Intelligence Report--Behind Rebel Lines: The Incredible Story of Emma Edmonds, Civil War Spy3/30/2017

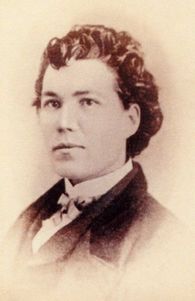

As an action hero, Sarah Emma Edmonds is the Lara Croft of the Civil War. Assuming the identity of the male soldier Franklin “Frank” Thompson, she joined the Union Army in 1861 as a battlefield nurse, and spent time as a courier before taking on the role of Union spy. If young women of your acquaintance need a historical role model, they could certainly do worse than Sarah Emma Edmonds.

Behind Rebel Lines has been on my reading list for longer than Civil War Scout has existed. I have been anticipating this fictionalized version of Edmonds’ story, but in the end, it didn’t live up to my (perhaps too lofty) expectations. At just under 150 pages, this is a relatively short book, and as such, it doesn’t provide more than a few pages of context to explain Edmonds’ adopting a male persona even before her time in the Union Army. This results in a rather flat character who is driven by vague, unspecified motivations usually attributed to an “imp voice”. Unfortunately, this motivation is confusing for several reasons:

This book was originally written in 1991 and has been republished several times. The language and stereotypes may be a bit jarring, especially when Edmonds takes on the personas and dress of others as she is inserts herself in her spy career, but I suspect that much of that comes directly from her memoirs and is indicative of the contemporary accounts during the Civil War. Though it is on my (extensive) reading list, I have yet to read Edmonds’ memoirs Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, so I can’t judge how faithfully the narrative follows the original memoirs, but I can confirm that the soldier Allen Hall, whom Edmonds discovered on one of her espionage missions, does show up on the muster rolls of the 25th Virginia Infantry which fought at Gaines Mill (also known as the First Battle of Cold Harbor), so it does lead credence to the veracity of the story. Until I have a chance to read the source documentation (or what the author claims as his source documentation), I will categorize this as historical fiction. A great companion to this book is the History Channel’s Full Metal Corset: Secret Soldiers of the Civil War which introduces Edmonds with more background and fleshes out her personality and her history.

1 Comment

I wanted to save my posts for this Women’s History Month to highlight the lesser known contributions of women to the war effort. The soldiers, spies, and healers who defied traditional gender roles and took action to effect the course of the war instead of letting the war happen to them. At first glance, Sarah Morgan, a 19 year old young woman living in Baton Rouge with her family when the war started, may not exactly fit the bill. Though she never donned a uniform, or slipped secrets of the enemy’s whereabouts to her army’s commanders, Sarah Morgan’s candid writing made her one of the best known diarists of Civil War America and her words have helped countless generations understand the ravages of the war on the southern home front.

Sarah Morgan’s published diary, The Civil War Diary of a Southern Woman, measures 615 pages and spans a time period from January 10, 1861 through June 15, 1865. A tome of that size might prove intimidating for an adult, so, author Debra West Smith decided to make it more accessible to a middle school audience. By editing the source volume and creating dialog from the material, Smith has crafted an engaging, and largely faithful recreation of Morgan’s diary. The key to Sarah’s relevance is that she observed life from a young woman’s point of view, and much of it was emotional and visceral writing. That comes through in Smith’s adaptation and enhances the value of such a book to engender critical thinking and discussions with middle school students or family members. One of Sarah’s earliest revelations is that the Union soldiers are not the monsters that prevailing sentiment claimed them to be. Sarah, feeling defiant with her friends, wears a homemade Confederate national flag pinned to her shirt when she goes to the State House. There she unexpectedly sees fifteen to twenty Union soldiers standing on a terrace, being watched like animals. Sarah says she is ashamed that she drew attention to herself, and claims she felt humiliated and conspicuous. At first, she lays the blame for her feelings on the idea that she has not been ladylike in her behavior. Just one paragraph later, she reveals the true issue…she hadn’t expected the Yankees to be such gentlemen--fine and noble looking “showing refinement and gentlemanly bearing.” Sarah’s later interactions with the occupying Union force shows her earlier revelation about the Yankees drives her actions--taking food to the injured Union troops because she acknowledges that they have loved ones at home. She also hopes that someone would do the same for her brothers fighting with the Confederate forces. Her revelation that she can be compassionate to men who wear another uniform and not compromise her loyalty to her brothers and her cause is described as doing the right thing, and is a lesson appropriate today. There are some really good discussion opportunities for families and classes to discuss attitudes of slaveholders and how they perceive the motivations of their slaves as is evidenced in the passage in which Sarah watches the Linwood “servants” (Sarah uses “servants” much more frequently in her diary than she uses “slaves”) laughing in the sugar house while the master’s young guests play games and try their hands at stirring the boiling kettles of sugar. Smith’s Sarah says “It occurred to her that if Abe Lincoln could spend grinding season on the plantation he would recall his Proclamation. Never in her home, nor at Linwood, had she seen the cruelty abolitionists railed about, and the dark faces that joined her silly songs seemed far from miserable.” In her diary, Sarah Morgan includes a lament of the same nature on November 9, 1862: “ And to think, Old Abe wants to deprive us of all that fun. No more cotton, sugar cane, or rice! No more old black aunties or uncles! No more rides in mule teams, no more songs in the cane field, no more steaming kettles, no more black faces and shining teeth around the furnace fires! “If Lincoln could spend the grinding season on a plantation, he would recall his proclamation. As it is, he has only proved himself a fool, without injuring us. Why last evening I took old Wilson’s place at the baggasse shoot, and kept the rollers free from cane until I had thrown down enough to fill several carts, and had my hands as black as his. What cruelty to the slaves! And black Frank things me cruel too, when he meets me with a patronizing grin, and shows me the nicest vats of candy, and peels cane for me! Oh! Very cruel! And so does Jules, when he wipes the handle of his paddle on his apron, to give ‘Mamselle’ a chance to skim the kettles and learn how to work! Yes! And so do all the rest who meet us with a courtesy and ‘Howd’y young missus!” This scene raises questions such as:

“I am going away to the Great House Farm! O, yea! O, yea! O!” This they would sing, as a chorus, to words which to many would seem unmeaning jargon, but which, nevertheless, were full of meaning to themselves. I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do. I did not, when a slave, understand the deep meaning of those rude and apparently incoherent songs. I was myself within the circle; so that I neither saw nor heard as those without might see and hear. They told a tale of woe which was then altogether beyond my feeble comprehension; they were tones loud, long, and deep; they breathed the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains. The hearing of those wild notes always depressed my spirit, and filled me with ineffable sadness. I have frequently found myself in tears while hearing them.” Since the text of Sarah Morgan: The Civil War Diary of a Southern Woman is available online, advanced readers can verify Smith’s version of events by checking it directly with the source material as they read along. The only thing that keeps this from being a 5 star book is some confusing writing that results in Sarah’s mother magically appearing in the story several times without explanation. She was miles away and suddenly, there she is, back at the house in Baton Rouge or ministering to wounded soldiers in Sarah’s presence after she has tearfully taken her goodbyes and moved away. It is likely this is the result of the heavy editing required to trim 600 pages to 173 pages, and the excluded material probably helps with context, but more careful editing could have avoided these issues entirely.

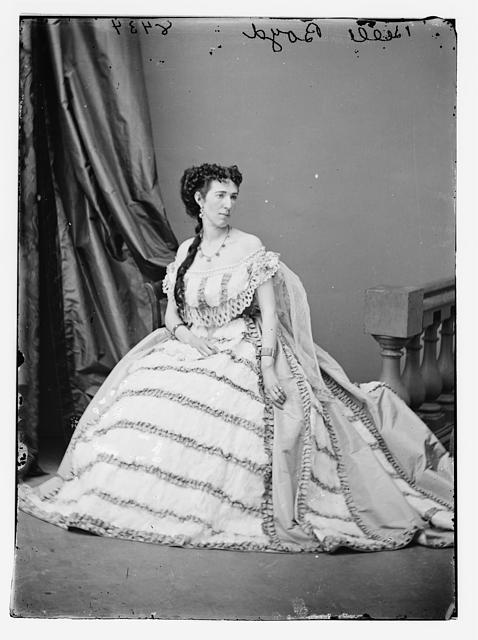

Unlike many of the families in the area of Virginia the Boyds lived (which was so against secession that it broke from Virginia to create the Union-loyal state of West Virginia), the Boyds had deep southern roots and supported the cause of the Confederacy. Belle’s father volunteered for a Virginia infantry regiment which was commanded by Colonel Thomas Jackson before he had earned his famous nickname for standing like a stone wall. After a skirmish between Confederate and Union forces at the Battle of Falling Waters, just 8 1/2 miles north of the Boyds’ home, Union forces came through Martinsburg. One of the Federal soldiers entered the Boyd home and confronted Belle’s mother. Belle would not tolerate the disrespectful and harassing language and behavior. She shot the man. The Union officer sent to investigate determined that Belle had been in the right and she escaped punishment. Belle was not considered beautiful, but because she was tall, vivacious, well-dressed and young, she was able to charm unsuspecting Union officers into revealing information which she would then pass to the Confederates through her neighbor or her slave. Eventually, she became an official operative for Generals PGT Beauregard and Stonewall Jackson. In May 1862, after having been detained by Union forces, she was at her aunt’s home near Fort Royal. The home was now the headquarters of Union General James Shields, who was on a mission to whip Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley. The General called a Council of War--a meeting with his subordinates to set a course of action--held in her aunt’s drawing room. On the second floor, directly above the drawing room was a closet. And in the floor of the closet was a hole. Belle gathered her intelligence while in the cramped closet, then when the Council ended at 1 a.m., she set out for Confederate lines on horseback, her pockets holding cast off passes for Confederate heading south. The papers fooled the sentries, and she was able to get her information to Confederate cavalryman Colonel Turner Ashby. On May 23rd, Jackson’s men approached Front Royal. Belle had more valuable information that she believed could ensure a victory for the Confederate forces. She knew the size and disposition of Union forces in the lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley. Though she approached several men who had professed Confederate sympathies to carry the information to Jackson, none agreed to do so. So she went herself. Belle’s escape from the Union lines was harrowing, with Federal picket fire hitting the ground near enough to spray dirt in her eyes and other Union bullets tearing holes in her dress. When she was safely behind Confederate lines she was greeted by Jackson’s aide Henry Kyd Douglass who recognized her and took her notes to Jackson himself. Jackson was so grateful for her daring that he wrote her a note of thanks: May 23d 1862 Miss Belle Boyd, I thank you for myself and for the army, for the immense service that you have rendered your country today. Hastily I am your friend, T.J. Jackson, O.S.A Only two months later, Belle was captured and imprisoned at Old Capitol Prison on Washington, D.C. She spent a month there before being exchanged. She went back to her career in espionage and again, she was capture and imprisoned, this time for five months. After her release the second time, she was banished to the south, but instead of retiring, she simply decided on a change of base, and set sail for England. While enroute, her ship was stopped by the Union navy and again, she was arrested as a spy. Belle went on to captivate one of her Union captors, Samuel Hardinge, who she hoped to convert to the Confederate cause. Whether his loyalty to his country was compromised or simply his heart, he did serve time for giving aide to Belle.

References and Further Reading

Maria "Belle" Boyd Belle Boyd Biography Belle Boyd in Camp and Prison by Belle Boyd  Sarah Emma Edmonds Sarah Emma Edmonds When you think of a Civil War soldier, what image comes to mind? Perhaps a young man, thin and haggard, wearing tattered butternut. Maybe a middle aged African American soldier wearing blue for the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Maybe you think about a little boy, wearing a drum across his small body or a bugle over his shoulder. No matter what image pops into your mind, chances are the soldier you are picturing is male. According to the Civil War Trust, over 3 million soldiers fought during the Civil War and the vast majority of those soldiers were men as neither the Union nor Confederate army had a policy allowing the enlistment of female soldiers. But as many as 400 women fought regardless, serving in Union and Confederate uniforms during the war. One of those dressed in Union blue, Sarah Emma Edmonds, left behind a memoir detailing her history, and though historians are skeptical of some of her claims, what is verified fact about her life shows a woman not content to sit on the sidelines while her adopted country fought its defining war. Sarah Emma Edmonds was an American by choice. She was born in the province of Nova Scotia, Canada in December in 1841. Her father was disappointed she was not a boy, and she spent much of her young life trying to prove to him her worth. Eventually, seeing the futility of her efforts, she fled from her father’s oppression and an arranged marriage, first to New Brunswick, and later, to put more distance between herself and her father, she immigrated to the United States. She did so in disguise, adopting the persona of a young man named Franklin Thompson. She had established herself as a traveling Bible and bookseller, first in Connecticut, and later outside of Flint, Michigan where she was living when the Confederates opened fire on Fort Sumter and President Lincoln issued his call for 75,000 troops to suppress the rebellion. Edmonds decided it was time to fight for her new country.

She disguised herself as black male “contraband” named “Cuff” performing manual labor for the Confederate army.

She drew on her experience as a traveling book seller to pose as an Irish peddler woman named “Bridget O’Shea” selling goods to Confederate soldiers behind enemy lines. She donned black face and a red bandanna and while working as a washer woman, came across a packet of official papers that had been in a Confederate officers’ uniform jacket. Her unit was transferred several times, and it eventually ended up in the western theater, where Edmonds continued her work as a spy, and then as a nurse. It was here, while she was tending wounded and ill soldiers, that she contracted malaria in 1863. Afraid her secret would be discovered if she were treated by the army surgeons, she requested a furlough. When it was denied, she left her unit for treatment. Franklin Thompson was declared a deserter and Edmonds’ military career was at an end. Even while the war still raged, she wrote her memoirs titled Nurse and Spy in the Union Army, the first edition of which was published in 1864. She donated the money she earned from book sales to various soldiers’ causes. When the 2nd Michigan held a reunion in 1876, her former comrades in arms welcomed her warmly and took up the cause of removing the blight of “desertion” from Franklin Thompson’s military record, which led to Edmonds being able to receive a military pension in 1884. In 1897, she joined the Grand Army of the Republic, the fraternal organization of Union Civil War veterans. She was the only woman ever to do so. After the war, Edmonds married and had three children. She moved to Texas with her family and died in 1898. She was buried with military honors in Washington Cemetery in Houston. References and Further Reading Sarah Emma Edmonds, Private Sarah Emma Edmonds Biography Memoirs of a Soldier, Nurse and Spy: A Woman’s Adventure in the Union Army by Sarah Emma Edmonds

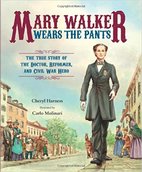

Children who see women dressed in pants and shorts these days may not understand how unusual the practice was in the past. Nor may they understand that being a female doctor in the mid-19th century was unusual. But both of these things, and others, make Mary Walker a unique woman. Mary Walker Wears the Pants is a picture book that looks at all the ways Mary Walker was different and the way society treated her because of it.

She was a courageous woman whose parents had encouraged independent thinking. That led her to embrace a movement called “dress reform” trying to change the norm of restrictive clothing women were expected to wear. She believed in women’s suffrage and equal civil rights for men and women. And author Cheryl Harness shows that she was whispered about and ridiculed for her choices. The story quickly gets to Dr. Walker’s service during the Civil War in which she volunteered as a nurse, was finally accepted as an official Assistant Surgeon, and was captured and became a prisoner of war. Harness then explains the awarding of the Medal of Honor and her post-war career. Harness does not explain the controversy which resulted in the rescission of Dr. Walker’s Medal of Honor in 1917 or its later reinstatement. Dr. Mary Walker’s story is exciting and appealing, and Harness does a capable job of telling her story. Harness does frame much of Dr. Walker’s experiences around her choice of clothing, and the theme is never really distant. At points, it seems as though Harness is trying to promote this as the most unusual thing about Dr. Walker’s extraordinary life. Unfortunately, this seems to be done at the expense of more thorough discussion of her medical school experience and her career as an army surgeon. I will give the author the benefit of the doubt in the latter, however, as it is not easy to find an age appropriate way to address the blood and gore of a field hospital. It also at least provides a framework for other discussions including how people treat others who dress differently or make unconventional choices for their life. Harness certainly paints Dr. Walker as a capable, dedicated and persistent surgeon who encouraged rethinking many previously held ideas including gender roles and traditional medical treatment in combat situations. This is a great book for girls and boys to be introduced to a little known, but important, female hero of the Civil War (and the country’s only female Medal of Honor winner).

By the time the Civil War broke out, Walker had already experienced the ups and downs of life. She graduated from Syracuse Medical School in Syracuse, New York in 1855. She had married, set up a private practice, closed that same private practice, and divorced her husband. She had embraced the idea of dress reform, raising eyebrows and eliciting whispers because of her decision to avoid the constricting, uncomfortable and unhealthy clothing women were expected to wear—long skirts, petticoats, and corsets—instead dressing in men’s pants and suspenders worn under short dresses. As the country mobilized after President Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the Confederate rebellion, Dr. Walker tried to join the army, but much like society at large, the United States Army was skeptical of the skills of a female surgeon. Instead, Mary volunteered her time as a nurse, bandaging wounds, comforting the sick and wounded, writing letters for soldiers who couldn’t do so themselves. Near Washington, D.C. as the first battle of the Civil War got underway just miles outside of town near Bull Run Creek, she worked in a field hospital caring for the battle’s Union wounded. She later worked at the Patent Office Hospital, served as an unpaid field surgeon after the Union defeat at Fredericksburg and in Chattanooga after the Union defeat at Chickamauga. Though the Army wouldn’t enlist her, they finally began to employ her as a contracted (civilian) Assistant Surgeon for the Army of the Cumberland. She would later be appointed Assistant Surgeon of the 52nd Ohio Infantry Regiment. On April 10, 1864, she had just finished assisting a Confederate surgeon with an amputation, when Confederate troops captured her in neutral territory and accused her of spying. Dr. Walker was transported to Castle Thunder, a prisoner of war camp in Richmond, Virginia, where she spent the next four months. Her dress, which allowed her the freedom of movement necessary to perform her duties as an army surgeon, was especially conspicuous in Castle Thunder and brought ridicule in the Richmond newspapers, including the Richmond Sentinel, which reported in its April 22, 1864 edition, “Female Yankee Surgeon--The female Yankee surgeon captured by our pickets a short time since, in the neighborhood of the army of Tennessee, was received in this city yesterday evening, and sent to the Castle in charge of a detective. Her appearance on the street in full male costume, with the exception of a gipsey hat, created quite an excitement amongst the idle negroes and boys who followed and surrounded her. She gave her name as Dr. Mary E. Walker, and declared that she had been captured on neutral ground. She was dressed in black pants and black or dark talma or paletot. She was consigned to the female ward of Castle Thunder, there being no accommodations at the Libby for prisoners of her sex. We must not omit to add that she is ugly and skinny, and apparently above thirty years of age.” She was finally exchanged, surgeon for surgeon, on August 12, 1864. She returned to her service and was given charge of female prisoners in a Kentucky prison and later a Tennessee orphanage. After the war, Generals William Tecumseh Sherman and George Thomas recommended Dr. Walker for the Medal of Honor and on November 11, 1865, President Andrew Johnson signed the order awarding her the Army’s highest honor even though she had served as a civilian. Whereas it appears from official reports that Dr. Mary E. Walker, a graduate of medicine, "has rendered valuable service to the Government, and her efforts have been earnest and untiring in a variety of ways," and that she was assigned to duty and served as an assistant surgeon in charge of female prisoners at Louisville, Ky., upon the recommendation of Major-Generals Sherman and Thomas, and faithfully served as contract surgeon in the service of the United States, and has devoted herself with much patriotic zeal to the sick and wounded soldiers, both in the field and hospitals, to the detriment of her own health, and has also endured hardships as a prisoner of war four months in a Southern prison while acting as contract surgeon; and Whereas by reason of her not being a commissioned officer in the military service, a brevet or honorary rank cannot, under existing laws, be conferred upon her; and Whereas in the opinion of the President an honorable recognition of her services and sufferings should be made. It is ordered, That a testimonial thereof shall be hereby made and given to the said Dr. Mary E. Walker, and that the usual medal of honor for meritorious services be given her.

This month, in honor of Women’s History Month, we will explore how women redefined their roles in society by entering traditionally male worlds during the most trying time of the county’s history.

|

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed