|

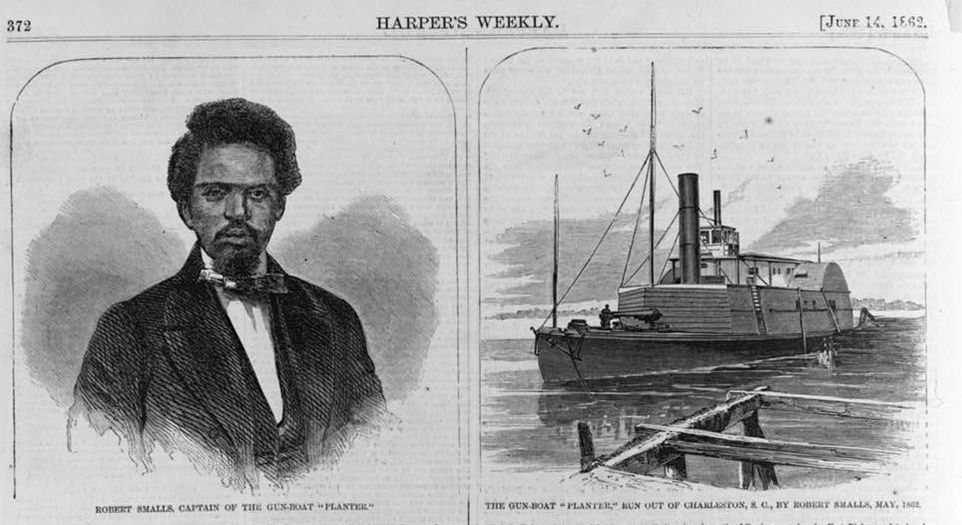

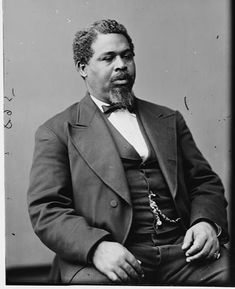

Robert Smalls was not a steamship pilot for the Confederacy. He was responsible for maneuvering the side wheel steamer, Planter, through the dangers of Charleston harbor to the relative safety of open water. Though those happened to be the same duties as a boat’s pilot, he was instead given the title of wheel man. Only white men could be pilots. The wages he earned were the property of the master who had hired him out. He was aiding the Confederate war effort by strengthening the defenses of Charleston Harbor. He helped lay torpedoes (mines) in the channels, destroyed a lighthouse, and brought supplies to the Charleston area forts. And he wanted the Union to win the war. When the sun fell on the evening of May 12, 1862, the three white crewmembers from the Planter defied Confederate regulations by leaving the boat for the evening. They trusted Smalls and the other slaves who remained on board. When it became evident that the Confederate sailors were not coming back that evening, Smalls shared with his fellow slaves a daring plan. Just before dawn, Smalls and a crew of eight, along with five women and three children-including Smalls' wife and children, eased the Planter from the dock. They knew their plan was daring and dangerous. If, at any point in the next few hours their plan failed, everyone agreed that they would blow up the boat. For them, it was freedom or death. Smalls wore the straw hat that the boat’s captain usually donned on his rounds, and convincingly mimicked the captain’s posture so well that in the uncertain pre-dawn light, no one from the forts questioned the boat or crew as they moved through the harbor, flashing all the correct secret signals so as not to attract attention. Once they were out of range of the forts' cannons, the South Carolina and Confederate flags were struck, and they ran up a white bed sheet that had been brought onboard by Smalls' wife. The Planter and its crew set their sights on the ships of the Union blockade. An eyewitness aboard the USS Onward, the nearest ship, described what happened next, ““Just as No. 3 port gun was being elevated, someone cried out, ‘I see something that looks like a white flag’; and true enough there was something flying on the steamer that would have been white by application of soap and water. As she neared us, we looked in vain for the face of a white man. When they discovered that we would not fire on them, there was a rush of contrabands out on her deck, some dancing, some singing, whistling, jumping; and others stood looking towards Fort Sumter, and muttering all sorts of maledictions against it, and ‘de heart of de Souf,’ generally. As the steamer came near, and under the stern of the Onward, one of the Colored men stepped forward, and taking off his hat, shouted, ‘Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!’ ”(James McPherson, The Negro's Civil War) Robert Smalls and his small band on the planter were slaves no longer. Though the Emancipation Proclamation had not been issued yet, Congress had already passed the First Confiscation Act permitting the confiscation of any property, including slaves, being used to support the Confederate war effort. They were free.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorToni is a wife, mom and history buff who loves bringing the Civil War to life for family members of all ages. Archives

July 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed