|

A few weeks ago, I told you about the ironic tale of young Tod Carter who had experienced quite a lot of army life--battle, capture, prisoner of war camp, and a daring escape from a train--only to be mortally wounded a few hundred feet from his family’s home near the center of the Union line at the Battle of Franklin on November 30, 1864.

Nancy Gentry has written a young adult historical novel about the last few days of Tod’s life--beginning her tale on November 29, 1864--and his family’s anticipation of his homecoming. This book is engaging and well written but its main premise, that the family was preparing for an expected homecoming, doesn’t seem to be born out by the facts. Brad Kinnison is a tour guide with the Battle of Franklin Trust, a not for profit preservation organization that now owns and operates several landmarks that played important roles in the Battle of Franklin including Tod’s family home, Carter House. According to Kinnison, the Carter family had no way to know where Tod was at the beginning of the battle. It wasn’t a secret that it was the Army of Tennessee, including Tod's regiment, approaching Franklin, but during his army experience, there had been times when Tod had been detailed for duties away from his unit. One of those times, Tod had escorted prisoners to Virginia. Though the Carter family may have hoped to see Tod, and worried over the possibility of him being engaged in the battle as they huddled in the basement, nothing was confirmed for them until a Confederate soldier found them as they emerged from the basement. He told them that Tod had been wounded and was nearby. I understand why Gentry took this liberty. The Carter Family’s anticipation of the homecoming was fraught with a sense of impending doom. If there had been a soundtrack for this book, much of the first half would have been underscored by the ominous sounds of low brass and timpani rolls. The final culmination is both sad and inevitable. The story uses a few fictional and composite characters to fill out life on the home front. Sarah Beth, Tod’s love interest (in the most PG way), brings a unique perspective to the narrative. She illustrates the often overlooked story of the women left behind after the men go off to war. She is the voice of lost hope for an entire generation of a society where many young men didn’t come back and those who did were damaged by the ravages of war. Gentry uses Sam as a way to insert the slave’s viewpoint into the story. I don’t mind the character’s inclusion, however, whether intentionally or unintentionally, she chooses to ignore factual history in favor of a popular myth that continues to be perpetuated in today’s media (I’m looking at you, Underground). In Gentry’s narrative, Tod’s father, Fountain Branch Carter, “had quietly given all his slaves a written pass to freedom.” Unfortunately for slaves, manumission (granting a slave his or her freedom) was not as simple as giving them a piece of paper as Gentry describes here. According to the 1826 Statute of Laws of Tennessee, the process was much more involved and wouldn’t have been quiet in any regard. Chapter 22 of the Statute outlines that if a slave owner chooses to grant his slaves freedom, he must petition the court. The petitioner (the slave owner) must explain his motives for freeing his slaves and if two thirds of the justices of the county court deem it in the best interest of the state, the petition will be filed with the court. The petitioner was then required to enter into a bond with sufficient financial security to ensure the county would be able to seek recompense from the former slave owner if the newly freed slave caused damages. Given the prevalence of this myth in popular media, I am inclined to believe that she simply didn’t consider that the accepted method of freeing slaves she describes was not factual. While I would have enjoyed a look at the road Tod traveled to make it back to Spring Hill before the book commenced, the book still has enough action to entertain. The pivotal part of the story was told with grace and the dialog is natural and the situations and motivations are, by and large, believable. This is a good book to introduce not only the Battle of Franklin to a young reader, but also to explore timeless themes of honor, duty, family, hope and disappointment. Families can discuss the different reactions between James Cooper (a real person) and Tod Carter upon finding out battle was eminent. They can also discuss Fountain Branch Carter’s options of staying or leaving and what they themselves may have done. Families can explore reasons that freed slaves would stay with their former masters instead of heading North. This is a very readable historical fiction work for young adults, but will get dinged 1 1/2 stars for the lack of historical accuracy and the continued perpetuation of myth.

0 Comments

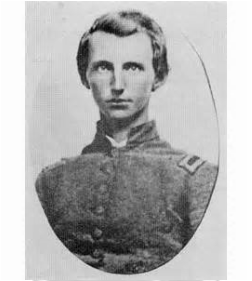

He looks like a child, but by the time the war began, Theodrick “Tod” Carter was 20 years old and a lawyer with a promising future. When Tod’s older brother, Moscow, decided to raise a company of men from around Franklin, Tennessee to support the Confederate war effort, Tod joined what would become Company H of the 20th Tennessee Volunteer Infantry. For more than two years, Tod’s service was largely unremarkable...except for his side gig as a war correspondent for the Chattanooga Daily Rebel under the pen name Mint Julep. All of that changed on November 25, 1863 when Tod’s 20th Tennessee was defending Missionary Ridge outside of Chattanooga. Union General George Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland rushed the commanding Confederate positions high on the mountain ridge overlooking Chattanooga. Confederates abandoned their positions and fled east in a route. At least the lucky ones did. The unlucky ones were dead, wounded or captured. Tod was among the latter.

By this time in the war, both sides had largely given up the rather ineffective policy of paroling captured soldiers---sending them home on their own recognizance with their pledge not to take up arms against the enemy until they had been formally exchanged. Instead, large prisoner of war camps had been established, north and south. Tod Carter was heading for one of those camps, Johnson Island outside of Sandusky, Ohio. Prisoner of war camps were bleak places at best, death traps at worst. But Tod survived Johnson Island and was in the process of being transferred to Point Lookout, another prisoner of war camp, located outside of Baltimore, Maryland, when he escaped from the train transporting him. He was in the wilderness of Pennsylvania, alone and hunted, but Tod was determined to find his unit. He made his way on foot over 600 miles to Dalton, Georgia where he found the 20th Tennessee and rejoined his original unit in the Army of Tennessee. Two months after the fall of Atlanta to Union General William Tecumseh Sherman on September 2, 1864, Sherman set off on his March to the Sea and the Confederate commander of the Army of Tennessee, General John Bell Hood decided to strike at Sherman’s supply line rather than follow him to Savannah. So Hood turned his back on Sherman, and started north to Nashville. Among the soldiers marching north into the Middle Tennessee towns of Columbia and Spring Hill was Captain Tod Carter. He was close to home. Perhaps he had despaired of seeing his family ever again. But in his pocket was a furlough allowing him leave from the army to spend precious little time with his family. Carter House tour guide Brad Kinnison explains that in Franklin, in a small, overcrowded brick house next to the main street leading into town from the south, the Carter family gathered, knowing that Tod’s old unit must be close by. They may have known that Tod wasn’t dead as they had first feared when his horse had returned to the regiment riderless after the Battle of Missionary Ridge, but how could they know that their intrepid son had escaped from a train, and traveled across country to join up with his old unit? On November 30, 1864, Tod Carter was still with his unit when General Hood decided to launch an attack against entrenched Federal forces in Franklin. The large frontal assault was launched against the center of the Union line, which happened to stretch across the land owned by Tod’s father, Fountain Branch Carter. Tod was part of what has been called the Pickett’s Charge of the West. Legend has it that as the 20th Tennessee approached the Union lines dug across the Carter family property, Tod shouted to his comrades, “I’m almost home! Come with me boys!” Only 525 feet from the home in which he grew up, Tod Carter was hit by 9 bullets and lay in the family’s garden severely wounded. After the battle, as the Union troops moved northward toward the safety of the Union garrison at Nashville, Confederate soldiers sought out Fountain Branch Carter to inform him that Tod had been engaged in the battle and had fallen on the family’s property. Tod was brought home and laid in a bedroom just across the hall from the room in which he was born. After a journey of hundreds of miles that stretched to Ohio, Georgia and back to little Franklin, Tennessee, Tod Carter died in the comfort of his family’s bullet ridden home on December 2, 1864 at the age of 24. References Capt. Tod Carter’s Tragic Death, A Life Lost Too Soon Captain Tod Carter |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed