|

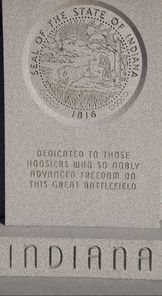

With all of the attention on Confederate monuments recently, I am happy that at least some of the discussion is around the idea that monuments are frequently inaccurate representations of the events they commemorate but faithful representations of the attitudes of those who built the monuments. What and how we, as a society, choose to commemorate says less about the nobility and honor of the acts and people we are remembering and more about what we find noble and honorable and memorable in those acts and people. Values change as society changes, and our commemorative landscape can act as a time capsule showing us exactly what society deemed important at the moment that the memorial was built. When I went to Gettysburg so I could photograph some of the beautiful commemorative artwork on park grounds, I never anticipated such a clear cut example of this in a small, unobtrusive state monument tucked near where the tour road begins its ascent of Culp’s Hill. Some people who have been following the Confederate monument debate may be surprised, even, that this perfect example of what so many historians have been saying about commemoration and memory is actually a Union monument. I am a Hoosier born and raised, so this is not the first time I have seen the Indiana State Monument. It is the first time, however, I took a close look at the monument. Nearly 13 feet high, the monument features two granite pillars, labeled Liberty and Equality. The central panel features a carved relief of the State Seal of Indiana over the words: Dedicated to those Hoosiers who so nobly advanced freedom on this great battlefield. On the left panel, underneath the Liberty pillar, are the words: In honored memory of those valiant men of Indiana who served in the: 7th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; 14th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; 19th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; 20th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; 27th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; I & K Companies 1st Ind. Vol. Cav. Regt.; ABCDEF Companies 3rd Ind. Vol. Cav. Regt. On the right panel, under the Equality pillar, are the words: On July 1, 1863, Indiana units engaged Confederate forces at Gettysburg and sustained some of the first casualties among the Union ranks. In this battle to preserve the Union, 552 men from Indiana were casualties to that cause. The monument itself sits upon a patio of Indiana limestone and is flanked by two benches where visitors may rest and reflect. There is something on this monument that very specifically dates its creation. Can you find it? To help you, let’s take a closer look at the words used on this monument. The description of the action for the Indiana regiments is an accurate depiction of the battle. The 19th Indiana was one of the five “western” regiments that made up the Iron Brigade, the first Union infantry troops on the battlefield on July 1st. The brigade’s losses were heavy and Gettysburg was essentially the last time that the Iron Brigade was the fearsome, aggressive fighting force that had won its nickname at the Battle of South Mountain in September 1862. The short dedication focuses on advancing freedom with success on the battlefield. After the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863, Washington, D.C.’s war goals were expanded from simply union to union and emancipation. Lincoln echoed the idea of freedom through victory in battle in November of 1863 in his immortal Gettysburg Address. Liberty is defined as the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one’s way of life, behavior or political view. Liberty is one of the key concepts of the Declaration of Independence, the underlying framework for Lincoln’s speech. Equality is mentioned in the Declaration of Independence, too, however, it is a concept relatively anachronistic in the Civil War. Certainly, the words “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” are included by Lincoln in his monumental speech. However, the historical record shows that even in the north, where slavery was outlawed by state constitutions, emancipation did not equal racial equality. This is certainly true in Indiana, where the second version of Indiana’s Constitution, passed in 1851, included Article XIII: Negroes and Mulattoes with the following provisions:

Though Article XIII was removed in 1881, Hoosier soldiers fighting at Gettysburg came from a state that, despite outlawing slavery, was not interested in establishing equality for black freedmen and freedwomen.

The inclusion of the term “equality” however, does give us an idea of when this monument was created. Google N Gram can show us when terms associated with “equality” began to appear in print. The non-qualified word “equality” has been more popular than either “racial equality” or “negro equality”, but the first two terms had notable increases in usage in the 1960s which corresponded to the Civil Rights movement. The term “equality” peaked in usage for the 217 year span beginning in 1800 and ending in 2017 in 1974. A monument designed and built in the immediate aftermath of that societal shift focusing on the attainment of equal rights for blacks, the removal of segregation, and the legal recognition and federal protection of the citizenship rights in the United States Constitution, would certainly look at the Civil War as the first step along the long, circuitous and halting journey toward the equality gained from the Civil Rights Movement. The Civil Rights Movement ended in 1968. The monument was built in 1970.

3 Comments

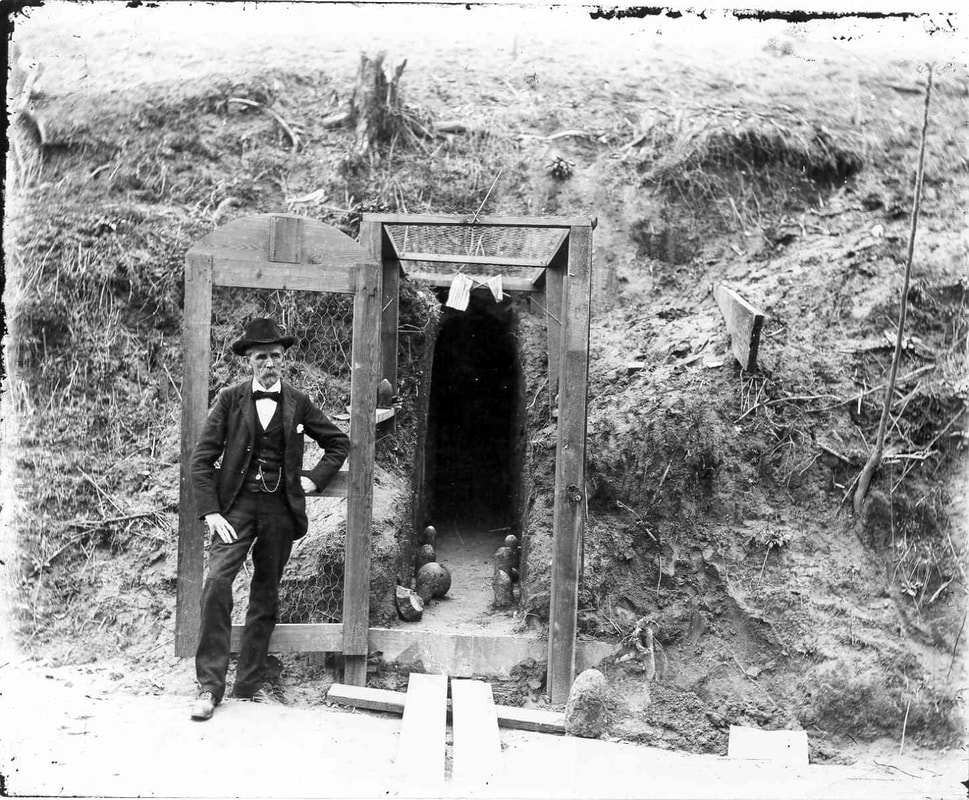

The people of Mississippi had a hard decision to make. For more than a year, the Union forces had attempted to take the clifftop fortress of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River. For more than a year, they had failed. But on the night of April 16, 1863, the Union inland navy under the command of Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, ran the batteries of Vicksburg. As their attempt to sneak by the bluff top cannons under cover of darkness was discovered, the boats hugged the west bank of the river and kept moving as fast as their paddle wheels and the river current could carry them. Every one of the Union ships was hit and sustained damage, but all but one made it. Now, all of the river transports General Grant needed to move his troops from the west bank of the river to the soil of Mississippi were at his command. Soon, the entire Union Army of the Tennessee would be on the road to Vicksburg. The threat of an approaching enemy army forced the area’s citizens to a make a choice. They could stay where they were, far from the protection of the Confederate army and hope that the Union forces would pass them by. If they gambled wrong, they could be subject to humiliation and potential danger as the army moved toward its destination, extending foraging parties along and ahead of the army’s line of march, and trailing stragglers like detritus behind it. Or, they could abandon their property to the tender mercies of the enemy and seek the protection of the Confederate army in the one place they knew the army would be…Vicksburg. Many citizens chose the latter. A month later, after the Union army had defeated the Confederates at Port Gibson, Raymond, Jackson, Champion Hill and Big Black River Bridge, they finally arrived at Vicksburg. Many of the city’s civilians had stayed behind and were joined by those from smaller outlying towns, country farmers and plantation owners. On May 19th, Grant’s army attempted to fight its way into town. It failed. On May 22nd, it tried again. It failed. It was then apparent to Grant this his only option was to “out camp” the Confederates…and consequently all the civilians left within the “protective” embrace of the Confederate trenches. The safety the Mississippians had sought was illusory. The noose began to tighten. The siege had begun. Emma Balfour stayed behind with her husband, a popular physician in town. As the Union army began to surround Vicksburg on May 17, 1863, she was already expressing concern about the city’s fate. “What is to become of all the living things in this place when the boats commence shelling, God only knows. Shut up as in a trap, no ingress or egress, are thousands of women and children who fled here for safety. Then all the mules and horses belonging to this department—and all the stock of all kinds for fifteen or twenty miles around! The Dr. thinks human life will be endangered by the stampede amongst these creatures when terror seizes them. The only comfort is that we can live on them—for I fear we have not provender to feed them for long.” (EB 12-13) Mary Loughborough was one of those fleeing civilians Emma mentioned. On May 19th, as the Union troops attacked the Confederate positions in the trenches encircling Vicksburg, she remembered, “I did not regret my decision to remain, and would have left the town more reluctantly to-day than ever before, for we felt that now, indeed, the whole country was unsafe, and that our only hope of safety lay in Vicksburg. The food shortage both Emma and Mary feared would become real soon enough, but even before then there would be a new, and terrifying form of suffering—the Union gun boats were back. The citizens were stuck between a rock and a hard place. The Union army had formed a semicircular line of trenches anchored on the Mississippi River both north and south of the city. And on the river were gun boats whose cannons were trained on the defensive positions the Confederates held close to town. “At that moment, there was firing all around us, a complete circle from the fortifications above all around us to those below & from the river.” Mary Balfour and the other citizens in Vicksburg were surrounded. (EB 24). Once the guns and the gun boats opened fire, shells began to rain down on the streets of Vicksburg, destroying buildings and striking fear into the civilians—mostly women, children and slaves—who were left in town. People couldn’t sleep or walk outside for fear of a shell bursting and harming or killing them. “The room that I had so lately slept in had been struck by a fragment of a shell during the first night, and a large hole made in the ceiling. I shall never forget my extreme fear during the night, and my utter hopelessness of ever seeing the morning light.” (ML 56) The salvation that many sought would be found just beneath their feet. Vicksburg’s position in the Mississippi River delta country meant that the soil making up the bluffs was an uncommon wind-blown silt and sand mixture known as loess. The flat plate-like grains of this soil make it porous, but not permeable. It is light and soft, but incredibly stable. For the citizens of Vicksburg that meant one thing…caves. Soon after the siege began, the Vicksburg cave construction and real estate markets boomed. Free men and slaves hired out by their owners used shovels to excavate a variety of caves in the soft soil. Some were small and intended for a single family. Others were large and could accommodate several families in separate private quarters with common living spaces and hallways. Lida Lord Reed, the daughter a local minister, and a child of about 11 at the time, described her cave: “Our refuge consisted of five short passages running parallel into the hill, connected by another crossing them at right angles, all about five feet wide, and high enough for a man to stand upright…the people in our cave that night were not counted , but I have heard it stated since that including three wounded soldiers, there must have been at least sixty-five human beings under the clay roof.” (CM 923) Mary Loughborough moved her family into a cave, too. “Our new habitation was an excavation made in the earth, and branching six feet from the entrance, forming a cave in the shape of a T. In one of the wings my bed fitted; the other I used as a kind of a dressing room; in this the earth had been cut down a foot or two below the floor of the main cave; I could stand erect here; and when tired of sitting in other portions of my residence, I bowed myself into it, and stood impassively resting at full height.” (MB 61) The caves were hot, humid, and stinky. Bugs, snakes, and rodents were constant companions, and though many residents brought some comforts of home—furniture, rugs, books—the walls were still dirt, the candle light was dim, and the only privacy they could have in the communal caves was courtesy of blankets hung in dug out doorways. And yet it kept people safer than being above ground, and all for the bargain price of $30 to $50 (about $600 or $1,000 today). (ML 72) It kept people safer, but the cave dwellers were by no means safe. Lucy McRae, another young girl whose family moved into the caves shortly after the siege began, had a close call when a shell exploded directly overhead of her family’s cave. A large chunk of dirt was dislodged by the explosion, burying Lucy. Her mother and their neighbors were frantic, desperately digging with their hands to free the child. In her memoir, Lucy wrote, “The blood was gushing from my nose, eyes, ears and mouth. A physician who was then in the cave was called and said there were no bones broken, but he could not then tell what my internal injuries were.” Lucy would recover. Others would not. (DS 126) “Sitting in the cave, one evening, I heard the most heartrending screams and moans. I was told that a mother had taken a child into a cave about a hundred yards from us; and having laid it on its little bed, as the poor woman believed, in safety, she took her seat near the entrance of the cave. A mortar shell came rushing through the air, and fell with much force, entering the earth above the sleeping child—cutting through into the cave—oh! most horrible sight to the mother—crushing in the upper part of the little sleeping head, and taking away the young innocent life without a look or word of passing love to be treasured in the mother’s heart.” (ML 79-80) As the days wore on, the threat posed by artillery fire continued, and was joined by the prospect of hunger. As food became more scarce, the cave dwellers began to get desperate. Mules were slaughtered and rats were eaten. Even Lida Lord Reed’s beloved pony Cupid, who had accompanied the family to the caves, disappeared, likely a victim of hungry mouths. (CM 927) The civilians weren’t the only ones suffering. In fact, the civilians were arguably comfortable compared to Pemberton’s Confederates, who were now subsisting on quarter rations, enough to keep the nearly immobile army alive…barely. On June 28, Confederate General John Pemberton received a letter signed “Many Soldiers.” “ If you can’t feed us, you had better surrender us, horrible as the idea is, than suffer this noble army to disgrace themselves by desertion. I tell you plainly, men are not going to lie here and perish, if they do love their country dearly. Self-preservation is the first law of nature, and hunger will compel a man to do almost anything. Six days later, on Independence Day, General Pemberton surrendered the city of Vicksburg and his hungry army to General Ulysses S. Grant. The 47 day siege of Vicksburg was now over.

References CM--A Woman's Experiences during the Siege of Vicksburg by Lida Lord Reed The Century Magazine, April 1901, pp. 922-927 DS--The Most Glorious Forth: Vicksburg and Gettysburg, July 4th, 1863 by Duane Schultz. 2002 WW Norton and Company ML--My Cave Life In Vicksburg with Letters of Trial and Travel by Mary Loughborough. 1976 The Reprint Company EB--Mrs. Balfour’s Civil War Diary: A Personal Account of the Siege of Vicksburg by Emma Balfour. 2008 Edited and published by Gordon A Cotton |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed