|

A few weeks ago, I told you about the ironic tale of young Tod Carter who had experienced quite a lot of army life--battle, capture, prisoner of war camp, and a daring escape from a train--only to be mortally wounded a few hundred feet from his family’s home near the center of the Union line at the Battle of Franklin on November 30, 1864.

Nancy Gentry has written a young adult historical novel about the last few days of Tod’s life--beginning her tale on November 29, 1864--and his family’s anticipation of his homecoming. This book is engaging and well written but its main premise, that the family was preparing for an expected homecoming, doesn’t seem to be born out by the facts. Brad Kinnison is a tour guide with the Battle of Franklin Trust, a not for profit preservation organization that now owns and operates several landmarks that played important roles in the Battle of Franklin including Tod’s family home, Carter House. According to Kinnison, the Carter family had no way to know where Tod was at the beginning of the battle. It wasn’t a secret that it was the Army of Tennessee, including Tod's regiment, approaching Franklin, but during his army experience, there had been times when Tod had been detailed for duties away from his unit. One of those times, Tod had escorted prisoners to Virginia. Though the Carter family may have hoped to see Tod, and worried over the possibility of him being engaged in the battle as they huddled in the basement, nothing was confirmed for them until a Confederate soldier found them as they emerged from the basement. He told them that Tod had been wounded and was nearby. I understand why Gentry took this liberty. The Carter Family’s anticipation of the homecoming was fraught with a sense of impending doom. If there had been a soundtrack for this book, much of the first half would have been underscored by the ominous sounds of low brass and timpani rolls. The final culmination is both sad and inevitable. The story uses a few fictional and composite characters to fill out life on the home front. Sarah Beth, Tod’s love interest (in the most PG way), brings a unique perspective to the narrative. She illustrates the often overlooked story of the women left behind after the men go off to war. She is the voice of lost hope for an entire generation of a society where many young men didn’t come back and those who did were damaged by the ravages of war. Gentry uses Sam as a way to insert the slave’s viewpoint into the story. I don’t mind the character’s inclusion, however, whether intentionally or unintentionally, she chooses to ignore factual history in favor of a popular myth that continues to be perpetuated in today’s media (I’m looking at you, Underground). In Gentry’s narrative, Tod’s father, Fountain Branch Carter, “had quietly given all his slaves a written pass to freedom.” Unfortunately for slaves, manumission (granting a slave his or her freedom) was not as simple as giving them a piece of paper as Gentry describes here. According to the 1826 Statute of Laws of Tennessee, the process was much more involved and wouldn’t have been quiet in any regard. Chapter 22 of the Statute outlines that if a slave owner chooses to grant his slaves freedom, he must petition the court. The petitioner (the slave owner) must explain his motives for freeing his slaves and if two thirds of the justices of the county court deem it in the best interest of the state, the petition will be filed with the court. The petitioner was then required to enter into a bond with sufficient financial security to ensure the county would be able to seek recompense from the former slave owner if the newly freed slave caused damages. Given the prevalence of this myth in popular media, I am inclined to believe that she simply didn’t consider that the accepted method of freeing slaves she describes was not factual. While I would have enjoyed a look at the road Tod traveled to make it back to Spring Hill before the book commenced, the book still has enough action to entertain. The pivotal part of the story was told with grace and the dialog is natural and the situations and motivations are, by and large, believable. This is a good book to introduce not only the Battle of Franklin to a young reader, but also to explore timeless themes of honor, duty, family, hope and disappointment. Families can discuss the different reactions between James Cooper (a real person) and Tod Carter upon finding out battle was eminent. They can also discuss Fountain Branch Carter’s options of staying or leaving and what they themselves may have done. Families can explore reasons that freed slaves would stay with their former masters instead of heading North. This is a very readable historical fiction work for young adults, but will get dinged 1 1/2 stars for the lack of historical accuracy and the continued perpetuation of myth.

0 Comments

Amos Humiston, Photographer Unknown Amos Humiston, Photographer Unknown This time last year, social media was on the hunt for a man who was photographed dancing at a club. The caption of the photo posted on an internet message board indicated the overweight man had been ridiculed by his fellow club-goers and was embarrassed into stopping. It wasn’t long before the post went viral and the man, a Brit named Sean O’Brien, was identified and invited to a Hollywood dance party organized just for him. The incident showed the power of social media, the ability of a vast network of barely related people to search the globe to find people and bring them together. Sometimes it is hard to remember that this technology is still, in the grand scheme of things, very new. 150 years ago, as the Civil War raged across the country, no one could even imagine the capabilities we have today. Today, anonymity can be difficult. In 1863, it was a possibility that was all too real to the men who fought. In the midst of the Civil War, communication was still relatively primitive. No one was going to be able to post a photo of an anonymous soldier and broadcast it around the world seeking his identity. Because dog tags hadn’t been invented yet and most soldiers hadn’t gotten into the habit of pinning their names and units to their uniforms, many men faced the possibility that their final words and last breath would happen in anonymity, and their bodies would be committed to a final resting place without a name on their headstone. It may have been this fear that ran through Amos Humiston’s mind as he lie dying in a remote portion of the Gettysburg battlefield on July 1, 1863. He had been part of the 154th New York, and his regiment had been positioned on the northeast side of town as the battle commenced. As the Confederates bore down on the town, the 154th New York was overwhelmed and as their line gave way, the soldiers put up a fighting retreat through the streets. The firefight was intense and Amos Humiston was mortally wounded. We cannot know how long he suffered, but we do know that his death was not instantaneous. How? Later in the week, his body was found near the corner of York and Stratton Streets, with an ambrotype of his three children clutched in his hand. That ambrotype was the only identification on him. His unit suffered heavy casualties from the fight and those who survived had already moved on by the time his body was found. Without any identification and no one to vouch for him, his fate as a Unknown Soldier should have been sealed.

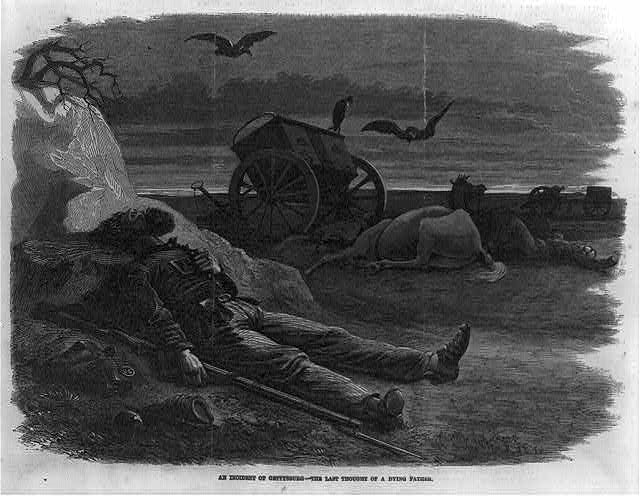

On October 19, 1863, a description of the photograph (photographs could not be reproduced in newspapers of the time) and the circumstances of the soldier’s death, appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer under the headline Whose Father Was He?

"After the battle of Gettysburg, a Union soldier was found in a secluded spot on the battlefield, where, wounded, he had laid himself down to die. In his hands, tightly clasped, was an ambrotype containing the portraits of three small children ... and as he silently gazed upon them his soul passed away. How touching! How solemn! ... It is earnestly desired that all papers in the country will draw attention to the discovery of this picture and its attendant circumstances, so that, if possible, the family of the dead hero may come into possession of it. Of what inestimable value will it be to these children, proving, as it does, that the last thought of their dying father was for them, and them only." Without a photo, the article had to be as descriptive as possible and included notations on clothes (the eldest boy was wearing a shirt of the same material as the girl’s dress), estimated ages (the 9, 7 and 5 were only a year off) and circumstance (the boy in the center is wearing a dark suit and sitting on a chair). Newspapers across the country picked up the story, and on October 29, 1863, Amos Humiston’s wife, Philinda, read this description in a church magazine called American Presbyterian while at her home in Portville, NY. She suspected the description was of her children Frank, Alice and Freddy, but wrote to Dr. Bourns to be sure. He sent her a copy of the ambrotype. When she opened the envelope, all doubt was removed. The anonymous soldier whose last vision before death were the children he loved, had been her husband, Amos Humiston. Amos is buried in Gettysburg National Cemetery. His headstone bears his name. |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed