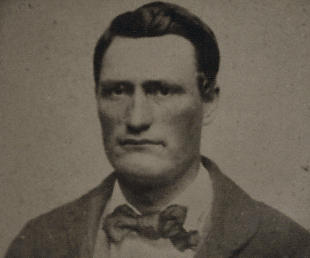

Amos Humiston, Photographer Unknown Amos Humiston, Photographer Unknown This time last year, social media was on the hunt for a man who was photographed dancing at a club. The caption of the photo posted on an internet message board indicated the overweight man had been ridiculed by his fellow club-goers and was embarrassed into stopping. It wasn’t long before the post went viral and the man, a Brit named Sean O’Brien, was identified and invited to a Hollywood dance party organized just for him. The incident showed the power of social media, the ability of a vast network of barely related people to search the globe to find people and bring them together. Sometimes it is hard to remember that this technology is still, in the grand scheme of things, very new. 150 years ago, as the Civil War raged across the country, no one could even imagine the capabilities we have today. Today, anonymity can be difficult. In 1863, it was a possibility that was all too real to the men who fought. In the midst of the Civil War, communication was still relatively primitive. No one was going to be able to post a photo of an anonymous soldier and broadcast it around the world seeking his identity. Because dog tags hadn’t been invented yet and most soldiers hadn’t gotten into the habit of pinning their names and units to their uniforms, many men faced the possibility that their final words and last breath would happen in anonymity, and their bodies would be committed to a final resting place without a name on their headstone. It may have been this fear that ran through Amos Humiston’s mind as he lie dying in a remote portion of the Gettysburg battlefield on July 1, 1863. He had been part of the 154th New York, and his regiment had been positioned on the northeast side of town as the battle commenced. As the Confederates bore down on the town, the 154th New York was overwhelmed and as their line gave way, the soldiers put up a fighting retreat through the streets. The firefight was intense and Amos Humiston was mortally wounded. We cannot know how long he suffered, but we do know that his death was not instantaneous. How? Later in the week, his body was found near the corner of York and Stratton Streets, with an ambrotype of his three children clutched in his hand. That ambrotype was the only identification on him. His unit suffered heavy casualties from the fight and those who survived had already moved on by the time his body was found. Without any identification and no one to vouch for him, his fate as a Unknown Soldier should have been sealed.

On October 19, 1863, a description of the photograph (photographs could not be reproduced in newspapers of the time) and the circumstances of the soldier’s death, appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer under the headline Whose Father Was He?

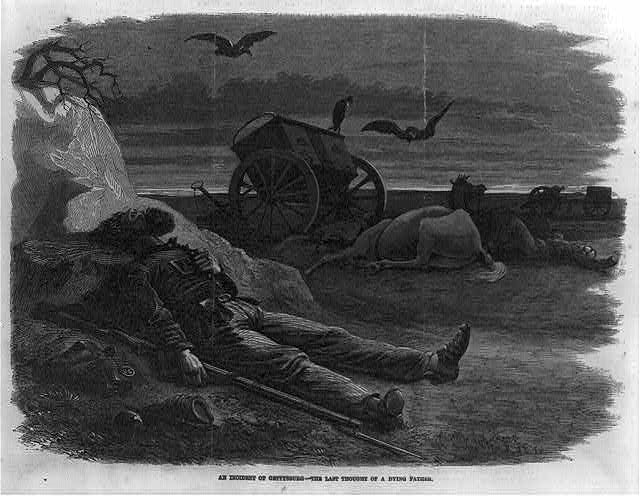

"After the battle of Gettysburg, a Union soldier was found in a secluded spot on the battlefield, where, wounded, he had laid himself down to die. In his hands, tightly clasped, was an ambrotype containing the portraits of three small children ... and as he silently gazed upon them his soul passed away. How touching! How solemn! ... It is earnestly desired that all papers in the country will draw attention to the discovery of this picture and its attendant circumstances, so that, if possible, the family of the dead hero may come into possession of it. Of what inestimable value will it be to these children, proving, as it does, that the last thought of their dying father was for them, and them only." Without a photo, the article had to be as descriptive as possible and included notations on clothes (the eldest boy was wearing a shirt of the same material as the girl’s dress), estimated ages (the 9, 7 and 5 were only a year off) and circumstance (the boy in the center is wearing a dark suit and sitting on a chair). Newspapers across the country picked up the story, and on October 29, 1863, Amos Humiston’s wife, Philinda, read this description in a church magazine called American Presbyterian while at her home in Portville, NY. She suspected the description was of her children Frank, Alice and Freddy, but wrote to Dr. Bourns to be sure. He sent her a copy of the ambrotype. When she opened the envelope, all doubt was removed. The anonymous soldier whose last vision before death were the children he loved, had been her husband, Amos Humiston. Amos is buried in Gettysburg National Cemetery. His headstone bears his name.

0 Comments

|

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed