Private James E. Staley, Band Company, 9th Indiana Volunteer Infantry. Liljenquist Family collection (Library of Congress) Private James E. Staley, Band Company, 9th Indiana Volunteer Infantry. Liljenquist Family collection (Library of Congress) Winter. Cold winter. On those kinds of days, when the cold and damp seem to seep into the bones, it’s nice to sit in front of a fireplace with a roaring fire, sipping a cup of hot cocoa. But on the night of December 30, 1862, as 83,000 soldiers dressed in blue and butternut were filing into the fields northwest of the Tennessee town of Murfreesboro, there was not going to be that kind of comfort. The distance that separated the men of the Union Army of the Cumberland and the Confederate Army of Tennessee as they went into bivouac that night was negligible. At some points on the line, only 300 feet separated the men of the opposing armies. Up and down both lines, veterans--men who had "seen the elephant"--understood that they were on the eve of a great attack. Union Brigadier General Henry M. Cist wrote, “Every soldier on that field knew when the sun went down on the 30th that on the following day he would be engaged in a struggle unto death, and the air was full of tokens that one of the most desperate of battles was to be fought.” Up and down the line the tension grew in anticipation of what was to happen when the sun next came up. And then, one of the regimental bands began to play. The calm, crisp night air allowed the tune to carry across the No Man’s Land between the armies, and all up and down the line, Union regimental bands would pay a song and Confederate regimental bands would answer. A rousing “Hail Columbia!” was countered by a rollicking “Bonnie Blue Flag.” “Dixie” would be answered by “Yankee Doodle.” Finally, one regimental band broke the cheerful competition and began to play the song “Home Sweet Home,” and regimental bands all over the field, Union and Confederate alike, picked up the refrain and soldiers, North and South, began to join their voices to the chorus of brass echoing “Be it ever so humble, there is no place like home.” No matter which side of the Mason-Dixon they were from, or what color uniform they wore, they shared a deep longing for the comforts of home and family. The camaraderie was short-lived. The Battle of Stones River began at dawn the next day and by battle’s end on the evening of January 2, 1863, 24,645 soldiers had been killed, wounded or were missing. Stones River would go down in history as the Civil War battle which had the highest percentage of those engaged become casualties...and for the remarkable experience that for a short time bonded enemies over the sweet strains of nostalgia played by regimental brass bands. Sources and Suggested Reading Battle of Stones River; The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture v. 2.0 God Rest Ye Merry, Soldiers: A True Civil War Christmas Story by James McIvor

0 Comments

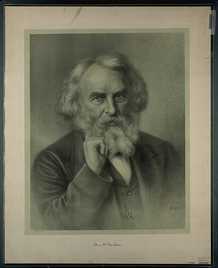

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Library of Congress Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Library of Congress All it was supposed to take to resolve the momentous issue of Secession and Union was one battle. Some people even believed that battle would amount to no more than bloodless posturing. North Carolina Congressman and avid secessionist A. W. Venable, offered “I will wipe up all the blood shed with a handkerchief of mine." It wouldn’t last long. It would be all over by Christmas. But as December 25, 1861 passed, neither side had folded like their opponents expected. And as the sun set on December 25, 1862, the war seemed like it would continue to consume good men on both sides. The war was not proving to be quick, nor was it over by Christmas. By the time Christmas 1863 arrived, the mood in the country was anything but celebratory. The message of joy, hope and peace threatened to be silenced by the turmoil of the war. The dual Union victories in Gettysburg and Vicksburg in the height of the previous summer that seemed to herald the beginning of the end had turned instead into familiar inaction in the East and a bitter Federal defeat at Chickamauga in the West. And all across the nation, families were dealing with the wounding and death of their loved ones. Among those experiencing their own personal tragedies amid the nation’s crisis was American patriot and poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. In 1861, his beloved wife of 18 years, Frances “Fanny” Appleton Longfellow, was tending to household chores when her dress caught fire and though Henry tried to smother the flames, he was unable to save her. Then, in March of 1863, Fanny and Henry’s oldest son, Charles, slipped away from home to visit Washington, D.C. to join the Union Army. While there, the seventeen year old ran into an old family friend, Captain W.H. McCartney of Battery A, 1st Massachusetts Artillery, and appealed to the Captain to enlist him. Unwilling to take an underage recruit without parental permission, Captain McCartney sought the approval of the boy’s father. The elder Longfellow reluctantly granted it. Charlie was a natural soldier, and was soon offered a commission as Second Lieutenant of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry. He still held this rank when, on November 27, 1863, Charlie was engaged at the Battle of New Hope Church (Mine Run Campaign) in Orange County, Virginia. He was shot through the left shoulder. The bullet traveled across his back, nicked his spine, and exited under his right shoulder. He escaped paralysis by a mere inch. When word got through to Henry of his eldest son’s serious injury, he and his younger son Earnest set off to Washington, D.C. to bring Charlie home to recover. It was in the midst of this personal and national tragedy that Longfellow heard the bells ringing from church belfries on Christmas morning 1863 and sat down to capture his raw emotions in words. The poem that he wrote that morning, Christmas Bells, was published in 1865 and later set to music to become a popular Christmas carol that speaks to the triumph of joy, hope and goodness even (or especially) during the disillusionment of the darkest times--I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day. I heard the bells on Christmas Day Their old, familiar carols play, and wild and sweet The words repeat Of peace on earth, good-will to men! And thought how, as the day had come, The belfries of all Christendom Had rolled along The unbroken song Of peace on earth, good-will to men! Till ringing, singing on its way, The world revolved from night to day, A voice, a chime, A chant sublime Of peace on earth, good-will to men! Then from each black, accursed mouth The cannon thundered in the South, And with the sound The carols drowned Of peace on earth, good-will to men! It was as if an earthquake rent The hearth-stones of a continent, And made forlorn The households born Of peace on earth, good-will to men! And in despair I bowed my head; "There is no peace on earth," I said; "For hate is strong, And mocks the song Of peace on earth, good-will to men!" Then pealed the bells more loud and deep: "God is not dead, nor doth He sleep; The Wrong shall fail, The Right prevail, With peace on earth, good-will to men.” |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed