As a historian and a bibliophile, I have a soft spot in my heart for children’s books that stress famous historic figures’ interest in, and love of, reading. In Words Set Me Free, Lisa Cline-Ransome uses the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave to set the stage for one of Frederick Douglass’s main thematic threads in his autobiography: education was the key to true freedom.

Cline-Ransome begins with the story of Douglass’s early life and chooses some of the most dramatic images from the Narrative to include:

She also uses a portion of Hugh Auld’s declaration to his wife to show the reason that education, in this case the ability to read, would become so important to Douglass: “He should know nothing but to obey his master--to do as he is told to do. If you teach him how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave.” From that moment on, Douglass determines if reading will unfit him to be a slave, then he must learn to read. Cline-Ransome takes us through Douglass’s learning process and how he bartered with and tricked the local boys into teaching him his letters. Even the iconic moment from the Narrative, Douglass’s lamenting over the fact that the ships he watched sail out to see had more freedom than he himself had, makes an appearance in this book. There are a few drawbacks. The language used is easy for adults, but the sentence structure and language may be too complex for younger children. The very first page of the book has two examples: “After I was born, they sent me to my Grandmamma and my Mama to another plantation," and “Cook told me my mother took sick. I never saw her again.” This is not necessarily a bad thing, but be prepared for questions from younger readers. I also dislike the ending of the book. The Epilogue describes Douglass’s first escape attempt in 1835, in which he and several slaves from the plantation tried to escape with forged passes. If you stop reading here--as many would after an Epilogue--and have no more knowledge of Douglass’s story than what is in this book, you would be left with the impression that this escape attempt was successful. It was not. The rest of the story is buried in an Author’s Note on the bibliographical page in the very end of the book. All in all, this is a good introduction to the life of Frederick Douglass for young elementary students, and also provides a historical reference to encourage an interest in, and love of, reading.

0 Comments

If you proclaim an interest in the Civil War, there are a few books that it is assumed you have read. At the top of that list is Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave. One of the best known slave narratives, this autobiographical book packs a big punch in fewer than 100 pages.

At its most basic level, it tells the story of Frederick Douglass’s life in slavery and his escape from it. He details brutality at the hands of some masters and consideration at the hands of others. He tells about times of abundance and times of scarcity. He tells of the tasks he was set to do and those which he chose for himself, often, like his Sabbath School classes, in secret. If this was all that was in this book, it would be enough. But the book also contains a significant amount of subtext that challenges the status quo of Antebellum America. Douglass is a master story teller using classic literature and the Bible to deliver an abolitionist sermon, especially aimed at northern Christians who were turning a blind eye to slavery. In fact, one of the overriding themes of this work is that Christianity is an aggravating factor in slavery, not a mitigating one. The masters who most conspicuously proclaimed themselves Christians were the worst masters. Further, Douglass's subtitle to this work--An American Slave--was, I believe, an intentional choice meant to claim the sin of slavery for the entire nation. Everyone--northerners and southerners, slave holders and free-labor proponents, Christians and non-Christians alike--were complicit in slavery. No one's hands were clean. The impact slavery has on the enslaved is the central theme to many studies of the time, but in the person of Sophia Auld, Douglass illustrates the impact slavery has on the enslavers. When he first meets her, Douglass describes Sophia as “a woman of the kindest heart and finest feelings. She had never had a slave under her control previously to myself, and prior to her marriage she had been dependent upon her own industry for a living.” He claimed to be “astonished by her goodness.” Sophia taught Douglass the alphabet and the rudiments of reading. When her husband, Douglass’s master Hugh Auld, discovered this, he put an immediate stop to it. “If you give a n-- an inch, he will take an ell. A n-- should know nothing but to obey his master--to do as he is told to do. Learning would spoil the best n-- in the world. Now, if you teach that n-- how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanagable and of no value to his master. As to himself, it could do him no good, but a great deal of harm. It would make him discontented and unhappy.” Douglass notes that from that moment on, Sophia Auld began to lose those qualities--piety, warmth, charity and tenderness--that had so thrilled Douglass upon his first meeting her. Her heart grew hard. Douglass even acknowledges, “Slavery proved as injurious to her as it did to me.” Hugh Auld’s lecture to his wife also introduces another central theme: slavery was more than simply bondage of the body. It was bondage of the mind. Douglass understood from that moment on that education was the key to true freedom. Hugh Auld was right. Education would make him discontent and unhappy. Douglass would spend the rest of his childhood as a slave bartering what he could with local boys to get them to teach him to read. When he had nothing to barter, he would dupe those same boys into teaching him by issuing challenges he knew the boys couldn’t ignore. Once he knew how to read, he organized secret Sabbath Schools to help other slaves gain the education that had so discontented Douglass. The original Preface, written by William Lloyd Garrison, can be a barrier. Garrison wrote like someone who liked to hear himself talk. His writing is bombastic in the formal and rather overblown language of orators of the time, and Douglass’s clear and concise writing is a welcome read after the multipage Preface. There are many editions of this book. While the main body’s text will remain the same, some editions provide additional information that will help provide context and further understanding of this deceptively complex work. I read a 1993 edition edited by David Blight. Blight’s footnotes and the supplemental materials highlight the rich literature Douglass drew upon to write his autobiography, and give a glimpse into his subsequent public work. While this particular text is out of print, it can be found used on Amazon and abebooks.com.

Last week, I shared with you the story of Robert Smalls, who made a daring escape from freedom by stealing a boat in Charleston Harbor. The story is exciting and highlights the lengths to which some slaves would go to secure their freedom.

Seven Miles to Freedom tells the story of Robert Smalls from his birth though the successful escape in a format illustrated with beautiful impressionistic paintings. The story starts off with the author drawing the biographical background of Robert’s life on the McKee plantation in Beaufort, South Carolina. Robert tells of the horrors of slavery that he sees on other plantations, but proclaims his master to be good and fair and himself to be treated well. But his personal experience doesn’t temper his hated of slavery. Halfmann introduces us to Hannah, whom Robert falls in love with and marries. The two are lucky in that their masters allow them to live together. When Robert and Hannah’s daughter is born, the two are able to negotiate with Mr. Kingman, Hannah’s owner, for the eventual purchase price of Hannah and their daughter for a sum of $800. To help the couple earn the money, both Mr. Kingman and Robert’s owner, Mr. McKee, allowed them to hire themselves out, and keep all of their earnings but $15 a week paid to Mr. McKee and $7 a week paid to Mr. Kingman. On the verge of having enough to earn his wife’s and daughter’s freedom, the Civil War erupts in nearby Charleston Harbor. Robert reluctantly becomes part of the Confederate war effort as the ship he is the wheelman on, the Planter, is enlisted by the Confederate government to strengthen the harbor defenses by laying mines and destroying lighthouses. One evening, the white crew prepared to leave the boat. Before they left, they jokingly place the captain’s distinctive straw hat on Robert’s head. The simple act is the inspiration for Robert’s daring escape attempt. Halfmann describes the plan. On the next night that the white crew leaves, they will take the boat, pick up their loved ones, and sail out to the Union blockade, with Robert posing as the ship’s captain, straw hat and all. If they are caught, everyone agrees they will sink the boat and if the process takes too long, they will hold hands and jump overboard to drown themselves. They refuse to go back to a life of bondage. Halfmann’s strength is in the narration of the escape attempt. The rather slow and ordinary beginning of the book hits its stride when Robert’s plan is executed. I am always impressed by authors who are able to achieve suspense when its readers know (or can easily find out ) how the story actually ends. Halfmann succeeds here, creating a “hold your breath” moment as Robert slides the ship past Fort Sumter as the sun rises and his cover could be blown. This book works on several levels. First, it is an engaging story on the surface. Who doesn’t love a good, suspenseful escape from bondage story that allows you to cheer at the end? Second, for older children, the way Halfmann writes provides great opportunities to discuss the meaning of freedom:

There is some rather archaic language, as the author chooses to use the word “colored” on several occasions. This can be a bit of a shock for a book published in 2008. And I take a bit of exception to the idea that Robert knew, in 1861 , that a Union victory in the Civil War meant the abolition of slavery. At that time in the war, that conclusion could not be drawn, as the federal government was fighting for Union. Lincoln, after issuing the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September of 1862, used the carrot of retained slavery to entice the recalcitrant Confederate states back into the Union before the Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863. Had any slave state chosen to return to the Union prior to that date, slavery would have been protected as it continued to be in the Union-loyal slave holding border states. Intelligence Report--Cadets At War: The True Story of Teenage Heroism at the Battle of New Market1/25/2017

Earlier this week, I shared the story of the VMI Cadets' coming of age. On May 15, 1864, 257 cadets from the Virginia Military Institute ranging in age from 15 to 19 years old put their military training to the test. For many of these cadets, this was the first time in a live combat situation. They were supposed to be the reserve of the Confederate Army operating under General Breckinridge. After a Confederate regiment from Missouri was cut to pieces, General Breckinridge gave the order he dreaded: “Put the boys in, and may God forgive me for the order.”

This book from Susan Provost Beller looks at personal letters and cadet files in the VMI archives to give a voice to that small number of cadets who helped the Confederates turn the tide of the battle. Beller begins with providing a bit of background, takes us with the cadets as they march north (“down the valley”) toward New Market, advance around the Bushong Farm House and through a muddy field (the Field of Lost Shoes) and finally as they defend their honor in the press and public perception years after the guns have gone silent. The book is less than 100 pages long, so the background on the cadets and the battle is necessarily brief. The battle scenes have urgency and don’t get bogged down in lots of minutia. Beller’s use of the words and stories of only a few of the cadets gives the book focus. However, the maps are hand drawn and difficult to read. The illustrations, with the exception of the cadet photos, did not reproduce well. Both maps and illustrations fail to adequately support the text. The writing style is very casual; the author writes how I imagine she speaks. She mentioned in the introduction she has shared this story with school groups many times, and it sounds as if she simply provided a transcription of one of those presentations. It is probably beneficial for young readers, but for me, it lacked authority. One final thing that that is only incidental to the story but that bothers me enough to correct--or perhaps better explain--why going north through the Shenandoah Valley is actually “down the valley” while going south is “up the valley.” She gives a vague reason tied to Pennsylvania settlers moving south away from civilization and into the unknown, so they called it going “up the valley.” The real answer is much more concrete and even simpler: the Shenandoah River flows from south to north toward its confluence with the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry, WV. Therefore going south is going upriver—up the valley—and going north is going downriver—down the valley. It almost makes me call into question all of the research she did for this book. Thankfully, she quoted letters and official records enough that the voices of the cadets are authentic. Earlier this week, I shared with you the story of Johnny Clem. The nine-year old earned fame for things he did and things he probably didn’t do. Called both “Johnny Shiloh” and “The Drummer Boy of Chickamauga”, Johnny survived the Civil War and later in his life went on to have a second distinguished career in the United States Army

Johnny’s story is the subject of John Lincoln Clem: Civil War Drummer Boy. This is a work of historical fiction and author E.F. Abbott has done a wonderful job creating an engaging, book-length story for young readers. The main character, Johnny Clem himself, is a well-written multidimensional character. He is stubborn and defiant, but honorable. He has a moment of cowardice and resolves to be brave. He is good but flawed. He is someone you want to root for. The author weaves in a lot of vignettes about camp life for ordinary soldiers including the rampant disease that would claim more lives than bullets did. She even uses a well documented description of General Grant-- “He wore an expression as if he had decided to drive his head through a brick wall and was about to do it.” The battle scenes are realistic and urgent and don’t romanticize what was truly a confused and terrifying experience. As a piece of fiction, this book is top notch. Unfortunately, the author’s research on her subject seems spotty. As I noted in my previous post, it is highly unlikely that Johnny was ever at Shiloh. The 3rd Ohio, the regiment he unofficially joined in this book did not fight at Shiloh and the 22nd Michigan, the regiment that he eventually formally enlisted with, was not mustered in until August 1862, several months after the battle of Shiloh. Several times, the author refers to beating the long roll as a call to advance. The long roll was actually a call used to call the soldiers to arms. It was to get the troops’ attention and get them all in one place so that a subsequent order could be sounded. It was not beat throughout an advance or to announce a charge. An additional concern appears when Captain McDougal asks the assembled crowd the reason the Confederate states seceded. The crowd answers “slavery” and McDougal adds a whole bunch of other things that are another way of saying slavery including economics and states’ rights and throws in the tariff for good measure. Captain McDougal tries to lessen the impact slavery had on the Confederacy’s founding, which does a disservice to the actual history. To add insult to injury, officers of the rank Captain are in command of a company of approximately 100 soldiers, not entire regiments (until later in the war when casualties began to mount). Regiments were commanded by Colonels. Because of the strong fictional narrative, I still highly recommend this book despite the historical liberties taken. In fact, the inaccuracies provide an opportunity to research some primary documents in a critical manner.

John Lincoln Clem: Civil War Drummer Boy is a great way to introduce the role of children in combat with an engaging and fast moving story so long as it is understood to be historical fiction.

I don’t usually read two books at one time, but as the departure date of our Charleston vacation quickly approached, I had to make an exception. I haven’t known the remarkable story of the Hunley for long, but I knew it was woven into the fabric of its adopted home town of Charleston and made visiting it a top priority. Like pretty much every other historical site I visit, I like to prepare with a little homework to help me understand what it was I was going to see. I had two books I wanted to read--one focusing on the history of the submarine and the other focusing on the modern search and recovery--and only time to read one.

Between trying to clear my desk of urgent work for my day job, keeping up with Drummer Boy and the general running of the household, I could only dedicate half an hour or so during the evening, some days per week to reading. The only other time I had to dedicate to reading was my commute. But even as a passenger, reading while in a car would not translate to a particularly good time for me or anyone in my general proximity. As a solo driver with over an hour commute each way several days a week, reading while driving is not...encouraged. Thank goodness for Audible, the only safe way to read while driving (unless, I suppose you have hired a professional narrator that travels with you every where you go). I listened to Tom Chaffin's book on my way to and from work and work appointments and read Hicks and Kropf's book while curled up into the corner of my couch after Drummer Boy finally agreed to close his eyes. Reading both at virtually the same time allowed me to compare and contrast the two books much more easily as most of the information remained fresh in my mind while the authors crafted their own explanations and tried to use their sources to back their positions. It was an unwitting debate between the authors, and I got to judge the best position. The H.L. Hunley: The Secret Hope of the Confederacy was primarily focused on the history of submarine development, putting the Confederate efforts--including the CSS Pioneer and the American Diver--in historical context. Chaffin also used his time to illuminate the back story of the men who would propel the technology forward. Two-thirds of his book focused on the time leading up to the sinking of the Hunley, and only the final third focused on the aftermath. Ultimately, Chaffin only dedicated the final three chapters to the search for, and recovery of, the Hunley. Raising the Hunley: The Remarkable History and Recovery of the Lost Confederate Submarine by Brian Hicks and Schuyler Kropf is a story mainly of the efforts to find and then recover the Hunley. There is a discussion about the history of the submarine and its predecessors, but only the first third of the book covers this, leaving the authors, local Charleston journalists who were eye witnesses to the recovery and early conservation of the craft, lots of time to tell you exactly what they saw. So, which book should you read? Readability In The H.L. Hunley, there are several times Tom Chaffin uses $5 words when nickel words would do. Some of those times actually caused me to roll my eyes, their use was so out of place (dare I say egregious) within the structure of the sentence they were used in, it seemed an obvious effort to show off a superior vocabulary just because he could. While most of his text is highly readable, it is likely that you will learn a few new words to add to into your not-so-everyday conversations. Raising the Hunley is written by journalists and the reading level reflects this. Hicks and Kropf do not dumb things down, but they keep the language easy and the reading flows well. It is descriptive but not challenging. Winner: Raising the Hunley Credibility of the Authors Tom Chaffin uses his introduction to explain his method of historic research. He focuses on using primary documents and when he cannot document, he clearly identifies his own use of speculation. One of the best ways to see his extensive use of historic record is how he debunks the widely accepted myth that Queenie Bennett both gave George Dixon his famous gold coin and that she was his sweetheart. Hicks and Kropf’s eyewitness status to the raising and recovery of the Hunley notwithstanding, their sourcing is generally secondary documents (documents written by people who were not participants or contemporaries of those participants living at the time). Winner: The H.L. Hunley Overall Quality of the Work Chaffin’s book was published in 2008. It is a careful and thoughtful treatment of the history of the Hunley. His sources are credible, and he carefully discloses the rare instances of author speculation. Though there are some sections that are a bit dry and more academic, it isn’t something that plagues the whole of the book. Published in 2002, Hicks' and Kropf’s book reads like they rushed to write and publish it to take advantage of a transient public interest that would soon fade. Besides their unquestioning adherence to the Queenie Bennett myth, they also retell the story of the blue light from the lantern that was the prearranged sign to alert the crew’s home base on Sullivan Island that they had been successful, going so far as to cite the archaeologists’ find of the submarine’s lantern still inside the submarine as proof. They leave out, however, that the lantern’s lenses were clear and that there is no indication that they were ever tinted blue. Had they waited for more of the excavation of submarine, and allowed the findings to drive their narrative, rather than the other way around, the book would have improved greatly. Winner: The H.L. Hunley These are not the only books available on the Hunley, and I picked up several others while I was at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, including a newer work by Brian Hicks published in 2014 which may correct some of the errors of his prior work. But until my schedule and reading list allow, people who wish to learn more about the sad tale of the remarkable men and their submarine won’t go wrong picking up or listening to Tom Chaffin’s The H.L. Hunley: The Secret Hope of the Confederacy.

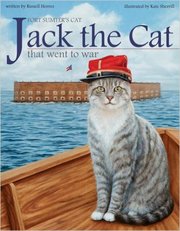

Drummer Boy is looking forward to his vacation in Charleston, South Carolina next month. I like reading ahead when I visit a battlefield or historic site. It helps me better appreciate where I am visiting. It also helps ratchet up the anticipation for an upcoming visit. So, I went looking for a book to read to Drummer Boy that introduces Charleston’s Civil War history in a way that is entertaining for a 4 year old. That is when I made the acquaintance of a “most unusual cat.”

Jack, the son of Miss Kitty and Mr. Tom, lives with the Rhett family in Charleston. He witnesses the initial bombardment of Fort Sumter before Colonel Rhett decides to take this self-proclaimed Confederate cat to the fort itself to help the soldiers control the mice eating their food stores and the birds polluting their drinking water. Readers learn about the layout of the fort, its Confederate occupation, bombardment by Union naval forces, and the lives of the Confederates inside the fort’s walls. Jack’s story is based on oral tradition and period illustrations that indicate that a garrison cat existed at Fort Sumter. The book also contains actual documented historic events and figures who were important to the city and fort’s history. It is an effective blending of fantasy and fact to create a memorable story. One of the big challenges with all children’s Civil War books--especially picture books-- is presenting the information in a way that honors the history in an age appropriate way without sugarcoating it. Many books like this struggle integrating slavery and the reality of the antebellum South in a way that doesn’t minimize the former and glorify the latter. Russell Horres strikes the right balance as he spends all of one page describing Jack’s antebellum life, accompanied by Kate Sherrill’s beautiful misty depiction of hoop skirts, oak tree avenues and a columned Great House. But he also introduces Mauma June, a slave who describes her abduction from her family in Africa, her sense of loss and the limits to her freedom. In a particularly telling moment, she admits to Jack that she is envious of him—the family pet—because of his freedom. The book is text heavy, but each page is accompanied by beautiful illustrations that bring Jack to life, help illustrate the charm of Charleston and highlight the insular world of life in such a small, isolated fort. The final pages provide an illustrated Glossary of Terms that helps both the children and any adults reading to them build their vocabulary. This book was written in 2011 for the sesquicentennial (150th anniversary) of the first shorts of the Civil War. It is no longer in print, but new and used copies are available through Amazon's third party sellers and other used book vendors. Click on the book's title in this post to see the new and used offers on Amazon. Intelligence Report--Allegiance: Fort Sumter, Charleston and the Beginning of the Civil War8/6/2016

The first shots of the Civil War were fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 12, 1861. It was the beginning of a war, the scope of which was beyond the general citizenry’s imagination. This wasn’t only a beginning, but the ending of months of political and diplomatic failures that highlighted just how unprepared everyone was for the fight about to commence.

David Detzer’s Allegiance: Fort Sumter, Charleston and the Beginning of the Civil War examines both the beginnings and endings that took place in and around Charleston during the Secession Winter of 1860 and the following spring that resulted in the fateful cannon shot that started the war. Our cast of “characters” include:

It takes a special author to create suspense and a sense of urgency in a story of which we know the ending. Detzer does this. Even though we know that the Confederates fire on Fort Sumter, as we watch the calendar pages turn, the deft maneuvering by Union Major Robert Anderson, and the desperate incompetence of President Buchanan produce moments of frustration and disbelief for the reader. Detzer paints Anderson as a man who is trying his best and being misunderstood at every turn. It doesn’t help that he has little to no political or military support aside from vague orders and non-specific encouragement. Further complicating issues is the fact that South Carolina is determined to see Anderson’s actions as coercion intended to force a military engagement despite the actions being taken deliberately intended to deescalate tensions to the extent his vague orders allowed. There were so many times in the months between South Carolina’s declaration of secession and the bombardment of Sumter that could have initiated war (firing on of the Star of the West and the clumsy and comical efforts of the captain of the ship Shannon) that the ending seemed inevitable. We are only left wondering exactly when the fuse would burn up and the powder keg blow. It is important to note that only the final two chapters deal with the actual bombardment of Fort Sumter. It is a compelling part of the story, but it is the easiest and most straightforward part. The bulk of this book is about politics and diplomacy and the failures and success of each, which makes this more of a political thriller than a military history. This book is a great introduction into the messy politics of revolt, revolution and the start of a civil war. It reads like a novel, with well drawn characters you will care about. A great book for mature readers interested in how this kind of conflict starts, and those who love a good novel of political intrigue.

When Drummer Boy was 2, I wanted to supplement his library with history picture books. While on one of my trips to a battlefield (though I don’t remember which one), I picked up a picture book about the Civil War that had everything I was looking for: beautiful illustrations, great Civil War topics and a way for me to teach him the alphabet.

The topics addressed in B is for Battle Cry are very broad—Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis are discussed alongside disease, the role of quartermasters and prisons for captured soldiers—and add a level of depth and context that will make this interesting for older readers and parents as well as children just learning their alphabet. For me, the meter of the verses was a little bit difficult to navigate. It never seemed to quite roll of the tongue while I was reading it aloud. I believe the reason for this is the verses were written to be sung to the tune of Stephen Foster’s Hard Times Come Again No More. Don’t be worried if you, like me, were not immediately familiar with this incredibly popular song from the mid-nineteenth century. To help you out, the author, Patricia Bauer, sings her verses to the accompaniment of her acoustic guitar in a free download available on her illustrator husband’s website. The four line alphabet verses are supplemented by sidebars that give older readers and parents more explanation of the topics addressed. Though “T is for Trains,” its side bar discusses the new and emerging technology like telegraphs, rifle muskets and the Gatlin gun, that leads many historians to consider the Civil War the first modern war. And while “Y is for Yankee” Johnny Reb is mentioned as the counterpoint to Billy Yank and the author describes the families who were torn apart by divided loyalties. Overall, this is a great introduction to the Civil War for young readers and little ones who like to be read to. For the full experience, try singing the verses and see how it transforms story time. Buy your own copy of B is for Battle Cry: A Civil War Alphabet. |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed