln in his monumental speech. However, the historical record shows that even in the north, where slavery was outlawed by state constitutions, emancipation did not equal racial equality. This is certainly true in Indiana, where the second version of Indiana’s Constitution, passed in 1851, included Article XIII: Negroes and Mulattoes with the following provisions:

Though Article XIII was removed in 1881, Hoosier soldiers fighting at Gettysburg came from a state that, despite outlawing slavery, was not interested in establishing equality for black freedmen and freedwomen.

The inclusion of the term “equality” however, does give us an idea of when this monument was created. Google N Gram can show us when terms associated with “equality” began to appear in print. The non-qualified word “equality” has been more popular than either “racial equality” or “negro equality”, but the first two terms had notable increases in usage in the 1960s which corresponded to the Civil Rights movement. The term “equality” peaked in usage for the 217 year span beginning in 1800 and ending in 2017 in 1974. A monument designed and built in the immediate aftermath of that societal shift focusing on the attainment of equal rights for blacks, the removal of segregation, and the legal recognition and federal protection of the citizenship rights in the United States Constitution, would certainly look at the Civil War as the first step along the long, circuitous and halting journey toward the equality gained from the Civil Rights Movement. The Civil Rights Movement ended in 1968. The monument was built in 1970.

3 Comments

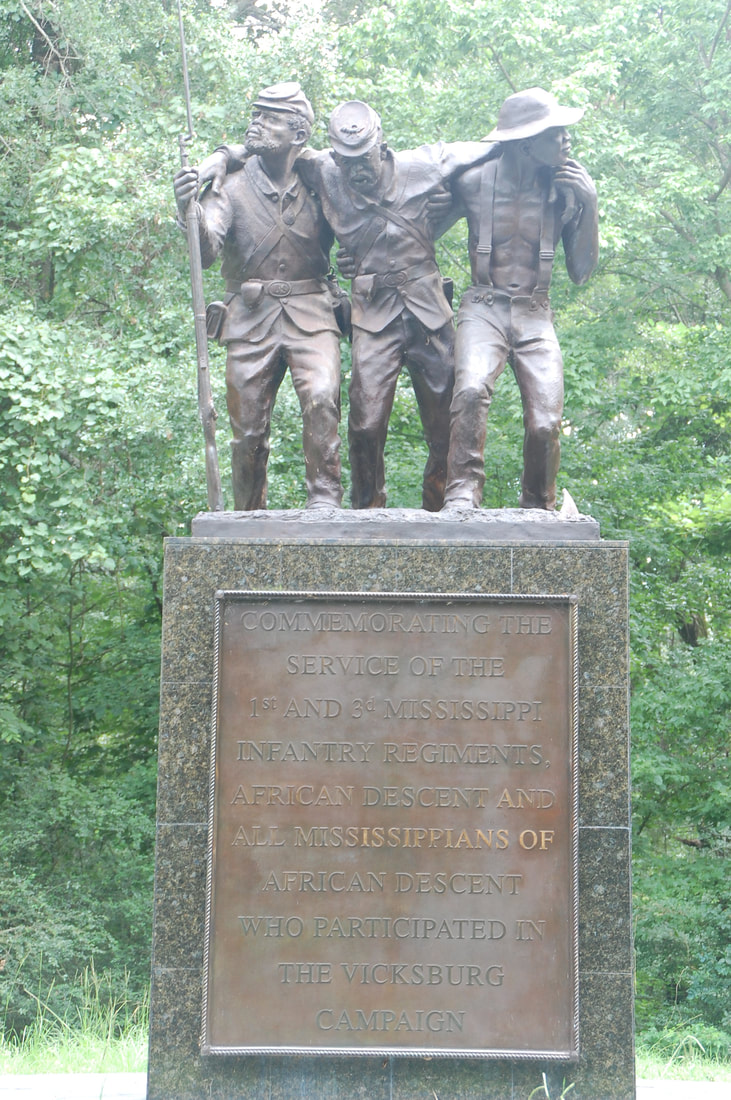

Vicksburg National Military Park is a big place. At over 1,800 acres and a 16 mile tour road, there is no such thing as a quick swing around the park. And while you spend your 45 minutes or more on the winding one-way roads, you will see monuments, markers and tablets. Lots of them. Should you be in the mood to count them all, you will need about a bus load of passengers to count on their fingers and toes. In the event you miss a few—or lose count—the total in the park is over 1,300. Now imagine that Vicksburg is just one of 39 military parks, battlefields and historic sites that feature monuments, tables and historic markers. There are thousands of tributes dotting the landscapes of our Civil War battlefields, and yet it wasn’t until 2004 that a monument dedicated to regiments of African American soldiers was placed on National Park Service land. That monument, the African American Monument in Vicksburg National Military Park, is one of the newest additions to the commemorative landscape. Designed by Brookhaven, Mississippi OB/GYN Dr. J. Kim Sessums, the monument was proposed by Vicksburg Mayor Robert M. Walker in 1999 and commissioned by the State of Mississippi. Its purpose is to commemorate the 1st and 3rd Mississippi Regiments of African Descent, and all African American Mississippians to fight in the Vicksburg campaign, but since it is the first monument of its type in the National Park Service, it also serves as a commemoration of the service of over 178,000 former slaves and freedmen who served in the Union Army and another 18,000 who served in the Union Navy. When asked about the African American contribution to the Union war effort, most people will point to the assault on Fort Wagner by the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, memorialized in the award winning movie Glory. What most people don’t know is that before the 54th Massachusetts gave them hell, United States Colored Troops (USCT) in the Vicksburg campaign proved their mettle in battle at Port Hudson (May 27, 1863) and Millikan’s Bend (June 7, 1863), assuaging the fears of civilian and military leadership in Washington, D.C. about the bravery and fighting ability of the African American troops. It took 141 years for these troops to be commemorated in the way that their contemporaries were being honored all the way back at the beginning of the 20th century. At Vicksburg, the first monument was erected in 1903, and by 1917, 95% of the monuments that currently exist had already been placed. Let’s take a look at one of the park’s newest monuments and see what story the sculptor chose to tell about the African American soldiers who helped take the Confederate bastion of Vicksburg. The base of the monument is polished granite. The bronze plaque on the pedestal reads “Commemorating the 1st and 3d Mississippi Regiments, African Descent and all Mississippians of African descent who participated in the Vicksburg campaign.” The pedestal is topped by three figures. Two soldiers represent the 1st and 3rd Mississippi Regiments, African Descent. The soldier in the center is wounded and is being supported on his left by a field hand, who looks back over his shoulder and on his right by another soldier, who looks forward and upwards. Behind the trio, on the ground, lay a pick and a shovel. This monument uses black African granite, unlike the Mississippi State Memorial which uses white granite quarried from Mount Ary, North Carolina. The African origins of the granite used in the pedestal gives the monument a sense of place and the color draws a direct connection to the African American troops it honors. In a park filled with white granite monuments, including the other monument placed to honor Mississippi troops, the black color is distinctive. Only one other monument, the Connecticut State Memorial, features black granite, and its location is not in the park proper, but in a rarely visited portion of the park located across the river in Louisiana. The center of the three figures, the wounded USCT soldier, represents the sacrifice of blood the 1st and 3rd Mississippi Regiments of African Descent made during the Vicksburg campaign. It represents the struggle of the soldiers' present. Their active participation in combat during this campaign was an important step in winning their own freedom and eventual citizenship. Port Hudson and Milliken’s Bend were trials by fire for the African American troops that participated, but they earned the respect of Union leadership which enabled a transition from providing manual labor to active involvement in the fighting that would secure their status in a new social order. The field hand represents slavery. His glance behind him symbolizes that slavery is in the past. The second soldier is glancing forward, into the future he and his comrade helped to create. His gaze slightly upward indicates this future is filled with hope and promise. Behind the trio lie tools of the past—a pick and a shovel—used by both the slave and the soldiers as they performed as pioneers digging graves, building roads and bridges. They have been abandoned in the pursuit of freedom and the future.

As with all monuments, however, the intended symbolism is just a part of the story. Monuments are imagined and commissioned by people or groups of people to remember things they believe are important. To understand the unintended symbolism, it is important to examine those who are responsible for bringing the monument to life and the societal events that make it possible for the monument to be raised at the time it was. The Vicksburg National Military Park was established in 1899 to protect and memorialize the land on which the siege of Vicksburg took place. By the centennial celebration in 1999, there were still no monuments to the African American troops who had participated in the campaign. The park’s two metal markers commemorating the efforts of members of the African Brigade (or African Descent) came down after 39 years within the park grounds, in 1942. They had been melted down during WWII to help the war effort. Only one recreated tablet returned, and it was consigned to the isolated location of Grant’s Canal in Louisiana. Vicksburg’s mayor, Robert M. Walker, wanted to rectify the oversight. Before being elected, he had been a history professor at several colleges and universities. And when he was elected in 1988 to finish an unexpired term, Robert Walker became Vicksburg’s first African American mayor. He was still in office during the 1999 park centennial and it was his efforts that first broached the subject of installing an African American monument within the military park boundaries. Mayor Walker timed his proposal well. As the park’s centennial approached, and with the critical and box office success of the 1989 movie Glory, the interest in the little told story of nearly 200,000 African American soldiers and sailors increased. Using Google’s Ngram program, we can track the occurrence of certain words and phrases in books over a period of time. We see a marked increase in the occurrence of the term “USCT” in 1987, 1992 and a final jump in 2001, when the term was seven times more frequent than it had been in 1970. The monument, the movie and the increased attention to the 200,000 African American troops that fought in Union blue…all indicate that there was a new societal awareness of, and interest in, non-traditional stories from the Civil War. The placing of this monument at the advent of the 21st century was a long-overdue acknowledgement of the contributions of 9.5% of the total Union army 141 years after the action along the bluff tops above the Mississippi River. I am fond of telling people “Sometimes the green light at the end of the dock just means don’t hit the dock.” (Bonus points if you know what literary classic that references). Some things aren’t meant to be symbolic and the constant need to find meaning in everything can be exhausting. Monuments, on the other hand, are rife with intended and unintended symbolism and they deserve a close examination to really understand the story their commissioners hope to tell. Often times, monuments tell us as much or more about the people who commission and build the monuments than they do about the events and people they commemorate. Being able to read monuments helps place them in the proper historical context. Many Civil War memorials were built after the war, sometimes many decades after. They are primary documents of a post-Civil War age telling us what their commissioners thought important and providing insight into the cultural norms of the commissioners' era. I recently visited Shiloh National Military Park. The park has a variety of memorials and monuments--regimental markers, state monuments and upturned cannon barrels marking the sites of the generals' mortal woundings. One of the most visible monuments is located at tour stop 2--The Confederate Memorial. The monument, created by Frederick C. Hibbard in 1917 was commissioned by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The UDC used a lot of symbolism in this monument, and the National Park Service even includes an explanation of that symbolism on an interpretive marker at the site. Possibly even more interesting are the choices the UDC and the sculptor made in carrying out the symbolism. Both the intended and unintended symbolism deserve a closer look. But before we do that, let's give you a refresher (or an introduction, exceedingly brief though it is) to the Battle of Shiloh as it is important to reading this monument. The Battle of Shiloh was fought on April 6th and 7th, 1862. The first day of battle, the Confederates surprised the Union troops and pressed them from their advanced camps and back along a line close the Pittsburg Landing. Despite the death of Confederate army commander General Albert Sidney Johnston, as the sun set on the evening of April 6th, the Confederate troops and their new commanding general, Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, were confident of a total success the next morning....if only the Union troops stuck around long enough to be destroyed and didn’t retreat under cover of darkness. Even while Beauregard was telegraphing Confederate President Jefferson Davis of a complete victory, Union reinforcements in the form of General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio were being ferried across the Tennessee River and Grant’s lost division under General Lew Wallace was filing into position on the compact defensive line. When the sun rose the next morning, Beauregard discovered Grant and his troops hadn’t run. In fact, they were in a very strong position with fresh troops. The fight on April 7th proved to be the exact opposite of the fighting on April 6th. Union troops pushed the Confederates back and regained the camps they lost the prior day. On the afternoon of April 7th, with his troops exhausted and low on ammunition and food, General Beauregard ordered a general retreat and the Confederates left the field and fell back to Corinth, Mississippi. Knowing how the battle played out, can you identify the symbols of the Confederate story? First, let's take a look at the intentional symbolism the UDC included in this monument. The central bronze figure contains three women. The woman in the front and center is Victory. In her right hand is the laurel wreath of victory. Her head is bowed in defeat and she is relinquishing the laurel wreath to the woman behind and to her right. This woman represents Death. The Death she symbolizes is that of General Albert Sidney Johnston, about whom Jefferson Davis once said, “If Sidney Johnston is no general, then we have no general.” The woman behind Victory to the left is Night. During the battle, the coming of night blunted the momentum of the Confederate advance and brought Union reinforcements. On the left of the monument, the front figure represents the cavalry. His hand is opened in frustration as his horses are not able to penetrate the dense undergrowth on the battlefield. He has no ability to support the Confederate battle plan. Behind him, a representation of the officer corps bows his head at the knowledge that he has been unable to bring a victory. On the right of the monument, a Confederate Infantryman has snatched up the Confederate battle flag in defiance of the Union army and behind him, an artilleryman stands confidently ready for battle. In the limestone, there are several reliefs. The easiest to interpret is the profile at the center of the monument. It belongs to General Johnston and its central location shows the artist's belief in his central role in the battle. After the battle, many of his supporters claimed that had he not been killed, the Confederates would have been able to crush the Union army and may have altered the course of the war. On the right side of the monument, you see the profiles of 11 soldiers, their heads high as they rush like waves into battle. There is one soldier for each Confederate state. They appear confident and courageous. They are marching into battle on April 6th. On the left, those same soldiers’ heads are bowed in disappointment and sorrow. Count them now. There are only 10 left. This is the battle on April 7th. The UDC has used stone and bronze to tell this story: The soldiers of the Confederate States confidently marched into battle under their leader General Albert Sidney Johnston. The Cavalry wasn’t able to support the infantry and artillery because of the dense undergrowth. The artillery and infantry bravely stood up to the Union army, but a sure victory turned into defeat with the death of Johnston and the coming of night that stopped the Confederate momentum and brought Union reinforcements. As the Confederate army retreated, they left many good men behind on the field of battle. That's a lot of symbolism to fit onto a monument its size. But the intended symbolism is only one part of the story. Let's take a second look at the central bronze figure: Victory, Death and Night. As mentioned earlier, the death that is taking the laurel wreath from the hand of Victory is that of General Johnston. Despite the unwavering support Johnston had from Confederate President Jefferson Davis, the Battle of Shiloh was not the apex of his career. Just a few month prior, the defensive line he set up was breached by a joint army-navy expedition that took Forts Henry and Donelson for the Union, leading to the permanent loss of Kentucky and Middle Tennessee including the capital of Nashville. He was being skewered in the press. On the other end of the popularity spectrum was Johnson's nominal second in command, PGT Beauregard, proclaimed the Hero of Fort Sumter and Manassas. He was widely lauded by the press and the populace and many were known to proclaim their excitement that "Bory" had come to town. How did these roles get reversed? Much of it has to do with personal relationships. Davis and Johnston were colleagues and friends with a lot of mutual respect. Davis and Beauregard had a strained relationship partly due to Beauregard's love of crafting grand--and impossibly complicated--strategies. Johnston had the posthumous support of General Braxton Bragg and others (who may have actually been less pro-Johnston than they were anti-Beauregard) who shaped the narrative and Johnston's story was helped along by Johnston's son and aide, Colonel William Preston Johnston, who published his father's biography after the war. Even today, many consider Johnston the presumptive savior of the Confederacy, shot down in his prime. In the same central figure, it is also interesting to note that Night is looking over her shoulder with a furtive glance. Her posture evokes trepidation and nervousness, as if she knows what is coming and is powerless to stop it. Taken with Death, who is taking the laurel wreath from Victory, it evokes a tableau that the victory has been stolen by forces beyond the Confederates' control. Night comes. It is inevitable. Death comes. It is inevitable. And together, two inevitable forces that come each in their own time, take the victory away. It would be unusual for a commissioner to ask for a statue that illustrated ones failures (I have had many failures in my life, and have chosen not to memorialize them), but in the case where they have chosen to erect a Confederate Memorial on a battlefield where the Confederates failed to secure victory, they chose to commemorate the event by symbolically having victory taken from them (rather than being an active participant in their own defeat) by two inevitable, and ultimately neutral, forces--death and night. It is also interesting that the monument is clearly showing the bravery of the individual soldiers. All three of the branches of the army--artillery, infantry and cavalry--are posed with heads high, eager to meet the enemy. Though the cavalry is unable to help, they show frustration, not shame. The one statue with head bowed is representing the officer corps. The officers showed the weakness and bare the shame of the defeat. It is interesting that the central figure alludes to the idea that there was nothing that could be done to stave off the inevitable coming of death and night, but that the officer corps was complicit in the defeat. When added to the intentional symbolism included in the Confederate Monument, it tells the story of not only April 6 and 7, 1862, but of how people of 1917 remembered the battle and the primary players.

There are many ways to appreciate a memorial: as a work of art, as a means to remembering history, and as a way to document the changing interpretations of our history. I realize that sometimes, it is easier and less complicated to simply appreciate a monument for its aesthetic value. Please do so. Monuments can be beautiful creations. My challenge to you is the next time you see a monument, take a moment to read it. See if you can tell what the monument's commissioners intended to say, and what other messages the monument conveys. You will learn about both Civil War history and Civil War memory. |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed