If you proclaim an interest in the Civil War, there are a few books that it is assumed you have read. At the top of that list is Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass: An American Slave. One of the best known slave narratives, this autobiographical book packs a big punch in fewer than 100 pages.

At its most basic level, it tells the story of Frederick Douglass’s life in slavery and his escape from it. He details brutality at the hands of some masters and consideration at the hands of others. He tells about times of abundance and times of scarcity. He tells of the tasks he was set to do and those which he chose for himself, often, like his Sabbath School classes, in secret. If this was all that was in this book, it would be enough. But the book also contains a significant amount of subtext that challenges the status quo of Antebellum America. Douglass is a master story teller using classic literature and the Bible to deliver an abolitionist sermon, especially aimed at northern Christians who were turning a blind eye to slavery. In fact, one of the overriding themes of this work is that Christianity is an aggravating factor in slavery, not a mitigating one. The masters who most conspicuously proclaimed themselves Christians were the worst masters. Further, Douglass's subtitle to this work--An American Slave--was, I believe, an intentional choice meant to claim the sin of slavery for the entire nation. Everyone--northerners and southerners, slave holders and free-labor proponents, Christians and non-Christians alike--were complicit in slavery. No one's hands were clean. The impact slavery has on the enslaved is the central theme to many studies of the time, but in the person of Sophia Auld, Douglass illustrates the impact slavery has on the enslavers. When he first meets her, Douglass describes Sophia as “a woman of the kindest heart and finest feelings. She had never had a slave under her control previously to myself, and prior to her marriage she had been dependent upon her own industry for a living.” He claimed to be “astonished by her goodness.” Sophia taught Douglass the alphabet and the rudiments of reading. When her husband, Douglass’s master Hugh Auld, discovered this, he put an immediate stop to it. “If you give a n-- an inch, he will take an ell. A n-- should know nothing but to obey his master--to do as he is told to do. Learning would spoil the best n-- in the world. Now, if you teach that n-- how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanagable and of no value to his master. As to himself, it could do him no good, but a great deal of harm. It would make him discontented and unhappy.” Douglass notes that from that moment on, Sophia Auld began to lose those qualities--piety, warmth, charity and tenderness--that had so thrilled Douglass upon his first meeting her. Her heart grew hard. Douglass even acknowledges, “Slavery proved as injurious to her as it did to me.” Hugh Auld’s lecture to his wife also introduces another central theme: slavery was more than simply bondage of the body. It was bondage of the mind. Douglass understood from that moment on that education was the key to true freedom. Hugh Auld was right. Education would make him discontent and unhappy. Douglass would spend the rest of his childhood as a slave bartering what he could with local boys to get them to teach him to read. When he had nothing to barter, he would dupe those same boys into teaching him by issuing challenges he knew the boys couldn’t ignore. Once he knew how to read, he organized secret Sabbath Schools to help other slaves gain the education that had so discontented Douglass. The original Preface, written by William Lloyd Garrison, can be a barrier. Garrison wrote like someone who liked to hear himself talk. His writing is bombastic in the formal and rather overblown language of orators of the time, and Douglass’s clear and concise writing is a welcome read after the multipage Preface. There are many editions of this book. While the main body’s text will remain the same, some editions provide additional information that will help provide context and further understanding of this deceptively complex work. I read a 1993 edition edited by David Blight. Blight’s footnotes and the supplemental materials highlight the rich literature Douglass drew upon to write his autobiography, and give a glimpse into his subsequent public work. While this particular text is out of print, it can be found used on Amazon and abebooks.com.

0 Comments

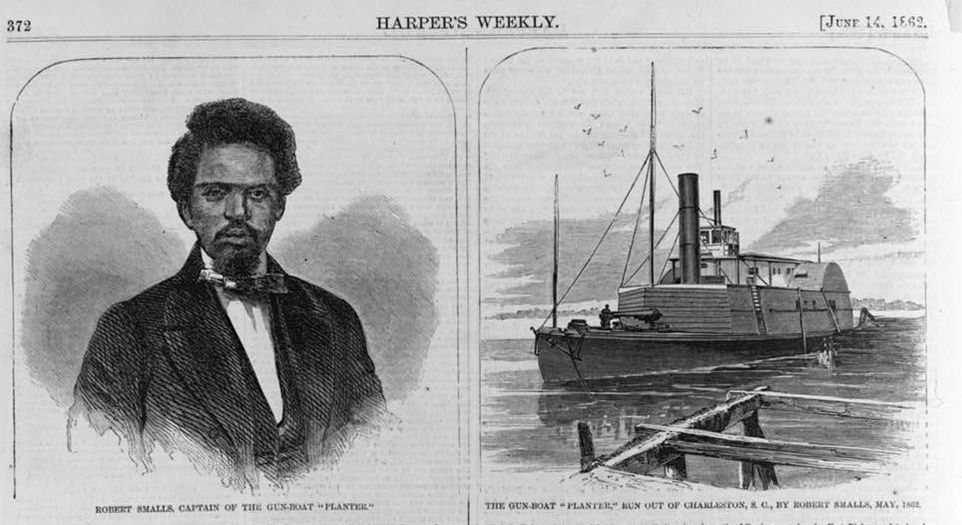

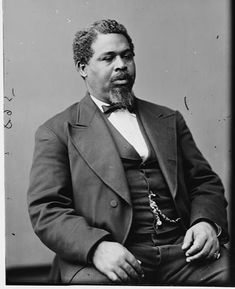

Robert Smalls was not a steamship pilot for the Confederacy. He was responsible for maneuvering the side wheel steamer, Planter, through the dangers of Charleston harbor to the relative safety of open water. Though those happened to be the same duties as a boat’s pilot, he was instead given the title of wheel man. Only white men could be pilots. The wages he earned were the property of the master who had hired him out. He was aiding the Confederate war effort by strengthening the defenses of Charleston Harbor. He helped lay torpedoes (mines) in the channels, destroyed a lighthouse, and brought supplies to the Charleston area forts. And he wanted the Union to win the war. When the sun fell on the evening of May 12, 1862, the three white crewmembers from the Planter defied Confederate regulations by leaving the boat for the evening. They trusted Smalls and the other slaves who remained on board. When it became evident that the Confederate sailors were not coming back that evening, Smalls shared with his fellow slaves a daring plan. Just before dawn, Smalls and a crew of eight, along with five women and three children-including Smalls' wife and children, eased the Planter from the dock. They knew their plan was daring and dangerous. If, at any point in the next few hours their plan failed, everyone agreed that they would blow up the boat. For them, it was freedom or death. Smalls wore the straw hat that the boat’s captain usually donned on his rounds, and convincingly mimicked the captain’s posture so well that in the uncertain pre-dawn light, no one from the forts questioned the boat or crew as they moved through the harbor, flashing all the correct secret signals so as not to attract attention. Once they were out of range of the forts' cannons, the South Carolina and Confederate flags were struck, and they ran up a white bed sheet that had been brought onboard by Smalls' wife. The Planter and its crew set their sights on the ships of the Union blockade. An eyewitness aboard the USS Onward, the nearest ship, described what happened next, ““Just as No. 3 port gun was being elevated, someone cried out, ‘I see something that looks like a white flag’; and true enough there was something flying on the steamer that would have been white by application of soap and water. As she neared us, we looked in vain for the face of a white man. When they discovered that we would not fire on them, there was a rush of contrabands out on her deck, some dancing, some singing, whistling, jumping; and others stood looking towards Fort Sumter, and muttering all sorts of maledictions against it, and ‘de heart of de Souf,’ generally. As the steamer came near, and under the stern of the Onward, one of the Colored men stepped forward, and taking off his hat, shouted, ‘Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!’ ”(James McPherson, The Negro's Civil War) Robert Smalls and his small band on the planter were slaves no longer. Though the Emancipation Proclamation had not been issued yet, Congress had already passed the First Confiscation Act permitting the confiscation of any property, including slaves, being used to support the Confederate war effort. They were free.

When I was sitting in the field at the Bloody Angle at Spotsylvania Court House in 2015, I saw two park-goers engaged in a game of soccer…on the remains of the trenches of the Mule Shoe Salient. When I asked that they not climb over the trenches where thousands of men fought for 20 hours in what may have been the most brutal combat of the Civil War, the gentleman of the couple asked me if I even knew what it was about. I laughed. He took it to mean I didn’t know.

In truth, I laughed because this topic comes up with alarming frequency on a very popular Civil War message board where I spend time. In late 2015 and early 2016, a poll asking members about the cause of the Civil War generated a measly 39 votes which then generated 3,170 posts (and counting) that totaled 159 pages long. So why is there still a controversy 150 years later about what caused the Civil War? I have been debating for some time exactly how I want to go about addressing what tends to be the enduring controversy of the Civil War: What was it all about, anyway? I really didn’t want to launch the site to immediate controversy because no matter how well I write about this particular topic, someone will be upset. But the truth is, the way others address this situation tells me how serious a scholar they are, and I should be willing to put my credentials on display for my loyal readers by addressing this particular issue to the best of my ability. Besides, to exclude the topic from my initial launch of the website buries one of the most essential and important things to be learned from the Civil War. If we don’t know why it was fought, how can anything else really matter? Check out my essay on The Cause of the Civil War on the Civil War Topics Page. |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed