|

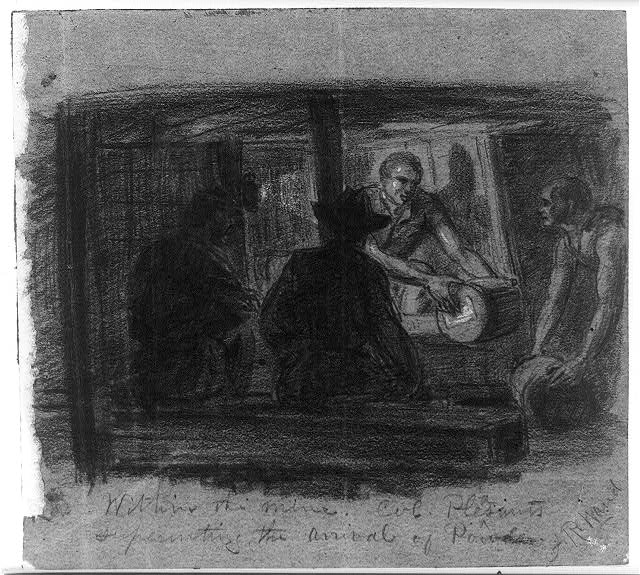

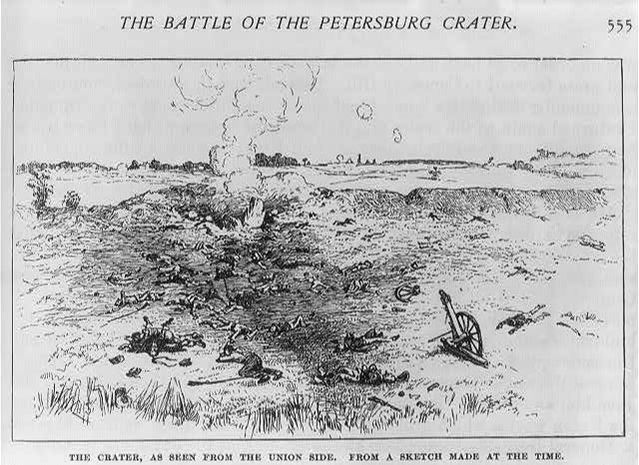

At 4:44 in the morning of July 30, 1864, a low rumble emanated from the ground under Elliot’s Salient, a fortified bump in the Confederate defensive lines around Petersburg, Virginia. Moments later, the earth seemed to heave up, up, up. The sky over the Confederate line was filled with dirt, smoke, splintered wood and bodies. As the shower of debris fell back to the ground after its ascent of hundreds of feet, it buried alive many men who had just moments before been sleeping within their lines. The explosion of the mine dug by Pennsylvania coal miners of the 48th Pennsylvania was just the beginning of the short and pitched battle that General Ulysses S. Grant would later call “the saddest affair I have witnessed in this war.” What may be even sadder than the death and destruction that the battle wrought was that the entire enterprise--the digging and springing of a mine under the Confederate position and the attack that followed--was an attempt to shorten the war and minimize further bloodshed. Done right, it may have worked. As General Ambrose Burnside originally planned, the men of the Fourth Division of his IX Corps, under the command of General Edward Ferrero were to move toward the breach in the Confederate lines caused by the explosion. Two units, one on each side of the assaulting column, were to wheel to their right and left as they reached the line, covering the flanks of the attack and widening the breach for the second and third wave of troops to enter. The movement was intricate and the men were inexperienced, but they spent two weeks training and on the eve of the explosion, they were ready. There was only one problem…the units of the Fourth Division were all regiments of United States Colored Troops (USCT). Where the upper brass—Generals Grant and George Meade—had acted with apathy toward the plan since its inception, on the very eve of the planned detonation of the mine, they now took an active role that would severely damage the plan’s chances of success. Fearing that a failure of the mission spearheaded with African American troops would create a political backlash and charges of intentionally squandering African American lives, they denied Burnside the troops he needed most to be successful. He had deliberately chosen the Fourth Division because his other units had been fought out. They had had nearly 40 days of constant contact with the Confederates--some of the most violent days of the war--and now were suffering from both physical and emotional fatigue. The USCT, however, had been used mostly on fatigue duty, out of contact with the enemy. They were anxious for the chance to prove themselves capable fighters. Now, Burnside was forced to choose between his three worn down and worn out divisions who had not been trained for the intricate maneuvers and the confusion that would reign after the explosion of the mine. And to choose this very important role? He chose to draw straws. The winner (or perhaps more accurately, the loser) was General James Ledlie, a habitual drunk. Either he did not or could not convey Burnside’s orders for the plan of attack, the most important part of which was the objective: Cemetery Hill (or Cemetery Ridge) directly behind the Confederate line. They were to go around the crater resulting from the mine explosion. The lack of orders prior to the attack may have been mitigated had Ledlie been with his men to lead them in their attack, but Ledlie spent the majority of the day behind the Union lines, safe in a bomb-proof (bomb shelter), drinking “stimulants” (rum).

When the men of Ledlie’s First Division stepped off minutes after the explosion, they headed straight into the hole. There they were caught like fish in a barrel and as the supporting divisions came in behind, including the final division in line, the Fourth Division of USCT, they continued to crowd into the deep depression with steep and crumbling sides. As the Confederates shook off the shock and rushed troops to the breech, the crater became a roiling mass of panicking men who became easy targets. Some of Burnside’s troops, and others from a Division of General OC Ord’s XVIII Corps were able to skirt the crater, but they then entered a labyrinth of defensive trenches that curtailed their movement and made them vulnerable to enfilading fire on their flanks. The fighting here and in the crater devolved into hand to hand combat, with rifles being wielded as clubs and bayonets thrust into soft bellies of the enemy. Even within this chaos, the Union still had an opportunity to succeed. The constant flow of Confederate support to the crater had seriously weakened Confederate lines in front of General Gouverneur K. Warren’s V Corps. Warren asked General Meade, his commanding officer, if he should proceed to attack what he perceived as a weak spot in the Confederate line in front of him. Meade, out of touch with the actual chaos happening on the battlefield, misinterpreted Burnside’s tepid observation that an attack on Warren’s front could achieve a breakthrough and rout the enemy. Instead of ordering Warren’s Corps to attack, Meade stayed Warren and told Burnside to withdraw his troops. Burnside was unable to withdraw his troops without exposing them to deadly crossfire, but they were equally unable to stay in the pit and the trenches. Burnside hedged his bets and commanded his troops to stay put until they could retreat under cover of night. It was only early afternoon. As it turns out, the engaged troops decided when to withdraw or surrender. And many of the USCT troops who chose the latter were murdered in the attempt. When the Union troops finally withdrew, the Confederates reclaimed the crater, reestablishing the line they held prior to the explosion. In their attempts to shore up the new line, their excavations uncovered comrades who had been buried alive by the debris of the blast. The Battle of the Crater, as the engagement became known, had nearly 15,000 Union troops either committed to the attack itself or deployed along the Union lines near the crater. 504 were killed or mortally wounded; 1,881 wounded; 1,413 captured. Of the four divisions engaged in the attack, the Fourth Division—the USCT troops who had been specially trained and later pulled from their position at the point of attack for fear of a public relations nightmare—suffered the highest casualty count anyway: 1,327. One final victim of the Battle of the Crater was General Ambrose Burnside, who was found by the US Army Court of Inquiry (convened at the behest of General Meade) to be largely culpable for the debacle. He was later removed from command of the Ninth Army Corps. Though an investigation by the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War largely vindicated him when it published its findings in February 1865, he would never hold command again. References and Further Reading The Horrid Pit: The Battle of the Crater, the Civil War’s Cruelest Mission The Crater

0 Comments

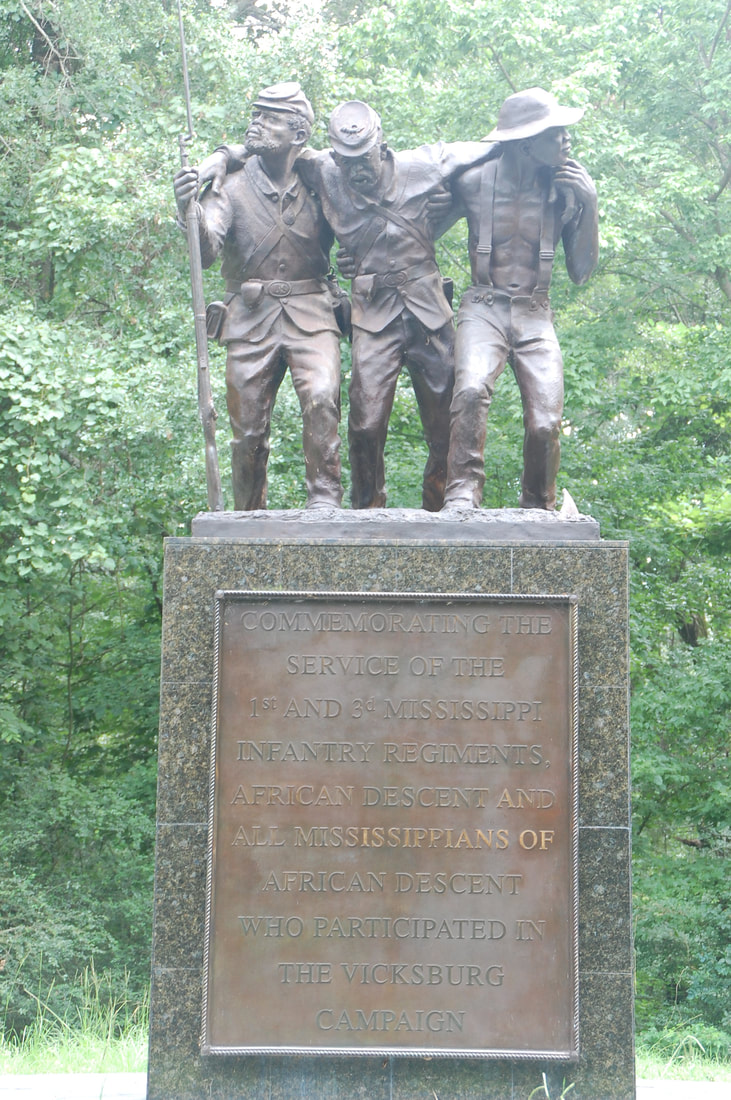

Vicksburg National Military Park is a big place. At over 1,800 acres and a 16 mile tour road, there is no such thing as a quick swing around the park. And while you spend your 45 minutes or more on the winding one-way roads, you will see monuments, markers and tablets. Lots of them. Should you be in the mood to count them all, you will need about a bus load of passengers to count on their fingers and toes. In the event you miss a few—or lose count—the total in the park is over 1,300. Now imagine that Vicksburg is just one of 39 military parks, battlefields and historic sites that feature monuments, tables and historic markers. There are thousands of tributes dotting the landscapes of our Civil War battlefields, and yet it wasn’t until 2004 that a monument dedicated to regiments of African American soldiers was placed on National Park Service land. That monument, the African American Monument in Vicksburg National Military Park, is one of the newest additions to the commemorative landscape. Designed by Brookhaven, Mississippi OB/GYN Dr. J. Kim Sessums, the monument was proposed by Vicksburg Mayor Robert M. Walker in 1999 and commissioned by the State of Mississippi. Its purpose is to commemorate the 1st and 3rd Mississippi Regiments of African Descent, and all African American Mississippians to fight in the Vicksburg campaign, but since it is the first monument of its type in the National Park Service, it also serves as a commemoration of the service of over 178,000 former slaves and freedmen who served in the Union Army and another 18,000 who served in the Union Navy. When asked about the African American contribution to the Union war effort, most people will point to the assault on Fort Wagner by the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, memorialized in the award winning movie Glory. What most people don’t know is that before the 54th Massachusetts gave them hell, United States Colored Troops (USCT) in the Vicksburg campaign proved their mettle in battle at Port Hudson (May 27, 1863) and Millikan’s Bend (June 7, 1863), assuaging the fears of civilian and military leadership in Washington, D.C. about the bravery and fighting ability of the African American troops. It took 141 years for these troops to be commemorated in the way that their contemporaries were being honored all the way back at the beginning of the 20th century. At Vicksburg, the first monument was erected in 1903, and by 1917, 95% of the monuments that currently exist had already been placed. Let’s take a look at one of the park’s newest monuments and see what story the sculptor chose to tell about the African American soldiers who helped take the Confederate bastion of Vicksburg. The base of the monument is polished granite. The bronze plaque on the pedestal reads “Commemorating the 1st and 3d Mississippi Regiments, African Descent and all Mississippians of African descent who participated in the Vicksburg campaign.” The pedestal is topped by three figures. Two soldiers represent the 1st and 3rd Mississippi Regiments, African Descent. The soldier in the center is wounded and is being supported on his left by a field hand, who looks back over his shoulder and on his right by another soldier, who looks forward and upwards. Behind the trio, on the ground, lay a pick and a shovel. This monument uses black African granite, unlike the Mississippi State Memorial which uses white granite quarried from Mount Ary, North Carolina. The African origins of the granite used in the pedestal gives the monument a sense of place and the color draws a direct connection to the African American troops it honors. In a park filled with white granite monuments, including the other monument placed to honor Mississippi troops, the black color is distinctive. Only one other monument, the Connecticut State Memorial, features black granite, and its location is not in the park proper, but in a rarely visited portion of the park located across the river in Louisiana. The center of the three figures, the wounded USCT soldier, represents the sacrifice of blood the 1st and 3rd Mississippi Regiments of African Descent made during the Vicksburg campaign. It represents the struggle of the soldiers' present. Their active participation in combat during this campaign was an important step in winning their own freedom and eventual citizenship. Port Hudson and Milliken’s Bend were trials by fire for the African American troops that participated, but they earned the respect of Union leadership which enabled a transition from providing manual labor to active involvement in the fighting that would secure their status in a new social order. The field hand represents slavery. His glance behind him symbolizes that slavery is in the past. The second soldier is glancing forward, into the future he and his comrade helped to create. His gaze slightly upward indicates this future is filled with hope and promise. Behind the trio lie tools of the past—a pick and a shovel—used by both the slave and the soldiers as they performed as pioneers digging graves, building roads and bridges. They have been abandoned in the pursuit of freedom and the future.

As with all monuments, however, the intended symbolism is just a part of the story. Monuments are imagined and commissioned by people or groups of people to remember things they believe are important. To understand the unintended symbolism, it is important to examine those who are responsible for bringing the monument to life and the societal events that make it possible for the monument to be raised at the time it was. The Vicksburg National Military Park was established in 1899 to protect and memorialize the land on which the siege of Vicksburg took place. By the centennial celebration in 1999, there were still no monuments to the African American troops who had participated in the campaign. The park’s two metal markers commemorating the efforts of members of the African Brigade (or African Descent) came down after 39 years within the park grounds, in 1942. They had been melted down during WWII to help the war effort. Only one recreated tablet returned, and it was consigned to the isolated location of Grant’s Canal in Louisiana. Vicksburg’s mayor, Robert M. Walker, wanted to rectify the oversight. Before being elected, he had been a history professor at several colleges and universities. And when he was elected in 1988 to finish an unexpired term, Robert Walker became Vicksburg’s first African American mayor. He was still in office during the 1999 park centennial and it was his efforts that first broached the subject of installing an African American monument within the military park boundaries. Mayor Walker timed his proposal well. As the park’s centennial approached, and with the critical and box office success of the 1989 movie Glory, the interest in the little told story of nearly 200,000 African American soldiers and sailors increased. Using Google’s Ngram program, we can track the occurrence of certain words and phrases in books over a period of time. We see a marked increase in the occurrence of the term “USCT” in 1987, 1992 and a final jump in 2001, when the term was seven times more frequent than it had been in 1970. The monument, the movie and the increased attention to the 200,000 African American troops that fought in Union blue…all indicate that there was a new societal awareness of, and interest in, non-traditional stories from the Civil War. The placing of this monument at the advent of the 21st century was a long-overdue acknowledgement of the contributions of 9.5% of the total Union army 141 years after the action along the bluff tops above the Mississippi River. |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed