|

Drummer Boy just finished his fourth week of “home school” since Indiana’s school buildings closed down in mid-March, a closure that has since been extended to the end of the academic year. I truly appreciate Drummer Boy’s teachers, as they were able to put together the first two weeks of physical packets with about 48 hours of notice. In a rural school district where not everyone has internet or the technology to access it, they continue to work to keep kids connected and mentally active. Their lessons, however, are not intended to take the entire day (a fact that this particular work from home mother truly appreciates). The focus on math, reading and grammar only takes an hour or two, which means that the rest of the day is a vacuum waiting to be filled. There has been ample Lego building, baseball throwing, independent reading and more screen time than appropriate. Over the course of the last several weeks, however, a lot of organizations and companies have been putting together resources to help kids and their parents fill in that time with fun educational activities. Drummer Boy has been using several of them and, because he is my son, most of those activities have been Civil War history-related with one notable exception. If you have a student at home who would enjoy some supplemental Civil War history, or if you suddenly find yourself with time on your hands and you wish to learn a little Civil War history yourself, check out some of these great (and free) online resources and check back here regularly for Civil War Scout’s very own educational content.  The American Battlefield Trust The American Battlefield Trust was originally started as the Civil War Preservation Trust, and dedicated to leveraging private donations and government grants to purchase land that played an important role in the more than 3,000 Civil War battles that were fought across the country. Doing so allowed the public to experience the most important primary source from the Civil War: the land. The Trust’s new name came with an expansion of its focus and it is now preserving land from the American Revolution and the War of 1812 in addition to the Civil War, but its director of History and Education, Garry Adelman, is a bonafide Civil War geek. Their website has a lot of great resources for students and adults alike, but beginners may want to start here: Civil War Crash Course (choose how much time you have—from 15 minutes to a full week--and it will customize a curriculum for you) IN4 Minutes (over 100 short videos about a variety of topics including battles, personalities, technology and even a pronunciation guide to commonly mispronounced Civil War names and places)  National Park Service Junior Ranger Programs Most of the nation’s national parks have Junior Ranger programs to engage kids in fun and educational activities that help them understand the uniqueness of each park better. While these programs are intended to be completed (or at least started) while at the park and often include activities that require watching the park’s movie, visiting the displays in the Visitor’s Center and being in nature, several parks have made their booklets available online and once completed are offering to issue badges through the mail. Among these are:

National Park Ranger Programs

The rangers who work at our national historical parks and battlefields are true historians and have access to vast documents and artifacts that are not available for general viewing. During normal times, these rangers satisfy their educational charter by creating and delivering a wide variety of ranger programs to groups of visitors, young and old alike. With the current restrictions closing many parks entirely and enforcing social distancing where park trails and open spaces remain open mean these rangers no longer have eager groups of history geeks, students and tourists to lead around the battlefields. But for some of them, this is just a challenge, not a road block, and they are using Facebook to bring their parks and their expertise to virtual visitors everywhere. Several parks host Facebook Live videos, but don’t worry if you can’t make it when they go live…the videos will be hosted on their Facebook page and can be accessed as your schedule allows. Check out these parks’ Facebook pages for great distance learning opportunities:

Have I missed any great Civil War educational resources you want to share? Make sure to comment below!

0 Comments

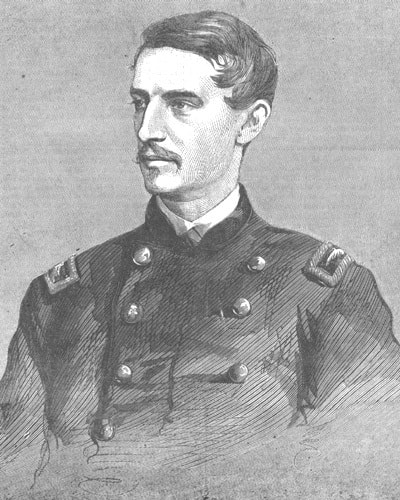

It was nearly incomprehensible that the Union's most successful spy, a women Ulysses S. Grant proclaimed had sent him “the most valuable information received from Richmond during the war,” was one of their own. Elizabeth Van Lew was not a northerner who moved to Richmond to become a secret agent for the Union. Nor was she born north of the Mason-Dixon, brought at a young age to live in Virginia. No, Elizabeth Van Lew was born a Richomonder, lived a Richmonder and died a Richmonder, ferociously loyal to the Virginia of the founding—a Virginia that was instrumental in the forming of the Union and all the prosperity that came from it. In fact, historian, author and University of Virginia professor Elizabeth Varon said that Van Lew believed “Virginia's distinct and special role as the architect of the Union required it to do whatever it could to preserve and sustain the county.” To say she was disappointed with the vote Virginia held on April 17, 1861 to secede from the Union, is likely an understatement, and it was compounded by the despair that followed when that decision was ratified by the populace of Virginia on May 23 by overwhelming numbers. Her career as a spy started by trying to help the Union prisoners of war kept in slum-like conditions in Libby Prison, a former tobacco warehouse that had been converted to a prison. The Confederate government was not inclined to use its scarce resources on the enemy, so food and medical care was minimal. Van Lew, first rebuffed by the prison's overseer, David H. Todd (Mary Todd Lincoln's half-brother), eventually convinced General John Winder to allow her in to see the Union prisoners by claiming she was only doing her Christian duty to be merciful to those least worthy of mercy. She brought food to supplement their meager diets, blankets and bedrolls, books, and in exchange often found out information. It was the beginning of a spy ring that would be responsible for assisting the daring escapees of the Libby Prison Break (of the 109 Union POWs to escape, 59 reached the safety of the north), and the exhumation and reburial of the body of Union Colonel Ulric Dahlgren, who had died in a raid on Richmond in March 1864 and was buried without honors in an unmarked grave because of his thwarted mission (most historians now believe the authenticity of the papers Dahlgren carried, which indicated Dahlgren's mission upon freeing Union POWs from Richmond's prisons was to execute members of the civilian Confederate government including Jefferson Davis himself, though some still believe the papers were planted to indict the Union in the eyes of the public, especially the those watching in England).  Union Colonel Ulrich Dahlgren was buried in an unmarked grave without military honors after a failed raid aimed at releasing prisoners and killing high ranking Confederate officials including President Jefferson Davis. Elizabeth Van Lew was instrumental in exhuming his body and reinterring it for his family. By the time the Union army had settled into its siege around Petersburg, just 24 miles south of Richmond, Van Lew was in contact with General Grant daily. When Richmond finally fell to Union forces on April 3, 1865 and her home was being threatened by the citizens of Richmond, she continued her compassionate care by treating the wounds of the civilians of Richmond, regardless of their loyalties.

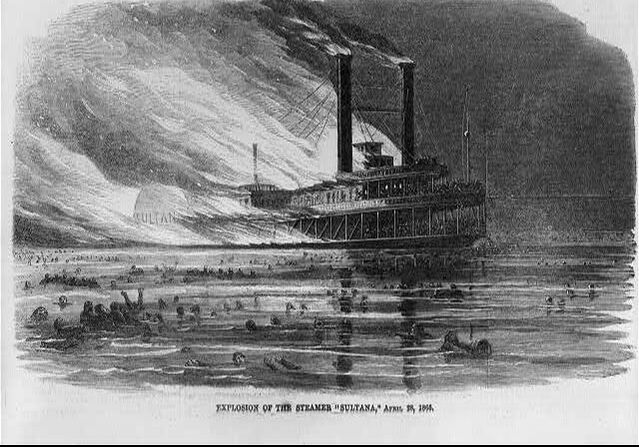

The money that the Van Lew family had spent to ease the sufferings of Union POWs and run the Richmond spy ring was never fully compensated by the Federal government. She would be granted the prestigious and lucrative post as the Postmaster of Richmond by President Grant in recognition of her loyalty during the war. Besides being prestigious and lucrative, the position of Postmaster was extremely political, and Van Lew found herself the target of political conspiring and was only able to hold the post until 1877 despite her abilities and success at the position. Sporadic employment followed, but in September 1900, Elizabeth Van Lew would die destitute at her Richmond home, despised by her Richmond neighbors and largely forgotten by the country she gave all to save. It was nothing short of miraculous that they had survived this long. Many of their comrades had not. Their time in the notorious Camp Sumter in Andersonville, Georgia and Cahaba Prison near Selma, Alabama had made them ill and emaciated. They kept holding on for one more day. Then word came that Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865 and the end of the war became inevitable. And these Union prisoners of war were soon issued their paroles and sent to a parole camp on the outskirts of Vicksburg, Mississippi to await transportation home to recover, to the extent they could, in the welcoming arms of their loved ones. On April 26, the paddle wheeler Sultana pulled in to Vicksburg to have her boilers checked out. A leak had necessitated diversion. She was on the way north on her regular run from New Orleans to St. Louis and only had 70 paying civilian passengers and 85 crew. The Union army was paying private boat owners for transporting troops north--$2.75 per enlisted man and $8 per officer. The Sultana’s captain wanted to capitalize on the potentially lucrative contract, but to do so, he’d have to push the limits of his boat. The Sultana was originally designed to hold 376 people, but due to both intentional forces (kickbacks and corruption) and unintentional forces (miscounting the number of rail cars bringing soldiers from the parole camp to the docks), over 2,000 men walked the gangway and crowded onto every available space. In the early morning hours of April 27, shortly after making a stop in Memphis, Tennessee, the Sultana was steaming north in the middle of the wide, flooded Mississippi River when the ship’s boilers, which had been hastily patched against the recommendation of the Vicksburg boilermaker who had tended them, suffered a catastrophic failure. The boilers exploded, the ship caught on fire and the decks and smokestacks collapsed. J. Walter Elliot described the scene: “…mangled, scalded human forms heaped and piled amid the burning debris on the lower deck. The cabin, roof, and texas were cut in twain; the broken planks on either side of the break projecting downward, meeting the raging flames and lifting them to the upper decks.” (Chester D. Berry, Loss of the Sultana and Reminiscences of Survivors, Lansing, 1892, pg. 115-117)

William A. McFarland observed, “The wildest confusion followed. Some sprang into the river at once, others were killed and I could hear the groans of the dying above the roar of the flames…I was on the hurricane deck aft. This part of the boat was jammed with men. I saw the pilot house and hundreds of them sink through the roof into the flames; at which juncture I sprang overboard into the river.” (ibid pg 249) For the men who weren’t scalded by the steam, burned by the fire, crushed by the collapse or crippled from their ordeal in the prisoner of war camps, their only chance at survival was to face the raging, swollen river. “The water around the vessel for a distance of twenty to forty feet was a solid, seething mass of humanity, clinging one to another. The best or luckiest man was on top. I then, after partially dressing, went forward, climbing down on the wreckage to the lower deck on the west side, and when I looked out over the water where but a few minutes before there were hundreds of men struggling for supremacy, now there were but few to be seen. The great mass of them had gone down, clinging to each other.” -- Sgt. James H. Kimberlin (J.H. Kimberlin, The Destruction of the Sultana, Hamilton, 1910, pg. 19) Some men paddled to shore using any buoyant object they could find. Some spent the night clinging to the limbs of trees whose trunks were awash by the river that had jumped its banks. Some were rescued by ships sent from Memphis. Though an accurate count of the victims of the disaster is not available, Jerry O. Potter, in his book The Sultana Tragedy: America’s Greatest Maritime Disaster, contends that the official death toll of 1,547 was likely understated by almost 300. Even so, the official death toll makes the sinking of the Sultana America’s greatest maritime disaster--outpacing the sinking of the Titanic (estimated at 1,517). The captain went down with the ship. Three Union officers who had a hand in overloading the ship all escaped military justice. In the end, no one was held accountable for one of the Civil War's saddest incidents.

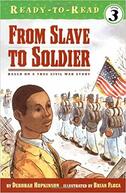

Young Johnny loves his mule, Nell, and his Uncle Silas but hates being a slave. When presented with an opportunity to join the passing Union army, Johnny leaves the plantation and joins up. Though he likes being free, and is treated well by his fellow soldiers, Johnny misses Nell and Uncle Silas. His sadness is eventually lessened when he is asked to help a soldier take care of the mule team used to drive a supply wagon. Johnny is given an opportunity to show his new comrades how competent he is and, in the process, his bravery earns him a Union uniform.

The story is based on the memoirs of John McCline who ran away from his Tennessee plantation in 1862 to join up with the 13th Michigan Volunteer Infantry and who became a teamster for the regiment. McCline’s memoirs were published in 1998. This is a great, age appropriate introduction to a topic of African American self-liberation. There were approximately 179,000 former slaves and freedmen in the United States Colored Troops (USCT) and their role in fighting for their emancipation is often times overlooked in the greater discussion of Presidential and Abolitionist influence in the Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th Amendment. Children can begin to understand the iniquity of slavery through two age-appropriate concepts: sadness at separation and the lack of appreciation he receives for his hard work. Parents will recognize strong will and understand the need of children to be given an opportunity to prove themselves. Hopkinson focuses on Johnny’s sadness at the separation from those he loves most in the world—Nell and Uncle Silas. Johnny’s mother is “gone” and there is no indication why. She may have been sold, or she may have died or run away (though Johnny’s initial reluctance to do so himself probably means it wasn’t the latter). The separation of families was one of the primary themes of abolitionist literature, including Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and is a concept that children can understand, probably better than concepts of freedom and owning the fruits of your own labor. The theme also allows families to discuss why Johnny’s freedom doesn’t alleviate his sadness, and why sometimes in life, people can feel conflicting emotions. Children may also be able to relate to needing to hear praise for a job well-done, something that Johnny doesn’t get on the plantation but does receive from his fellow soldiers after he delivers supplies. As a parent with an elementary school student, Johnny’s insistence that he can do it (drive the wagon) on his own, resonates with me and is a nice reminder that while I parent, it is important to allow children the opportunity to prove they can, in fact, do important things on their own. The narrative is helped along by excellent, but subtle, illustrations by Brian Floca. Though the text is very gentle on the institution of slavery, the illustration accompanying Johnny’s tale of being beaten for a runaway cow is powerful in its understatement. The overseer beating a figure is so small and inconspicuous, it implies this happens regularly and is not an extraordinary event that requires attention. Hopkinson and Floca’s work is a great way to address important topics of slavery and freedom in an age-appropriate and relatable way. Dubious history and preschoolers are a dangerous combination. I found this out as Drummer Boy and I sat next to my parents in a horse-drawn carriage, slowly wending our way through the narrow streets of Charleston, South Carolina. The end of the tour was drawing near, and I was already on the driver’s nerves for correctly answering his trivia question about the familial relationship between George Washington and Robert E. Lee, and had been silently shaking my head over his assertion that Washington D.C. had the country’s largest slave market (though D. C. did have slave markets, that particular “honor” belonged to New Orleans). Then came his words about the fighting out on Morris Island. “You would know that as the location of Fort Wagner. That battle was featured in the movie Glory. That was the first time black troops were in battle in the Civil War.”

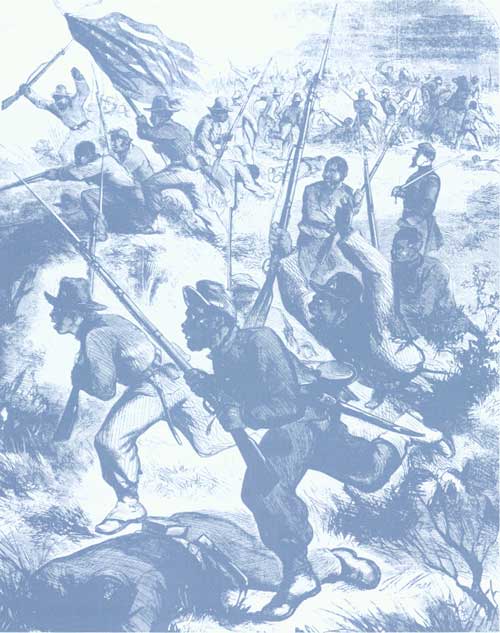

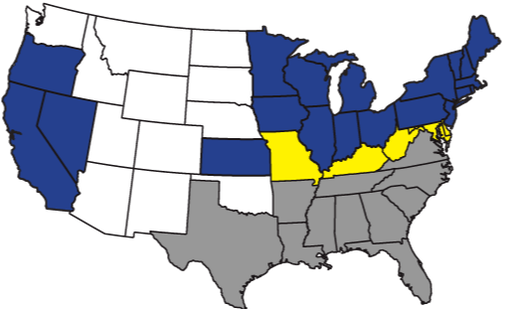

Only two rows back from the driver, I muttered, “That’s not true.” Drummer Boy, whose volume tends to range from loud to “screaming banshee” doesn’t know what sotto voce means, and couldn’t approximate it if required. So his response, “What’s not true, Mommy?” was clearly heard by our driver. I didn’t explain what his error was...he seemed disinclined to hear that he was 2 months and 800 miles off. That isn’t to say that the 54th Massachusetts doesn’t have an important place in American history. But rather than the first, new wave of a movement that would eventually see over 179,000 African Americans in Union blue, it was the final battle during the summer of 1863 that proved that African Americans would fight for their freedom. The Second Confiscation Act, passed in 1862, first opened the door for African American soldiers when it proclaimed in Section 11: “And be it further enacted, That the President of the United States is authorized to employ as many persons of African descent as he may deem necessary and proper for the suppression of this rebellion, and for this purpose he may organize and use them in such manner as he may judge best for the public welfare.” This language didn’t specifically refer to enlisting African Americans--freeborn or fugitive slaves--in the army. But it did set the groundwork for the use of black men in the war effort. For reticent Northerners and some in the administration, the idea of using blacks for fatigue duty—chopping wood and digging ditches--wasn’t an abhorrent one. They could appreciate the idea of blacks laboring for the cause of Union, but many still believed manual labor was all that blacks were good for. They doubted that black soldiers would stand up under enemy fire, leaving their white comrades vulnerable in battle. There were still those voices in the North when Abraham Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. This final version of the Emancipation Proclamation included something that the two previous drafts—the very first draft which Lincoln read to his cabinet on July 22, 1862 and the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation written on September 22, 1862—didn’t. “And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations and other places and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.” And with a stroke of a pen, African Americans in areas of rebellion would not only be “then, thenceforth and forever free”, but would also be accepted into the United States Army. At first, the African American regiments were raised to do the duty specifically laid out in the Emancipation Proclamation. These duties were previously provided by white soldiers, and their replacement by the black units would free up veteran white units to fight on the front line. Even now, however, there were plenty of northern civilians and politicians who believed that black men would not make good soldiers. In May 1863, Union forces surrounded the final two Confederate strong holds on the Mississippi River. Vicksburg, Mississippi was invested by troops under Ulysses S. Grant. 130 miles further south, Port Hudson, Louisiana was surrounded by troops under Union General Nathaniel P. Banks. Among the troops with General Banks were two regiments on the verge of making history. The 1st Louisiana Native Guard was originally formed as a response to Louisiana Governor Thomas Moore’s call to form militia companies upon the secession of the state from the Union. 1,500 free black men initially joined the 1st Louisiana Native Guard when its muster roles were opened on April 22, 1861. The governor accepted them into service with the Louisiana state militia. The unit was disbanded when the Confederate government refused to accept the unit into its service (the Confederate States of America would not enlist black men into its army until March 1865). After the fall of New Orleans to Union forces in April 1862, General Benjamin Butler located his headquarters there and began recruiting efforts. Once the Second Confiscation Act passed on July 17, 1862, he reached out to the city’s large population of freedmen and to the slaves escaping to Union lines, both groups of which could now serve the Union. Ten percent of the enlistees of the former 1st Louisiana Native Guard joined this new Union regiment. The regiment was even allowed black line officers. They were mustered in on September 27, 1862. The 3rd Louisiana Native Guard was similarly mustered into service in November 24, 1862 (its designation was changed to the Corps d’Afrique on June 6, 1863). After the departure of General Butler for eastern pastures, General Banks arrived in Louisiana. In general, Banks did not support the use of black troops and the presence of black line officers was even more concerning to him. He attempted to remove black line officers and replace them with white commanders, but in the case of the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guard, he largely failed. The night of May 26, 1863, the night before Banks’ planned attack on the fort at Port Hudson, the men of the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guard took up their position and prepared to commence the attack in the morning. As the sun rose, the difficulties of the attack were revealed. The ground had not been reconnoitered and as the troops surveyed the fort and its surroundings, they saw the Confederates had chosen the location wisely. The Native Guard would have to cross a pontoon bridge and advance on the fort under a high bluff lined with Confederate sharpshooters. Swamps and brush lining the road made it impossible to dislodge the Confederates from the bluff. There was no relief at the end of the road either, as the fort they were advancing toward sat high upon another bluff where more Confederate infantry men waited, along with the big artillery. There were people up north who thought that if these troops came under fire, they would drop their guns and run, but instead, the regiments advanced three separate times and were repulsed each time. The Native Guards did not break through the Confederate defenses. As they made their final retreat, the two regiments left nearly 200 men behind--dead, wounded or missing—including Captain Andre Cailloux who lost the use of an arm after being hit early in the battle but refused to leave the field. It was a fateful decision. Cailloux was hit by an artillery shell just before the final retreat. The injury was fatal. Though their attack was not a success in the military sense, the tenacity of the Native Guard did serve a greater purpose. The men of the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guard defied expectations by standing and fighting as well as their white comrades and in doing so, they began to roll back the tide of public opinion that saw them as no more than paid labor. After the attack, General Banks wrote his superior, General Henry Halleck, "The severe test to which they were subjected and the determined manner in which they encountered the enemy, leaves upon my mind no doubt of their ultimate success." Only ten days later, more black regiments would get to prove their mettle at a small supply base in Louisiana called Millikens Bend. Over the past several years the discussion about Confederate memory has been in the headlines, especially in regards to monuments. Discussions have taken place on college campuses, in high school board meetings, and at museums. Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and Nathan Bedford Forrest have all taken a figurative, if not literal, tumble from their pedestals. I've heard a lot of varied opinions, and (because I can't help myself, even though I should) Facebook and Yahoo comments about the appropriateness of the moves by local communities to “rewrite” the history of their public spaces. Often one of the most common responses I hear goes something like what I had as dinner conversation with a former business professor at a state university in Oregon, when he was discussing what he knew about his ancestors who had fought in the Civil War: “My grandfather who fought for the south, for Virginia, did it because he considered Virginia his country, like everyone did back then.” He voices a popular, if inaccurate, absolute: in the 1860s the state was paramount and people were more attached to their state than the concept of a federal government. The next logical step, then is that men and women of the time had no choice, that their fate was inexorably tied to the fate of their states. Whether intentional or not, what that statement does is separate the people from their decisions, making the onus for their support of the Confederacy someone else’s problem—namely the state legislators and secession delegates who voted to leave the Union. If there are no decisions to make, a person can't be judged. The myth that everyone just followed their state allows us to draw a clean line of demarcation between North and South and color large swaths of the map blue and grey. But if you've learned nothing from Civil War Scout in this last couple of years, I hope you can take this away...there is nothing simple about the Civil War. Men and women of the time did have choices…even the Confederacy’s most venerated generals. Robert E. Lee could have chosen to stay loyal to the Union. Historian Allen Guelzo makes an argument that his choice to follow Virginia was at least party driven by the desire to retain as much of his children’s birthright in the form of Arlington as he could (The Decision, Civil War Monitor, Volume 8, Issue 2). Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was born in the western counties of Virginia, that believing their voices were not heard in the secession vote, threw in with the Union and created the state of West Virginia. To say that it all was fate based on where a person was born or where they lived minimizes those who chose differently and suffered great personal consequences.  Union General George Thomas was born into a slaveholding family in Virginia. Union General George Thomas was born into a slaveholding family in Virginia. George Thomas was born a Virginian into a slaveholding family and when he stayed loyal to the Union his family disowned him. He rose to become one of the western army’s most reliable generals, and earned the nickname “Rock of Chickamauga” for his actions at that same battle that beat back the Confederate army’s attempt to overrun the retreating Union army. Even after the war, his family refused to speak to him ever again.

Look for more information about George Thomas, Clement Vallandigham and others who went against their state in a new series called Not a Monolith which will appear periodically on this blog.

In the pre-dawn hours of July 30, 1864, the Union army surrounding the city of Petersburg Virginia, ignited three fuses in a mine. The flames travelled toward two galleries packed with over 8,000 pounds of black powder. It was their hope that by blowing a hole in the Confederate lines and taking the heights behind it, they could capture the Army of Northern Virginia and end the war. It didn’t go quite as planned.

Alan Axelrod chronicles the series of events that turned this ambitious plan from one with bright promise to one of confused failure. There were active decisions made, to be sure, that doomed the action, but Axelrod shows how the abdication of responsibility for making decisions was a major factor in the plan’s failure. Beginning with the decision to simply allow the digging of the mine to alleviate boredom instead of fully endorsing or rejecting the plan, Generals Ulysses Grant and George Meade abdicated command responsibility. When his commanding officers forced him to choose different—untrained—troops to spearhead the attack only hours before the battle commenced, General Ambrose Burnside abdicated his responsibility to make a decision on whom the new leader and the new lead Division would be, instead leaving the choice of both entirely to chance (drawing straws). And when the time for attack happened, General James Ledlie, the commander who had won (or lost) the draw, sent his troops forward while he sat in a bomb-proof (bomb shelter) drinking rum, abdicating responsibility for leading his men into battle. Axelrod relies heavily on the War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (the ORs for short) and the testimony from the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Yet he weaves direct quotations from these sources into a highly readable narrative. The author does draw conclusions in his writing, but when he does it is clearly speculation and often he presents multiple possible conclusions. There is plenty of blame to go around, and Axelrod is fair in his assessment. Burnside’s perpetual need to be liked impacted his communications and may have driven the abdication of his authority. Meade’s trust in Burnside was impacted by the pair’s prior history, which wasn’t positive. Major Duane, Meade’s Chief Engineer, may have sandbagged the project because of ego, believing Colonel Henry Pleasants could not do something that Duane himself couldn’t do. General Grant is shown to be timid in his support and admitted that had Burnside been allowed to use the troops he wished, he believed the action would have been successful. James Ledlie was a drunk. At just under 250 pages, this is a page turner that includes technological innovations, compelling (if not necessarily likable) personalities, a vivid description of the horrors of war (particularly Chapter 10 Put in the Dead Men) and a very straightforward look at the red tape and bureaucracy of Civil War army leadership. Don’t be surprised if you feel frustrated as the story unfolds. The only thing this book suffers from is a lack maps. While it includes dozens of photos set within the body of the text, a map or two of the general location of the units and of the defensive trenches the soldiers fought in would have been helpful. Amtrak's City of New Orleans near Byram, MS. CC by Schnitzel_bank, some rights reserved. Railroads played a pivotal part in the Civil War. In 1861, as war erupted, the Union was crisscrossed by a vast railroad network that accounted for 22,000 miles of iron rail. The Confederacy added another 9,500 miles. The governments of both sides relied on railroads to transport men and material vast distances. This reliance on railroads to serve the logistical needs of the men in the field meant that rail centers and crossroads were prime targets for the armies. Manassas, Corinth, Chattanooga, Atlanta and Petersburg were all battles solely or largely because of the railroads that passed through them. It is surprising, then, that this self-styled Civil War and rail geek (yes, as a matter of fact, I am a blast at parties), didn’t make frequent use of Amtrak when planning my many battlefield explorations. I admit that the rail fan in me has been dormant for a while, but thanks to our family trip in April 2017 to chase the Norfolk & Western J-Class steam engine 611 and seeing Drummer Boy’s reaction to my own rolling, steaming moment of nostalgia, my love of rail travel has been revived. I was primed, therefore, to hear Willie Nelson’s version of The City of New Orleans while waiting at the deli counter of the local IGA and think, Wait…can I make a rail trip work for my vacation to Vicksburg? I mentally listed all the things that needed to fall into place—a long list, indeed—to set appropriate expectations. To my delight, I ended up checking off every box and within 3 weeks, found myself comfortably ensconced in a roomette on the southbound City of New Orleans headed to Vicksburg, via Jackson, Mississippi. This is not the first time I have taken the train to explore Civil War battlefields. Before this, my most recent trip on Amtrak was in 2008, when I first explored three now very familiar battlefields: Harpers Ferry, Antietam and Gettysburg. Considering that there are more than a dozen cities with significant ties to the Civil War served directly by Amtrak and another five which are accessible within an hour’s drive (and from stations that have nearby rental car availability), it is likely this won’t be my last foray either. Are you ready to ride the rails but not sure where you want to go? Check out these great Civil War destinations for your family’s next history by rail adventure! Direct Routes

Don’t Miss: Georgia Aquarium, College Football Hall of Fame and Six Flags Over Georgia Recommended Reading: War Like the Thunderbolt: The Battle and Burning of Atlanta by Russell S. Bonds; Stealing the General by Russell S. Bond Richmond, VA Served By: Northeast Regional, Carolinian, Silver Star, Silver Meteor, Palmetto Civil War Pedigree: The second capital of the Confederate States of America, Richmond, was a perpetual target of the Union army. The battles of the Seven Days in 1862 brought the fighting of the Penninsular Campaign to Richmond’s doorstep. The final push of the 1864 Overland Campaign reached the outskirts of Richmond as well. The city fell to Union forces on April 3, 1865. Civil War Related Sites: Tredegar Iron Works (NPS Visitor’s Center), American Civil War Museum, Hollywood Cemetery, Museum & White House of the Confederacy, Cold Harbor Battlefield, Gaines Mill Battlefield, Chickahominy Bluff Battlefield, Chimborazo Medical Museum, Glendale Battlefield, Fort Harrison, Drewry’s Bluff Battlefield, Malvern Hill Battlefield, Totopotomy Creek Battlefield Don’t Miss: Richmond Children’s Museum and Belle Isle Recommended Reading: To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign by Stephen Sears

Civil War Related Sites: Fort Sumter, Fort Moultrie, Warren G. Lasch Conservation Center (home of the Confederate submarine, the HL Hunley). Don’t Miss: The beaches of Folly Beach and Isle of Palms and the City Market Recommended Reading: Allegience: Fort Sumter, Charleston and the Beginning of the Civil War by David Detzer; Jack the Cat That Went to War by Russell Horres New Orleans, LA Served By: Crescent, City of New Orleans, Sunset Limited Civil War Pedigree: New Orleans was the largest city in the Confederacy. While it was under Confederate control, New Orleans served as an important naval town, building ships and submarines. In April 1862, Union ships, under the command of Admiral David Farragut, began a bombardment of the two forts protecting New Orleans downriver--Forts Jackson and St. Phillip. After seven days of close fighting, the majority of the Union fleet was able to pass by the forts and sail into capture New Orleans. The city would remain in Union hands throughout the duration of the war. Civil War Related Sites: Confederate Memorial Hall Museum, Fort Jackson, Metairie Cemetery, Fort Pike State Historic Site Don’t Miss: St. Charles Street Car, National WWII Museum, and Mardi Gras World Recommended Reading: When the Devil Came Down to Dixie: Ben Butler in New Orleans by Chester G. Hearn

Civil War Related Sites: The old Armory, John Brown’s Fort, the Stone Fort and Maryland Heights hikes, the artillery positions on School House Ridge and Bolivar Heights. Don’t Miss: Harpers Ferry Toy Train Museum and Joy Line Railroad, the view from the Maryland Heights overlook and Harpers Ferry Adventure Center Recommended Reading: Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War by Tony Horowitz Special Note: There is no rental car service in Harpers Ferry and limited lodging. If you wish to expand your horizons beyond Maryland, Loudon and Bolivar Heights (the ridges that ring the city), you may opt to get off Amtrak one stop to the west in Martinsburg, WV which has rental car access and lodging options nearby. Fredericksburg, VA Served By: Northeast Regional, Carolinian, Silver Meteor Civil War Pedigree: Owing to its location almost exactly halfway between the capital cities of Washington, D.C. and Richmond, VA, Fredericksburg and the surrounding area saw action in four large scale battles and several smaller ones. The battle of Fredericksburg (1862) was a thrashing of the Union army, and the battle of Chancellorsville (1863) is considered one of Lee’s greatest victories, but his success came with the loss of his most trusted lieutenant, General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. The Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House were the first two battles in the brutal Overland Campaign of 1864. Civil War Related Sites: Chatham Manor, Fredericksburg-Spotsylvania National Military Park (all four of the battlefields are included here with two visitors centers—one located in Fredericksburg and the other at the Chancellorsville battlefield), Stonewall Jackson Shrine, Mine Run Battlefield Don’t Miss: Carriage rides downtown Fredericksburg, Rappahannock Railroad Museum, Ferry Farm (George Washington’s boyhood home), Children's Museum of Richmond-Fredericksburg Recommended Reading: Simply Murder: The Battle of Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862, by Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White, Chancellorsville by Stephen Sears, A Season of Slaughter: The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, May 8-21, 1864 by Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White Manassas, VA Served By: Cardinal, Crescent, Northeast Regional Civil War Pedigree: Manassas Junction was the site of the important junction of the Orange and Alexandria Railroad and Manasasas Gap Railroad. The location of this vital rail juncture was only 30 miles outside of Washington D.C. The first Battle of Bull Run (July 1861) was a small affair with far reaching repercussions as the Confederates sent the Federals running all the way back to Washington. A little over a year later, the armies returned (August 1862). The scale was greater, but the results were similar. The Confederates prevailed on their way to Maryland and, they hoped, points beyond. Civil War Related Sites: Manassas National Military Park, Ball’s Bluff Battlefield Regional Park Don’t Miss: Bull Run Winery and the Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum Recommended Reading: Donnybrook: The Battle of Bull Run, 1861 by David Detzer Savannah, GA Served By: Palmetto, Silver Star, Silver Meteor Civil War Pedigree: Fort Pulaski, on Cockspur Island in the Savannah River, had served as a crucial link in the coastal defenses since its completion in 1847. After Georgia’s secession from the Union, 110 Georgians boarded a steamship bound downriver and seized the fort from the two Union caretakers guarding it. In December 1861, Union troops occupied Tybee Island, across the Savannah River from Fort Pulaski. After a 112 day siege, Union forces on Tybee Island asked for the surrender of Fort Pulaski on April 10, 1862. When the Confederates refused, an artillery bombardment ensued, and a surrender of the fort followed 30 days later. In 1864, Savannah was the objective of Sherman’s March to the Sea and was captured by Union troops on December 21, 1864. Civil War Related Sites: Fort Pulaski, Old Fort Jackson. Don’t Miss: Historic District, Pinpoint Heritage Museum, riverboat cruise Recommended Reading: Lee in the Lowcountry: Defending Charleston and Savannah in 1861-1862 by Daniel J. Crooks, Jr.

Civil War Related Sites: Petersburg National Battlefield, Pamplin Historical Park, Poplar Grove National Cemetery Don’t Miss: Pocahontas Island Black History Museum, US Army Quartermasters Museum, US Army Women's Museum Recommended Reading: The Horrid Pit by Alan Axelrod Springfield, IL Served By: Lincoln Service, Texas Eagle Civil War Pedigree: Abraham Lincoln lived in Springfield for almost 23 years. Springfield is where he married Mary Todd, where he started his family, where he setup his law practice and where he established his social network. Abraham Lincoln considered Springfield his hometown. “Springfield is my home, and there, more than anywhere else, are my life-long friends,” Lincoln wrote in 1863. Civil War Related Sites: Lincoln Home National Historic Site, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum Don’t Miss: Knight’s Action Park and Caribbean Water Adventure, Henson Robinson Zoo Recommended Reading: Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln by Doris Kearns Goodwin, Lincoln's Gamble: The Tumultuous Six Months That Gave the United States the Emancipation Proclamation and Changed the Course of the Civil War by Todd Brewster, Who Was Abraham Lincoln? by Janet B. Pascal, Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved Books by Kay Winters and Nancy Carpenter

Civil War Related Sites: Ford's Theater (which, as a working theater, still stages plays and musicals throughout the year), Lincoln Memorial, Washington's Civil War Defenses, Arlington National Cemetery and Robert E Lee House. Don't Miss: National Archives, The Smithsonian (any of its many amazing museums), National Zoo Recommended Reading: The Quartermaster: Montgomery C. Meigs, Lincoln's General, Master Builder of the Union Army by Robert O'Harrow Memphis, TN Served By: City of New Orleans Civil War Pedigree: Memphis’ location on the Mississippi River meant that the city must be taken by the Union to realize their war goal of complete control of that river. On June 6, 1862, the Confederate “cotton clad” naval forces attempted to defend the city from the Union ironclad fleet. It was a clear Union victory, which virtually destroyed the Confederate inland navy. The victory opened the river as far south as Vicksburg. Memphis was under Union control until the end of the war. Civil War Related Sites: Mississippi River Museum in Mud Island Park, Elmwood Cemetery Don’t Miss: National Civil Rights Museum, Graceland, Beale Street, Memphis Zoo Recommended Reading: Mr. Lincoln's Brown Water Navy: The Mississippi Squadron by Gary D. Joiner Staunton, VA Served By: Cardinal Civil War Pedigree: Staunton was at the crossroads of two major roads and the railroad, making it a communication and transportation center. Because of this location in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, it was the objective of several Union incursions up the Valley (in Valley parlance, “up the valley” is south, “down the valley” is north). Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and Richard S. Ewell both used the city as headquarters, and throughout the war, the city served as a army post, training camp and quartermaster post. The city was captured and occupied by Union General David Hunter, who sacked the town during the four days his troops were there. Civil War Related Sites: Staunton is a gateway to the Valley. Rent a car and drive north to see New Market, Cross Keys and Port Republic. Drive south to Lexington. Don’t Miss: American Shakespeare Center, Frontier Culture Museum, Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library and Museum Recommended Reading: Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson by S. C. Gwynne You could spend years riding the rails and checking out these destinations, but there's even more history just a hop, skip and a jump away from the train station. In part two of this series, we'll introduce you to even more Civil War destinations you can get to on Amtrak...including one way out New Mexico way. Yup, you read that right...New Mexico.

With all of the attention on Confederate monuments recently, I am happy that at least some of the discussion is around the idea that monuments are frequently inaccurate representations of the events they commemorate but faithful representations of the attitudes of those who built the monuments. What and how we, as a society, choose to commemorate says less about the nobility and honor of the acts and people we are remembering and more about what we find noble and honorable and memorable in those acts and people. Values change as society changes, and our commemorative landscape can act as a time capsule showing us exactly what society deemed important at the moment that the memorial was built. When I went to Gettysburg so I could photograph some of the beautiful commemorative artwork on park grounds, I never anticipated such a clear cut example of this in a small, unobtrusive state monument tucked near where the tour road begins its ascent of Culp’s Hill. Some people who have been following the Confederate monument debate may be surprised, even, that this perfect example of what so many historians have been saying about commemoration and memory is actually a Union monument. I am a Hoosier born and raised, so this is not the first time I have seen the Indiana State Monument. It is the first time, however, I took a close look at the monument. Nearly 13 feet high, the monument features two granite pillars, labeled Liberty and Equality. The central panel features a carved relief of the State Seal of Indiana over the words: Dedicated to those Hoosiers who so nobly advanced freedom on this great battlefield. On the left panel, underneath the Liberty pillar, are the words: In honored memory of those valiant men of Indiana who served in the: 7th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; 14th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; 19th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; 20th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; 27th Ind. Vol. Inf. Regt.; I & K Companies 1st Ind. Vol. Cav. Regt.; ABCDEF Companies 3rd Ind. Vol. Cav. Regt. On the right panel, under the Equality pillar, are the words: On July 1, 1863, Indiana units engaged Confederate forces at Gettysburg and sustained some of the first casualties among the Union ranks. In this battle to preserve the Union, 552 men from Indiana were casualties to that cause. The monument itself sits upon a patio of Indiana limestone and is flanked by two benches where visitors may rest and reflect. There is something on this monument that very specifically dates its creation. Can you find it? To help you, let’s take a closer look at the words used on this monument. The description of the action for the Indiana regiments is an accurate depiction of the battle. The 19th Indiana was one of the five “western” regiments that made up the Iron Brigade, the first Union infantry troops on the battlefield on July 1st. The brigade’s losses were heavy and Gettysburg was essentially the last time that the Iron Brigade was the fearsome, aggressive fighting force that had won its nickname at the Battle of South Mountain in September 1862. The short dedication focuses on advancing freedom with success on the battlefield. After the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863, Washington, D.C.’s war goals were expanded from simply union to union and emancipation. Lincoln echoed the idea of freedom through victory in battle in November of 1863 in his immortal Gettysburg Address. Liberty is defined as the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one’s way of life, behavior or political view. Liberty is one of the key concepts of the Declaration of Independence, the underlying framework for Lincoln’s speech. Equality is mentioned in the Declaration of Independence, too, however, it is a concept relatively anachronistic in the Civil War. Certainly, the words “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” are included by Lincoln in his monumental speech. However, the historical record shows that even in the north, where slavery was outlawed by state constitutions, emancipation did not equal racial equality. This is certainly true in Indiana, where the second version of Indiana’s Constitution, passed in 1851, included Article XIII: Negroes and Mulattoes with the following provisions:

Though Article XIII was removed in 1881, Hoosier soldiers fighting at Gettysburg came from a state that, despite outlawing slavery, was not interested in establishing equality for black freedmen and freedwomen.

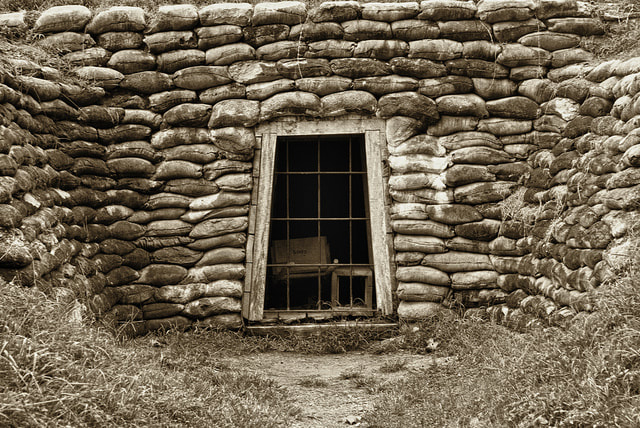

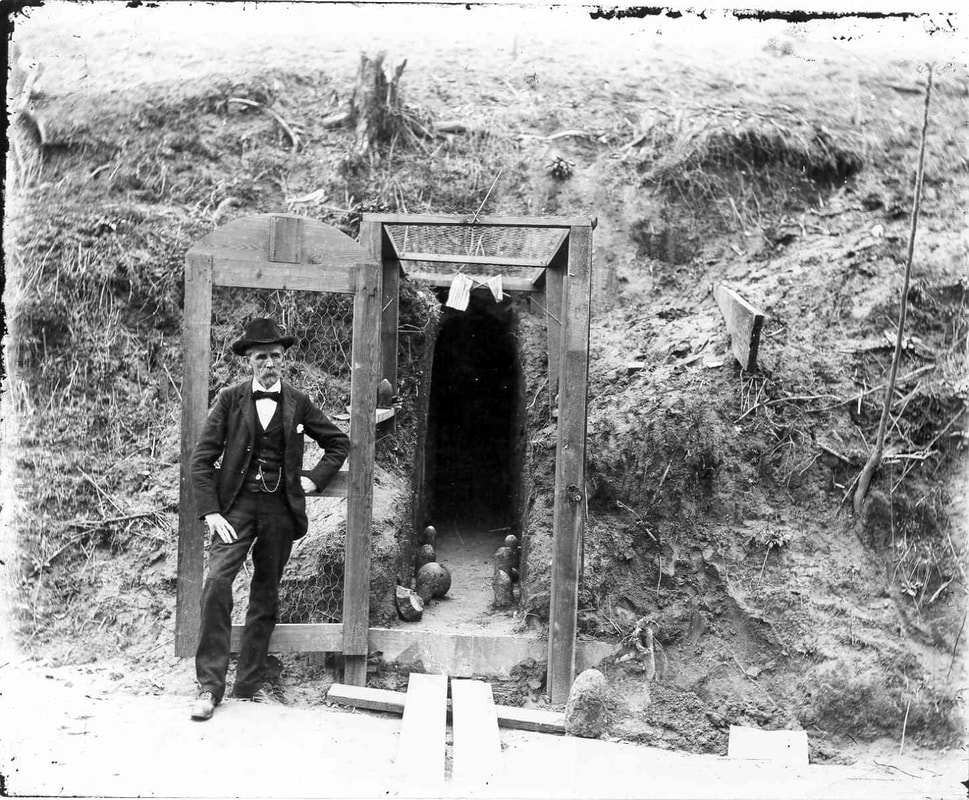

The inclusion of the term “equality” however, does give us an idea of when this monument was created. Google N Gram can show us when terms associated with “equality” began to appear in print. The non-qualified word “equality” has been more popular than either “racial equality” or “negro equality”, but the first two terms had notable increases in usage in the 1960s which corresponded to the Civil Rights movement. The term “equality” peaked in usage for the 217 year span beginning in 1800 and ending in 2017 in 1974. A monument designed and built in the immediate aftermath of that societal shift focusing on the attainment of equal rights for blacks, the removal of segregation, and the legal recognition and federal protection of the citizenship rights in the United States Constitution, would certainly look at the Civil War as the first step along the long, circuitous and halting journey toward the equality gained from the Civil Rights Movement. The Civil Rights Movement ended in 1968. The monument was built in 1970. The people of Mississippi had a hard decision to make. For more than a year, the Union forces had attempted to take the clifftop fortress of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River. For more than a year, they had failed. But on the night of April 16, 1863, the Union inland navy under the command of Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, ran the batteries of Vicksburg. As their attempt to sneak by the bluff top cannons under cover of darkness was discovered, the boats hugged the west bank of the river and kept moving as fast as their paddle wheels and the river current could carry them. Every one of the Union ships was hit and sustained damage, but all but one made it. Now, all of the river transports General Grant needed to move his troops from the west bank of the river to the soil of Mississippi were at his command. Soon, the entire Union Army of the Tennessee would be on the road to Vicksburg. The threat of an approaching enemy army forced the area’s citizens to a make a choice. They could stay where they were, far from the protection of the Confederate army and hope that the Union forces would pass them by. If they gambled wrong, they could be subject to humiliation and potential danger as the army moved toward its destination, extending foraging parties along and ahead of the army’s line of march, and trailing stragglers like detritus behind it. Or, they could abandon their property to the tender mercies of the enemy and seek the protection of the Confederate army in the one place they knew the army would be…Vicksburg. Many citizens chose the latter. A month later, after the Union army had defeated the Confederates at Port Gibson, Raymond, Jackson, Champion Hill and Big Black River Bridge, they finally arrived at Vicksburg. Many of the city’s civilians had stayed behind and were joined by those from smaller outlying towns, country farmers and plantation owners. On May 19th, Grant’s army attempted to fight its way into town. It failed. On May 22nd, it tried again. It failed. It was then apparent to Grant this his only option was to “out camp” the Confederates…and consequently all the civilians left within the “protective” embrace of the Confederate trenches. The safety the Mississippians had sought was illusory. The noose began to tighten. The siege had begun. Emma Balfour stayed behind with her husband, a popular physician in town. As the Union army began to surround Vicksburg on May 17, 1863, she was already expressing concern about the city’s fate. “What is to become of all the living things in this place when the boats commence shelling, God only knows. Shut up as in a trap, no ingress or egress, are thousands of women and children who fled here for safety. Then all the mules and horses belonging to this department—and all the stock of all kinds for fifteen or twenty miles around! The Dr. thinks human life will be endangered by the stampede amongst these creatures when terror seizes them. The only comfort is that we can live on them—for I fear we have not provender to feed them for long.” (EB 12-13) Mary Loughborough was one of those fleeing civilians Emma mentioned. On May 19th, as the Union troops attacked the Confederate positions in the trenches encircling Vicksburg, she remembered, “I did not regret my decision to remain, and would have left the town more reluctantly to-day than ever before, for we felt that now, indeed, the whole country was unsafe, and that our only hope of safety lay in Vicksburg. The food shortage both Emma and Mary feared would become real soon enough, but even before then there would be a new, and terrifying form of suffering—the Union gun boats were back. The citizens were stuck between a rock and a hard place. The Union army had formed a semicircular line of trenches anchored on the Mississippi River both north and south of the city. And on the river were gun boats whose cannons were trained on the defensive positions the Confederates held close to town. “At that moment, there was firing all around us, a complete circle from the fortifications above all around us to those below & from the river.” Mary Balfour and the other citizens in Vicksburg were surrounded. (EB 24). Once the guns and the gun boats opened fire, shells began to rain down on the streets of Vicksburg, destroying buildings and striking fear into the civilians—mostly women, children and slaves—who were left in town. People couldn’t sleep or walk outside for fear of a shell bursting and harming or killing them. “The room that I had so lately slept in had been struck by a fragment of a shell during the first night, and a large hole made in the ceiling. I shall never forget my extreme fear during the night, and my utter hopelessness of ever seeing the morning light.” (ML 56) The salvation that many sought would be found just beneath their feet. Vicksburg’s position in the Mississippi River delta country meant that the soil making up the bluffs was an uncommon wind-blown silt and sand mixture known as loess. The flat plate-like grains of this soil make it porous, but not permeable. It is light and soft, but incredibly stable. For the citizens of Vicksburg that meant one thing…caves. Soon after the siege began, the Vicksburg cave construction and real estate markets boomed. Free men and slaves hired out by their owners used shovels to excavate a variety of caves in the soft soil. Some were small and intended for a single family. Others were large and could accommodate several families in separate private quarters with common living spaces and hallways. Lida Lord Reed, the daughter a local minister, and a child of about 11 at the time, described her cave: “Our refuge consisted of five short passages running parallel into the hill, connected by another crossing them at right angles, all about five feet wide, and high enough for a man to stand upright…the people in our cave that night were not counted , but I have heard it stated since that including three wounded soldiers, there must have been at least sixty-five human beings under the clay roof.” (CM 923) Mary Loughborough moved her family into a cave, too. “Our new habitation was an excavation made in the earth, and branching six feet from the entrance, forming a cave in the shape of a T. In one of the wings my bed fitted; the other I used as a kind of a dressing room; in this the earth had been cut down a foot or two below the floor of the main cave; I could stand erect here; and when tired of sitting in other portions of my residence, I bowed myself into it, and stood impassively resting at full height.” (MB 61) The caves were hot, humid, and stinky. Bugs, snakes, and rodents were constant companions, and though many residents brought some comforts of home—furniture, rugs, books—the walls were still dirt, the candle light was dim, and the only privacy they could have in the communal caves was courtesy of blankets hung in dug out doorways. And yet it kept people safer than being above ground, and all for the bargain price of $30 to $50 (about $600 or $1,000 today). (ML 72) It kept people safer, but the cave dwellers were by no means safe. Lucy McRae, another young girl whose family moved into the caves shortly after the siege began, had a close call when a shell exploded directly overhead of her family’s cave. A large chunk of dirt was dislodged by the explosion, burying Lucy. Her mother and their neighbors were frantic, desperately digging with their hands to free the child. In her memoir, Lucy wrote, “The blood was gushing from my nose, eyes, ears and mouth. A physician who was then in the cave was called and said there were no bones broken, but he could not then tell what my internal injuries were.” Lucy would recover. Others would not. (DS 126) “Sitting in the cave, one evening, I heard the most heartrending screams and moans. I was told that a mother had taken a child into a cave about a hundred yards from us; and having laid it on its little bed, as the poor woman believed, in safety, she took her seat near the entrance of the cave. A mortar shell came rushing through the air, and fell with much force, entering the earth above the sleeping child—cutting through into the cave—oh! most horrible sight to the mother—crushing in the upper part of the little sleeping head, and taking away the young innocent life without a look or word of passing love to be treasured in the mother’s heart.” (ML 79-80) As the days wore on, the threat posed by artillery fire continued, and was joined by the prospect of hunger. As food became more scarce, the cave dwellers began to get desperate. Mules were slaughtered and rats were eaten. Even Lida Lord Reed’s beloved pony Cupid, who had accompanied the family to the caves, disappeared, likely a victim of hungry mouths. (CM 927) The civilians weren’t the only ones suffering. In fact, the civilians were arguably comfortable compared to Pemberton’s Confederates, who were now subsisting on quarter rations, enough to keep the nearly immobile army alive…barely. On June 28, Confederate General John Pemberton received a letter signed “Many Soldiers.” “ If you can’t feed us, you had better surrender us, horrible as the idea is, than suffer this noble army to disgrace themselves by desertion. I tell you plainly, men are not going to lie here and perish, if they do love their country dearly. Self-preservation is the first law of nature, and hunger will compel a man to do almost anything. Six days later, on Independence Day, General Pemberton surrendered the city of Vicksburg and his hungry army to General Ulysses S. Grant. The 47 day siege of Vicksburg was now over.

References CM--A Woman's Experiences during the Siege of Vicksburg by Lida Lord Reed The Century Magazine, April 1901, pp. 922-927 DS--The Most Glorious Forth: Vicksburg and Gettysburg, July 4th, 1863 by Duane Schultz. 2002 WW Norton and Company ML--My Cave Life In Vicksburg with Letters of Trial and Travel by Mary Loughborough. 1976 The Reprint Company EB--Mrs. Balfour’s Civil War Diary: A Personal Account of the Siege of Vicksburg by Emma Balfour. 2008 Edited and published by Gordon A Cotton |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed