Shiloh National Cemetery, Pittsburg Landing, TN April 2016 Shiloh National Cemetery, Pittsburg Landing, TN April 2016 The Civil War created death on a larger scale than had ever been seen before in the history of the young country. The generally accepted number of 620,000 dead from battle wounds, complications and disease has been challenged with recent scholarship that suggests the number may be closer to 750,000. Even the conservative number exceeded the total number of dead in prior wars (20,978) by more than an astounding 29 times. The deaths accounted for nearly 2% of the country's total population. To put that into perspective, if the same percentage of the country's total population today were killed, that would amount to 6,473,000 lives lost. One of the ways that the Civil War has shaped who we are today is in the way we, as a nation, deal with death. Fittingly for today, one of the summer's most popular three day weekend holiday's--Memorial Day-- came about as a way for people to remember the northern dead who had lost their lives in the service to their country during the Civil War. Former Union General, John "Blackjack" Logan, as the national commander of the Union veteran fraternal organization, the Grand Army of the Republic, issued an order on May 5, 1868 proclaiming May 30 as a day to decorate Civil War graves with flowers. The celebration, originally called Decoration Day, became a national holiday in 1967. While Decoration Day helped a wounded country emotionally deal with the grand scale of death, the country couldn’t wait three years after the war to address the physical issues associated with the death the war created. In July 1862, Congress authorized President Abraham Lincoln to purchase land for the creation of cemeteries for “soldiers who shall have died in the service of the country.” That year, 14 National Cemeteries were created, including one in the tiny town of Sharpsburg, Maryland, where 4,476 Union soldiers were buried after the battles in Maryland. Antietam, the most famous, became (and remains) the bloodiest day in American history with 3,650 Americans dead (by contrast, 2,499 Americans died in Operation Overlord on D-Day). There are currently 136 National Cemeteries across the country. Most are administered by the Veterans' Administration, but 14 are administered by the National Park Service as part of Civil War battlefields and historic sites and two (including Arlington) are still administered by the Army. Almost every battlefield I have been to has a National Cemetery on the battlefield or nearby. It is a highlight of my visit to stroll among the quiet headstones, reading names and giving thanks. Almost uniformly, these parks are quiet, solemn places of rest for Civil War veterans and others from the area who died in combat. Some, like the cemeteries at Shiloh and Fredericksburg, provide scenic views. Others, like Gettysburg, were the site of other historic action. At every national cemetery I've visited, I've been greeted by low black metal markers lining the sidewalks. The words, painted in white, present a fitting tribute to those who lie nearby in eternal repose. The verse contained on the markers is Bivouac of the Dead, written by Kentuckian Theodore O'Hara in honor of his fellow Kentuckians who died at the Battle of Buena Vista in the Mexican American War. Though most of the National Cemeteries only include a few select verses, the poem in its entirety is a fitting way to remember all of the men who fell during the Civil War, and in all American wars before and since. The muffled drum's sad roll has beat

The soldier's last tattoo; No more on Life's parade shall meet That brave and fallen few. On fame's eternal camping ground Their silent tents to spread, And glory guards, with solemn round The bivouac of the dead. No rumor of the foe's advance Now swells upon the wind; Nor troubled thought at midnight haunts Of loved ones left behind; No vision of the morrow's strife The warrior's dreams alarms; No braying horn or screaming fife At dawn shall call to arms. Their shriveled swords are red with rust, Their plumed heads are bowed, Their haughty banner, trailed in dust, Is now their martial shroud. And plenteous funeral tears have washed The red stains from each brow, And the proud forms, by battle gashed Are free from anguish now. The neighing troop, the flashing blade, The bugle's stirring blast, The charge, the dreadful cannonade, The din and shout, are past; Nor war's wild note, nor glory's peal Shall thrill with fierce delight Those breasts that nevermore may feel The rapture of the fight. Like the fierce Northern hurricane That sweeps the great plateau, Flushed with triumph, yet to gain, Come down the serried foe, Who heard the thunder of the fray Break o'er the field beneath, Knew the watchword of the day Was "Victory or death!" Long had the doubtful conflict raged O'er all that stricken plain, For never fiercer fight had waged The vengeful blood of Spain; And still the storm of battle blew, Still swelled the glory tide; Not long, our stout old Chieftain knew, Such odds his strength could bide. Twas in that hour his stern command Called to a martyr's grave The flower of his beloved land, The nation's flag to save. By rivers of their father's gore His first-born laurels grew, And well he deemed the sons would pour Their lives for glory too. For many a mother's breath has swept O'er Angostura's plain -- And long the pitying sky has wept Above its moldered slain. The raven's scream, or eagle's flight, Or shepherd's pensive lay, Alone awakes each sullen height That frowned o'er that dread fray. Sons of the Dark and Bloody Ground Ye must not slumber there, Where stranger steps and tongues resound Along the heedless air. Your own proud land's heroic soil Shall be your fitter grave; She claims from war his richest spoil -- The ashes of her brave. Thus 'neath their parent turf they rest, Far from the gory field, Borne to a Spartan mother's breast On many a bloody shield; The sunshine of their native sky Smiles sadly on them here, And kindred eyes and hearts watch by The heroes sepulcher. Rest on embalmed and sainted dead! Dear as the blood ye gave; No impious footstep here shall tread The herbage of your grave; Nor shall your glory be forgot While Fame her record keeps, For honor points the hallowed spot Where valor proudly sleeps. Yon marble minstrel's voiceless stone In deathless song shall tell, When many a vanquished ago has flown, The story how ye fell; Nor wreck, nor change, nor winter's blight, Nor time's remorseless doom, Can dim one ray of glory's light That gilds your deathless tomb. Bivouac of the Dead Theodore O'Hara

0 Comments

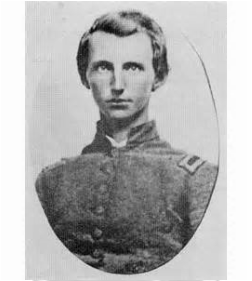

He looks like a child, but by the time the war began, Theodrick “Tod” Carter was 20 years old and a lawyer with a promising future. When Tod’s older brother, Moscow, decided to raise a company of men from around Franklin, Tennessee to support the Confederate war effort, Tod joined what would become Company H of the 20th Tennessee Volunteer Infantry. For more than two years, Tod’s service was largely unremarkable...except for his side gig as a war correspondent for the Chattanooga Daily Rebel under the pen name Mint Julep. All of that changed on November 25, 1863 when Tod’s 20th Tennessee was defending Missionary Ridge outside of Chattanooga. Union General George Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland rushed the commanding Confederate positions high on the mountain ridge overlooking Chattanooga. Confederates abandoned their positions and fled east in a route. At least the lucky ones did. The unlucky ones were dead, wounded or captured. Tod was among the latter.

By this time in the war, both sides had largely given up the rather ineffective policy of paroling captured soldiers---sending them home on their own recognizance with their pledge not to take up arms against the enemy until they had been formally exchanged. Instead, large prisoner of war camps had been established, north and south. Tod Carter was heading for one of those camps, Johnson Island outside of Sandusky, Ohio. Prisoner of war camps were bleak places at best, death traps at worst. But Tod survived Johnson Island and was in the process of being transferred to Point Lookout, another prisoner of war camp, located outside of Baltimore, Maryland, when he escaped from the train transporting him. He was in the wilderness of Pennsylvania, alone and hunted, but Tod was determined to find his unit. He made his way on foot over 600 miles to Dalton, Georgia where he found the 20th Tennessee and rejoined his original unit in the Army of Tennessee. Two months after the fall of Atlanta to Union General William Tecumseh Sherman on September 2, 1864, Sherman set off on his March to the Sea and the Confederate commander of the Army of Tennessee, General John Bell Hood decided to strike at Sherman’s supply line rather than follow him to Savannah. So Hood turned his back on Sherman, and started north to Nashville. Among the soldiers marching north into the Middle Tennessee towns of Columbia and Spring Hill was Captain Tod Carter. He was close to home. Perhaps he had despaired of seeing his family ever again. But in his pocket was a furlough allowing him leave from the army to spend precious little time with his family. Carter House tour guide Brad Kinnison explains that in Franklin, in a small, overcrowded brick house next to the main street leading into town from the south, the Carter family gathered, knowing that Tod’s old unit must be close by. They may have known that Tod wasn’t dead as they had first feared when his horse had returned to the regiment riderless after the Battle of Missionary Ridge, but how could they know that their intrepid son had escaped from a train, and traveled across country to join up with his old unit? On November 30, 1864, Tod Carter was still with his unit when General Hood decided to launch an attack against entrenched Federal forces in Franklin. The large frontal assault was launched against the center of the Union line, which happened to stretch across the land owned by Tod’s father, Fountain Branch Carter. Tod was part of what has been called the Pickett’s Charge of the West. Legend has it that as the 20th Tennessee approached the Union lines dug across the Carter family property, Tod shouted to his comrades, “I’m almost home! Come with me boys!” Only 525 feet from the home in which he grew up, Tod Carter was hit by 9 bullets and lay in the family’s garden severely wounded. After the battle, as the Union troops moved northward toward the safety of the Union garrison at Nashville, Confederate soldiers sought out Fountain Branch Carter to inform him that Tod had been engaged in the battle and had fallen on the family’s property. Tod was brought home and laid in a bedroom just across the hall from the room in which he was born. After a journey of hundreds of miles that stretched to Ohio, Georgia and back to little Franklin, Tennessee, Tod Carter died in the comfort of his family’s bullet ridden home on December 2, 1864 at the age of 24. References Capt. Tod Carter’s Tragic Death, A Life Lost Too Soon Captain Tod Carter

There are two subtitles for this book: the one printed on the cover (The Amazing, Terrible and Totally True Story of the Civil War) and the one that should have been (Everything your schoolbooks didn’t tell you about the Civil War). Since author Steven Sheinkin was a text book author in a former life, he has the authority to proclaim his book is “History with the good bits put back!”

The two miserable presidents referred to by the title are Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis. The judgment of their misery does not refer to their job performance but to their extreme unhappiness. These two presidents are mentioned a couple of times throughout the book, and have a chapter dedicated to them, but they are not the focus. Instead, Sheinkin begins with writing a cogent summary of the causes of the Civil War and then proceeds to provide a chronological review of the years of the Civil War. Never getting too bogged down in details about any one battle or campaign, Sheinkin is able to keep the action moving while at the same time providing depth through quotes and stories from participants. The chapter dedicated to the soldiers' lives (Johnny Reb vs. Billy Yank) includes a story of Bob McIntosh and his half haircut, the common discussions soldiers had around the campfires (sweethearts and food) and the phenomenon of trading items across the lines between the rank and file soldiers on either side. There were a few minor errors (Joe Johnston was referred to as Joe Johnson; Chancellorsville was a lodging house, not a town; and John Wilkes Booth was a Marylander, not a Virginian). More importantly, there were a few errors of questionable history. Sheinkin says that after Gettysburg and Vicksburg “the South would never again be strong enough to invade the North.” That was 1863, but then also briefly recounts Jubal Early’s Maryland invasion of 1864 (yet another invasion of the north that occurred after Gettysburg). Recent scholarship has questioned the old story that Gettysburg began over shoes. Unfortunately Sheinkin’s citation is the wonderfully written, but not footnoted Civil War: A Narrative by Shelby Foote. It is a great story that highlights the absurdities of the Civil War. Unfortunately, the evidence that it happened is sketchy at best. Overall, this is a great book for the target age group, but don’t feel bad if the parents enjoy it, too. All age groups can benefit from this fun and quick read that is a great overview of the Civil War.  Today is May 3rd, and I can’t let the day pass without mentioning one of my very favorite places to visit-- a listing limestone marker in a family plot on a quiet corner of the Wilderness Battlefield. Here lies Stonewall Jackson. Well a part of him. Probably. On May 2, 1863, General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson led an audacious 12 mile march to surprise the Union troops on the Army of the Potomac’s right flank. The attack crumbled the Union line and blue troops ran in a disorganized retreat several miles before finally stopping and reforming nearer the crossroads lodging house known as Chancellorsville. Stonewall was famous for his aggression, and the night of May 2nd was no exception. To follow up his rout of the Union right flank, he considered a night attack. First, however, he needed to reconnoiter the enemy position. This he did, without bothering to tell his troops of his intentions. While Jackson, General Ambrose Powell Hill and members of Jackson’s staff moved forward, a brigade of North Carolinians moved in behind the party. Suddenly, without his knowledge, Jackson was caught in No Man’s Land. On his way back to his lines, the North Carolinians, waiting in the gloom of the Wilderness, near enough to the enemy to hear them digging, the darkness close around them, mistook the approaching mounted party as Union cavalry. Though Jackson’s party told the Confederate soldiers they were friends, the North Carolinians didn’t believe them and opened fire. Jackson was hit three times--once in his right hand, twice in his left arm. The Union troops responded to the Confederate volley with canister fire from the cannons positioned on the nearby roads. Jackson was dropped several times while his comrades attempted to evacuate him under heavy antipersonnel artillery fire. Jackson was taken to a field hospital near Wilderness Tavern where his arm was amputated. Amputation was quick and common in the Civil War as the soft lead ammunition used by both sides deformed on contact, tumbling through flesh and shattering bones. Usually, amputated limbs were piled high outside the field hospital, but Jackson’s chaplain, Reverend Beverly Tucker Lacy, took the arm to his brother's house at nearby Ellwood and the family buried the arm in the family cemetery. Jackson was taken to a farm about a dozen miles south of the battlefield near a railroad stop called Guinea Station. It was here in a small two room farm office on May 10, 1863 that he succumbed to pneumonia and died. Jackson was taken back to his beloved Lexington, VA. The arm was never reunited with the rest of Stonewall’s body.

|

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed