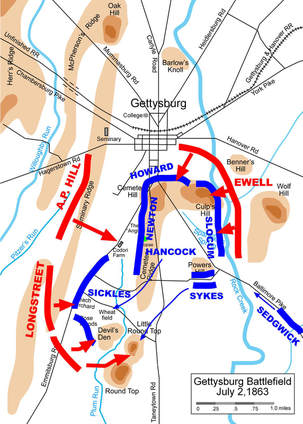

But just south of Gettysburg on the morning of July 2, 1863, the ghosts Union III Corps commander General Dan Sickles was seeing were Confederate cannoneers and their artillery pieces. Just two months prior, he had been holding high ground at Chancellorsville. To cover the hill, Hazel Grove, Sickles had to position his troops forward of the main line in a protrusion called a salient. Behind him, the ground sloped down to the house at the crossroads of the Orange Plank Road and Orange Turnpike that gave the battle its name. But as the battle unfolded on the May 3rd, Union army commander Joe Hooker lost his nerve and decided to consolidate his line in a defensive position around the intersection. That necessitated Sickles withdrawing his troops to the bottom of the hill, and leaving the heights to the Confederates, allowing them to rain artillery shots down on his Corps’ heads. So nearly two months later, on July 2, when Sickles was ordered to place his III Corps on the south end of Cemetery Ridge extending the left flank of the army from Hancock’s II Corps to Little Round Top, General Sickles looked out ahead of him about a mile to a ridge where he could see the trees of a peach orchard. And all of a sudden, he was seeing ghosts. He disliked his position here in the low saddle where Cemetery Ridge dwindled and disappeared before the ground sloped upward again on the flank of Little Round Top. If the Confederates could take the high ground to his front and open up cannons on his position, he would be dominated. He’d been through all that before, and it hadn’t ended will for him or his men. So he sent a request to army commander General George Meade and asked him if he could advance his corps to the high ground. Meade declined. Sickles tried again and this time, Meade sent General Henry Hunt, the Chief of Artillery of the Army of the Potomac, on an inspection and consultation with Sickles. Hunt generally agreed about the potential for artillery in the Peach Orchard, but he had concerns about the move, too. He agreed to take Sickles’ request to move forward to the high ground back to Meade.

But Sickles couldn’t or wouldn’t wait. Without orders, he advanced his corps forward. His right flank was anchored on the Codori Farm and the line bent back at an angle at the Peach Orchard to place its left flank at Devil’s Den. His line had gone from one mile long to two miles long...too long for his 12,000 men to adequately defend. It also left a gap in the Union line where he had pulled his troops forward. Sickles decided to plead his case one last time. By the time Meade arrived at Sickles’ salient, both men, neither of whom liked the other, were raring for a fight. In a fit of petulance, Sickles asked Meade if Meade wanted his men to return to their assigned position back on Cemetery Ridge. Under the first shells fired by the Confederates at this advanced position, Meade declined, gesturing toward the Confederate line. Those guys may have something to say about that. Mead started sending in reinforcements as support, but Sickles’ line was just too long and thin to appropriately defend the high ground, and as the Confederate infantry came out of the tree line of Warfield Ridge and began to move toward the Peach Orchard, Sickles’ men broke and, as General Hancock had predicted earlier in the day as Sickles moved his troops forward, the III Corps came “tumbling back” with Confederates in hot pursuit. By that time, however, Sickles has already left the field. He had been hit by an artillery shell which nearly amputated his leg. He was carried from the battlefield clenching a cigar in his teeth and industriously puffing away to silence the rumors of his death circulating among his soldiers. A Union surgeon completed the artillery shell’s work by removing the leg. His amputated leg was preserved at the Army Medical Museum Washington, D.C. where he would visit it often. For observant viewers, the leg makes a cameo in the 2012 film Lincoln. There is no statue to Sickles on the battlefield, though he was a corps commander at the time and instrumental in the establishment of Gettysburg National Military Park. Why? He believed his actions saved the day for the Union army and bombastically laid claim to grander memorials than a mere statue. He was known to say, “The whole battlefield is my monument.”

1 Comment

|

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed